Close to half a million people die from malaria each year according to the World Health Organisation, and that number could rise due to growing resistance to pesticides. But one UK-based company is hoping to beat that with a two-barrel approach.

As governments, companies and private donations respond to The Global Fund's call to meet its 14 billion US target to continue its fight against HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria, innovations dependent on the funds have a chance to showcase their projects during these two days in Lyon.

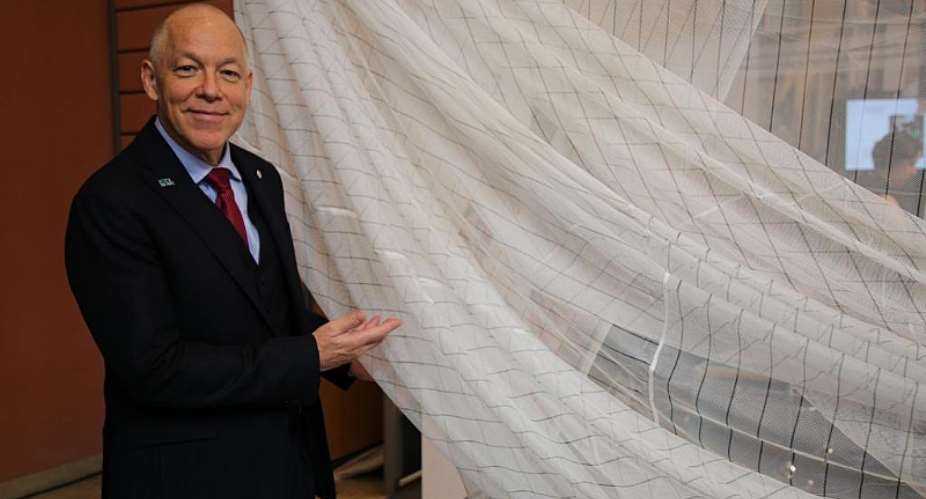

One in particular is a new approach to mosquito nets.

“Most mosquito nets have one insecticide in the, and this one has two, which means that the mosquito is hit from two different directions with two different modalities of operation and that's what makes the difference,” explains Michael Anderson, the CEO of MedAccess, a UK-based company that supports projects worldwide to “achieve global health goals.”

In conjunction with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and BASF, a German chemical company, MedAccess is supporting this mosquito net that took six years to develop adds Anderson.

Resistance to insecticide

The problem in eradicating malaria has been the very mosquitos that spread the disease. “The challenge for all of us, is managing as mosquitos evolve and they develop resistance to new techniques.”

That means the current net is not as powerful as before in killing the insects, although the net itself still remains a helpful barrier for those sleeping beneath it.

This product tries to address this problem by blending two active ingredients, making it “much harder for the mosquito to evolve in a way that will response to both active ingredients simultaneously,” explains the CEO.

It's easier for a mosquito to evolve and develop a resistance to one active ingredient, but two? It's much harder adds Anderson, noting “that's why we think this net is going to last for some time”.

The new ingredient, called Interceptor G2 has two classes of insecticide. One of them is pyrethroids, which is already used in nets, and the second is chlorfenapyr, one that is “widely used on crops, used for killing insects in households,” and has been in circulation since the 1960s says Anderson.

Wear and tear

Although nets have been proven to help block mosquitos access to humans, they inevitably break down and need to be replaced.

And that takes money.

“Most countries run a campaign every three years, it's a common pattern to replace all the nets every three years,” explains Anderson. “The nets are designed to be active after at least 20 washes, they're designed to be that durable.”

Which is why access to funds, in this case coming from The Global Fund, governments can support those big campaigns to replace the nets.

In areas where malaria is more prevalent, the climate is normally wetter and humid, a factor that could also contribute to a shorter life time of these new nets.

“They [the new nets] seem to have really good resilience. Of course these nets are new, they're on the market. They've been tested many times, and the testing shows really strong resilience. But we'll have to see in the field what actually happens.”

Cost of the net

Even if governments actively provide access to nets, there is still a cost. And in this case, the cost is inevitably higher.

“The partnership that we've had with BASF and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; the three of us have put together this package to bring down the prices of this new net, closer to the price of existing nets.” Anderson says that was a 40 percent drop from the original price, but it's not as inexpensive as the net with just one insecticide.

He adds that the key to bringing down the cases of malaria, particularly in West Africa is finding new methods of tackling mosquitos.

April 20: Cedi sells at GHS13.63 to $1, GHS13.06 on BoG interbank

April 20: Cedi sells at GHS13.63 to $1, GHS13.06 on BoG interbank

Dumsor: I'm very disappointed in you for messing up the energy sector — Kofi Asa...

Dumsor: I'm very disappointed in you for messing up the energy sector — Kofi Asa...

Dumsor: Instruct ECG MD to issue timetable and fire him for lying — Kofi Asare t...

Dumsor: Instruct ECG MD to issue timetable and fire him for lying — Kofi Asare t...

Ashanti region: Road Minister cuts sod for 24km Pakyi No.2 to Antoakrom road con...

Ashanti region: Road Minister cuts sod for 24km Pakyi No.2 to Antoakrom road con...

Train crash: ‘How could any normal person leave a car on rail tracks?’ — Frankli...

Train crash: ‘How could any normal person leave a car on rail tracks?’ — Frankli...

Train crash: Driver of abandoned vehicle not our branch chairman nor secretary —...

Train crash: Driver of abandoned vehicle not our branch chairman nor secretary —...

Kenya pays military homage to army chief killed in copter crash

Kenya pays military homage to army chief killed in copter crash

US agrees to pull troops from key drone host Niger: officials

US agrees to pull troops from key drone host Niger: officials

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...