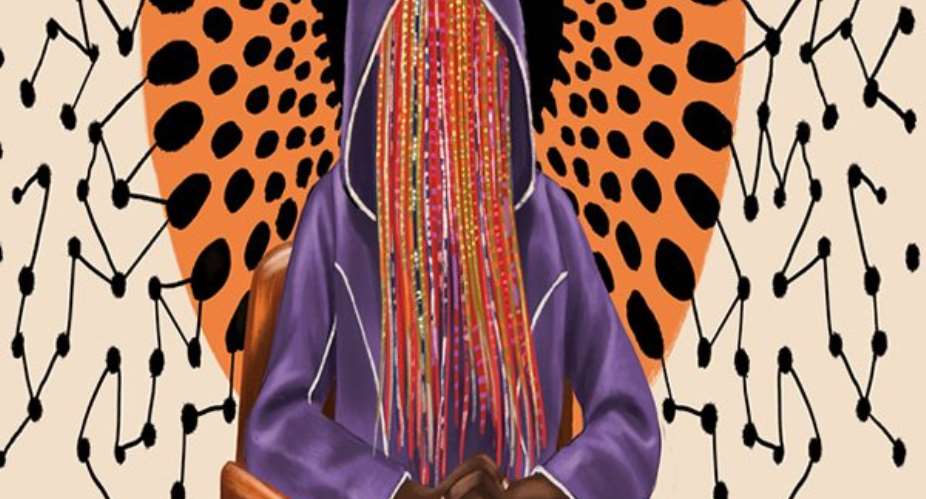

Closed Curtain: Anas Aremeyaw Anas at the funeral ceremony of Ahmed Hussein-Suale, whose killing was likely a retaliation for his Tiger Eye reporting. Francis Kokoroko / Reuters Pictures.

Number 12 was first screened on June 6, 2018, at the Accra International Conference Centre. The audience reacted in shock, anger, and grief as they took in the corruption orchestrating matches between their favorite club teams. The finished documentary, an extraordinarily complex and broad story line with a cast of characters spanning the continent, stretched nearly two hours. (A 50-minute behind-the-scenes version was produced for the BBC.) It exposed referees and officials from 15 countries who accepted bribes in exchange for fixing club and international matches in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Morocco, and beyond. The investigation went almost to the top of the African soccer hierarchy, taking down Kwesi Nyantakyi, who was the president of the Ghana Football Association (GFA), the vice president of the Confederation of African Football, and a FIFA Council member, and who in the past had promised to reward anyone who came forward with evidence of corruption in the GFA.

“Since he premiered his documentary, football is on its knees in Ghana,” Darko, Anas’s lawyer, told me. The GFA was thrown into turmoil and, until the launch of a special series of matches in March, the nearly 40,000 gleaming yellow and red plastic seats in the Accra Sports Stadium remained mostly empty. Of the more than 70 Ghanaian referees who were alleged to have accepted bribes, 51 were banned from soccer-related activities, 8 of them for life. Nyantakyi resigned from his position; he was arrested and questioned by police, but released on bail soon after. FIFA banned him from all soccer activities. Nearly a year later, however, Nyantakyi has not been formally charged in Ghana. Anas recently launched a petition to pressure the attorney general’s office to proceed with criminal prosecution.

In the documentary, a Tiger Eye investigator meets with Nyantakyi under the pretext of seeking to sponsor the Ghana Premier League. Nyantakyi negotiates a commission for a proposed deal of $50 million, lining up his own savings and loan company as a broker. Hidden cameras capture him accepting a wad of cash—allegedly $65,000—offered by the undercover investigator as a token of thanks. Nyantakyi also promises the investigator access to lucrative contracts in Ghana if he agrees to make a series of offers totaling $11 million to a number of the country’s government officials, including the president and vice president. The implication of bribery of a sitting executive was explosive. Up until Number 12 , Anas’s investigations had never touched politics—he’s careful to declare nonpartisanship. (Ghana’s president and vice president were interviewed for the film, and both categorically denied knowledge of Nyantakyi’s plan.)

Tiger Eye’s cameras also captured Nyantakyi singling out one man in particular for any side deals: Agyapong, the ruling-party MP. “He is very loud,” Nyantakyi says on the tape. Agyapong does indeed have a reputation for being loud. He has a history of making public accusations and name-calling his adversaries, and he is also loud in the literal sense—when he makes television and radio appearances he sometimes roars into the microphone with such force that the speakers crunch. (In 2016, Asante, the Citi FM journalist, wrote an exasperated blog post titled “For God’s sake, shut up, Kennedy Agyapong.”) During the frenzied lead-up to the Number 12 premiere, as details of the exposé became public, Agyapong issued his call for violence against Hussein-Suale. He also delivered a long tirade against Anas, questioning his credentials and the legality of his methods and calling him an “evil extortionist blackmailer.” A few weeks later, Agyapong aired his own documentary, Who Watches the Watchman .

Agyapong’s criticisms are the fiercest (and loudest) ever leveled against Anas, and they have found an audience. “At first Anas had a halo,” Asante told me. But now “there are actually journalists who are split between the MP who is claiming Anas is corrupt, and people on Anas’s side.” She falls squarely in the latter camp, dismissing Agyapong’s accusations as a self-defensive tactic to deflect attention from his own corruption. She expressed admiration for what Anas had accomplished. Whether or not you agreed with his methods, she said, “every sports journalist knew the GFA’s president was corrupt. But there was no documentary proof. Nobody was willing to put their life on the line for that.”

Anas’s influence on Ghanaian culture may rival his influence on the country’s public institutions. He has become a household name, shorthand for standing up to corruption and exploitation. The rappers Obrafour and Opanka have paid him tribute in music videos, and last year the fashion designer Elikem Kumordzie launched a line of Anas-inspired clothing, complete with his-and-hers draped fabric masks. In Accra I spotted stickers with his bucket-hat-and-beads silhouette, which has become instantly recognizable, warning that ANAS IS WATCHING. Asante laughed when I asked her about that phrase.

“People will threaten you with Anas now,” she said. “My colleague tells a really funny story that somebody called him and said, ‘You know this water connection problem you have? If you paid me money I could make the bills go away.’ He said, ‘I was tempted, but then I thought, What if it’s Anas?’ So he was like, ‘I just went to the water company and did the right thing.’ ”

Around Accra you can find murals of Anas painted by the artist Nicholas Wayo; one of the largest stretches across the front gates of a school in Nima. The scene depicts a line of people with their faces covered by beads—a judge, a police officer, a doctor, a soldier—over the words SAY NO TO CORRUPTION. Next to them is Anas in a bucket hat, with the words DO THE RIGHT THING. Wayo told me that he wants to continue his mural on an adjacent wall reading JOURNALISM IS NOT A CRIME, but that some school administrators have been wary of political themes since Number 12 came out.

There’s a local term for the Anas phenomenon in media and academic circles: Anasism. Audrey Gadzekpo, a journalist and the dean of the School of Information and Communication Studies at the University of Ghana, hosted a daylong seminar on Anasism last year, after the release of Number 12 . A panel of experts critically examined Anas’s work and undercover methodology through the lens of the law, philosophy, journalistic ethics, and political science. The seminar was not hero worship; Anas himself attended and responded directly to critics of his work. Gadzekpo, for her part, had disagreed with the way Agyapong attacked Anas, but she considered some of his complaints to be valid, including on the issue of privacy.

“You see now, it is the citizens who are doing the journalism for you. They are the ones going on the street and filming the police harassing them.”

Anas has been sued by the subjects of his investigations, for breach of privacy and defamation. “We jokingly say there is no journalist in Ghana who has been sued more than Anas Aremeyaw Anas,” Darko said. Ghana’s legal code and the Ghana Journalists Association code of ethics is clear: if privacy is breached, or deceitful or indirect means used to obtain information, an exemption is made so long as that information is in the interest of the public good. Public interest, Darko explained, always overrides individual interest, and so far this has protected Anas from prosecution. Though he has been sued all the way to Ghana’s Supreme Court, Darko told me, Anas has yet to lose a case.

Anas has also been accused of entrapment: luring people to take bribes and then springing allegations of corruption on them. Kove-Seyram dismisses this out of hand. People in public office, or military uniform, or a referee’s uniform, all know in the clearest terms that accepting cash or gifts is a violation of the rules, he says. In footage he reviewed from the Number 12 investigation, more than one official refused the money they were offered.

Illustration by Shyama Golden

Gadzekpo also brought up concerns around the blurring of lines between Anas’s public-interest investigative journalism and his PI company, which is limited liability with shareholding directors. What happens, she wondered aloud, if an investigation for a private client conflicts with public-interest reporting? “It’s kind of like a media organization being sustained by a conglomerate; your independence will be compromised if you have to do a story that affects the bottom line of the conglomerate that owns you.”

I had this question for Anas, too, when we met on the rooftop: Who holds him accountable? He chuckled softly from behind his beads, and responded, “My critics.” Rumors of his power, he said, have been greatly exaggerated—though he gets a kick out of hearing them. “When they say I’m Illuminati,” he said, laughing, “I feel like a cool Illuminati guy walking around.” There are rumors that he can disappear at will, or shape-shift into animals, or that he’s a spirit. I heard a rumor that “Anas” is not one man but many different people. There is some truth to that, he told me. Scores of Ghanaian citizens, protesting corruption as part of a “Je Suis Anas” campaign, have taken to wearing their own masks in public.

As soon as the initial shock over Hussein-Suale’s death wore off, Tiger Eye jumped back to work. It was a show of resilience, perhaps, or a way to escape from the fog of grief. Just weeks later, Anas released a new investigation, Galamsey Fraud , which he expected to be even harder-hitting than Number 12 . The film alleges that government officials accepted bribes to overlook illegal mining practices. In the backlash, he told me, laughing, he was accused of being an illegal miner himself.

The mining investigation didn’t garner the international attention of the soccer exposé, but it may be a significant test for one of Ghana’s newest institutions: the Office of the Special Prosecutor, created last year following a campaign promise by President Nana Akufo-Addo to be tougher on corruption. Unlike the attorney general, who is appointed by the president, the autonomous special prosecutor is free to investigate and prosecute those in positions of power—such as the ruling-party staffers implicated in Galamsey Fraud . Anas’s legal team has provided the prosecutor’s office with documents related to its investigation and is waiting to be called.

“This is the problem I have with my friends from the West: I think they are asleep,” Anas told me. “You see now, it is the citizens who are doing the journalism for you. They are the ones going on the street and filming the police harassing them. What are you doing? Are you not asleep to assume that your legislature is fine, your executive is fine, your judiciary is fine, your police is fine?”

Before we parted ways—Anas had phone calls, more interviews, meetings, and a full travel schedule ahead of him—I asked him one last question: Do you have the energy to keep going? Anas laughed again, tilting his head back, and I could see the apples of his cheeks outlined against the beads. “Yes, man! A lot of energy! Look, the young ones: Are we just going to leave them in this quagmire?” he said. “Nooo—hell, no. I can’t fail. It took people to let the dictatorship slip in; it took people to push it back. No matter what it is, even if dictatorship started today, the fight would have to begin again.”

Susana Ferreira is a freelance journalist, producer, and writer.

Former Kotoko Player George Asare elected SRC President at PUG Law Faculty

Former Kotoko Player George Asare elected SRC President at PUG Law Faculty

2024 elections: Consider ‘dumsor’ when casting your votes; NPP deserves less — P...

2024 elections: Consider ‘dumsor’ when casting your votes; NPP deserves less — P...

You have no grounds to call Mahama incompetent; you’ve failed — Prof. Marfo blas...

You have no grounds to call Mahama incompetent; you’ve failed — Prof. Marfo blas...

2024 elections: NPP creates better policies for people like us; we’ll vote for B...

2024 elections: NPP creates better policies for people like us; we’ll vote for B...

Don’t exchange your life for wealth; a sparkle of fire can be your end — Gender ...

Don’t exchange your life for wealth; a sparkle of fire can be your end — Gender ...

Ghana’s newly installed Poland train reportedly involved in accident while on a ...

Ghana’s newly installed Poland train reportedly involved in accident while on a ...

Chieftaincy disputes: Government imposes 4pm to 7am curfew on Sampa township

Chieftaincy disputes: Government imposes 4pm to 7am curfew on Sampa township

Franklin Cudjoe fumes at unaccountable wasteful executive living large at the ex...

Franklin Cudjoe fumes at unaccountable wasteful executive living large at the ex...

I'll 'stoop too low' for votes; I'm never moved by your propaganda — Oquaye Jnr ...

I'll 'stoop too low' for votes; I'm never moved by your propaganda — Oquaye Jnr ...

Kumasi Thermal Plant commissioning: I pray God opens the eyes of leaders who don...

Kumasi Thermal Plant commissioning: I pray God opens the eyes of leaders who don...