As Missouri becomes the latest southern US state to pass anti-abortion laws, the president of the French National College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians says the college is “terrified” by what is happening to women's rights.

“When men intervene to tell women what they can do about pregnancy, then we are in a situation of regression,” says Israel Nisand, the president of France's College of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

To date, the American states of Missouri, Kentucky, Ohio, Utah, North Dakota, Arkansas, Mississippi, Georgia and Alabama have either passed or are trying to pass such bills. Alabama's is seen as one of the most restrictive legislations, as no exception is offered even in cases involving rape or incest.

The new bill would make it a Class A felony, the judicial equivalent of murder, for a doctor to perform an abortion. Those found guilty would face between 10 and 99 years in prison. Women would not face criminal penalties for getting an abortion.

Kentucky's proposed anti-abortion law was blocked by a judge.

The other states abide by the so-called 'heartbeat' standard, whereby an abortion is possible only in the first six to eight weeks of pregnancy, after which time doctors can often detect a fetal heartbeat.

“Those are just arguments to enable men to control the body of a woman,” retorts Nisand when asked about the 'heartbeat' reasoning.

But Georgette Forney, the co-founder of the Silent No More awareness campaign and the president of Anglicans for Life argues that, by imposing a limit beyond which an abortion can not take place, “we're actually protecting women from pressure and coercion. I'm still not completely convinced that we need to kill our children in order to get ahead in this world”.

Men vs women?

Many criticisms of the reasoning behind such laws stem from the fact that the majority of those with voting rights in the state legislatures are men.

In the recent case of Alabama for example, of the 35 senators, 25 are male. The governor, Kay Ivey who signed the bill into law, is however, female.

Forney says such arguments are simply not true.

“This is one of those arguments that takes somebody down a rabbit hole that has no merit or basis in reality. To blame men in general and to just say that feminism is dead because men voted on this law. There are women in these houses, these local governments. Men and women vote on these things”.

The ups and downs of abortion

Abortion has not always been such a divisive issue in the United States.

Regulations for abortion go back to the 19th century according to Karissa Haugeberg, an assistant professor on the history of US Women and Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana.

“Before 1820, most states abided by English Common law which criminalised abortion after quickening…so people relied upon women to say when they first felt the fetus move. Abortion was permissible before a woman reported that she felt the baby move,” explains Haugeberg.

Post-1820s is when more focus was placed on criminalising the method of abortion when “a small handful of states sought to criminalise the sale of poisons, this is when there was a market of health-care providers and there were some nefarious people that were selling women chemicals and things, rat poison, things that were actually causing harm. So historians generally describe those as poison control measures,” rather than specifically targeting the act of abortion itself.

It's only in the mid-19th century when the seed for current anti-abortion laws started to take root.

“That's when every state in the union criminalised abortion” says professor Haugeberg, noting that exceptions were made if a woman's life was in danger.

This was around the time of the Civil War and coincidently the time of the “professionalisation of medicine in the US”.

Some argue that abortion was then targeted by physicians as a means of taking the market away from midwives so as to give credibility and legitimisation to trained physicians. They alone could determine if a woman's life was truly in danger.

But up until the 1940s baby-boom post World War II, “physicians for the most part were able to perform abortions including elective abortions without much interference by the state,” says the historian.

In fact, the rate of abortion rose during the 1930s at the time of the global economic depression and authorities “generally did not intervene, did not prosecute”.

The crackdown began in the 1940s, when police began “raiding physicians who had abortion clinics and prosecutors began enforcing those criminal statutes that had been on the books since the middle of the 19th century,” she explains.

Baby-boom

With populations decimated in the post-World War II era, there was a greater emphasis on big families. A similar trend was seen in France in the post-Great War era, with the pro-natalist movement.

In the US, this line of thinking was aimed at bringing women back from the wartime workplace to the home, with the basic idea “that a women's place in society is to be a mother”.

This changed in 1973 following the often quoted case at the US Supreme Court of Roe vs Wade. It essentially ensured a women's right to request an abortion. But since 1973 “for many women, abortion has been a legal right in name only, because in practice it's been unaffordable or inaccessible to many women and that's a trend that's actually gotten worse over time”.

Many point to the increasingly extreme nature of these bills across southern states as a provocation intended to ensure that the legislation will be appealed before the Supreme Court.

However, the recent wave of strict anti-abortion bills in the US has been welcomed by anti-abortion activists.

“I'm grateful for the passing of these laws and I think they're lining up much more with the opinion of the American citizens,” says Forney.

Outside the US

In France, since 1975, women have had a right to an abortion up until the 14th week of a missed menstrual period explains Nisand.

It is considered a woman's right and “the state has an obligation to provide such a public service”.

If a doctor has a crisis of conscience, he or she “must state that immediately at the consultation and refer the woman to someone else” adds the president of the National College of French Gynecologists and Obstetricians.

Geographical legal anomaly

In Northern Ireland, for example, the situation remains unchanged, despite the province's neighbours, Ireland and England having legal access to such procedures.

“We are still effectively governed under the 1861 Act” says Emma Campbell, the co-chair of the Alliance for Choice in Belfast.

The Offenses Against the Person Act was a British law brought in at the height of colonisation. At the time, Ireland was under British control.

Unless a woman is likely to die as a “result of her pregnancy or have severe long-term impact on her health, then there is no access to abortion, at any period of gestation,” explains Campbell.

But women in Northern Ireland, unlike in Alabama, can be penalised for seeking an abortion.

“There's a mother who was arrested for accessing pills for her 15-year-old daughter who was in an abusive relationship at the time. That's still going through the courts as it's been appealed. There is the story of the 19-year-old woman who was trying to save up to travel over to England for an abortion but she couldn't save up the money in time. So she accessed the online abortion pills and her flat mates called the police when they found what she'd done. And she was arrested and charged,” says Campbell.

Right to options?

“Unfortunately, having abortions as their own choice is often undermined with the level of pressure and coercion that women report feeling. Up to 70 percent of the women having abortions express feeling coerced and pressured; they aren't given a choice,” says the co-founder of the Silent No More awareness campaign.

The campaign aims to teach people that abortions have “negative consequences” and to help those who have undergone such procedures to seek help through healing.

Those from the pro-life spectrum argue in favour of protecting life and view the fetus as a human being since a heart is detected. Any effort made to purposely end that pregnancy is simply a form of killing, regardless of how a woman has become pregnant.

“I feel like as a culture we use rape as the justification for abortion and that really only represents one to two percent of the abortions in America,” explains Forney.

“But the reality is that we need to do better for women so that whether they are pregnant through rape or pregnant through a condom breaking or their birth control not being effective, that we're helping them understand that they're capable of being pregnant and going to college or being pregnant and maintaining a job.”

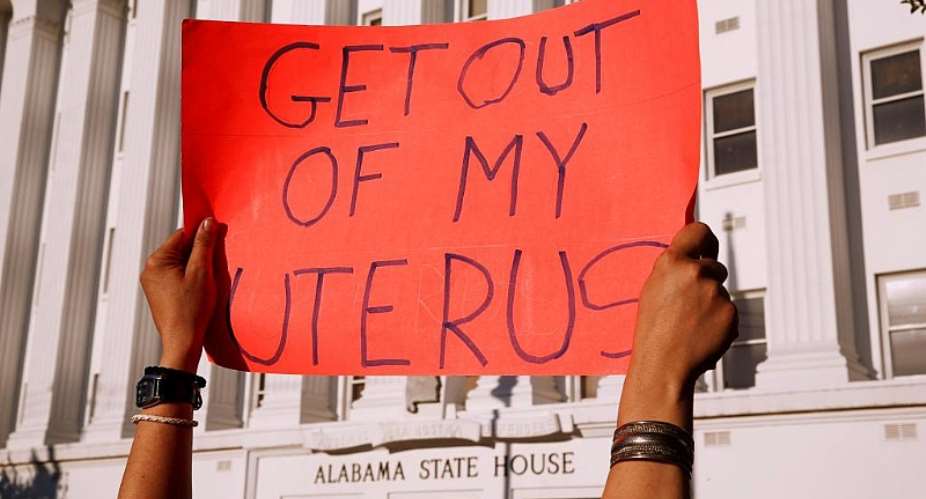

That may be so, but it didn't stop the hundreds of demonstrators from hitting the streets on 20 May in a march to the Alabama state capital to protest the new bill.

Many chanted “my body, my choice!”

And that is the recurring theme since the debate on abortion started.

Women have fought hard to have the right to choice. Finding ways to block one choice based on laws, medical findings or religious texts takes away from the concrete fact that a judgment is being passed on another person's body without her consent.

Added to that point is the fact that having a child out of wedlock is still not an easy feat given today's economy nor is it socially accepted in many circles, whether in western or non-western societies.

“95 percent of French people agree that abortion is a woman's absolute right. The other five percent, when it concerns their daughter, then they come to us and say' yes, I am against abortion, but for my daughter it has to be done',” explains Nisand.

April 20: Cedi sells at GHS13.63 to $1, GHS13.06 on BoG interbank

April 20: Cedi sells at GHS13.63 to $1, GHS13.06 on BoG interbank

Dumsor: I'm very disappointed in you for messing up the energy sector — Kofi Asa...

Dumsor: I'm very disappointed in you for messing up the energy sector — Kofi Asa...

Dumsor: Instruct ECG MD to issue timetable and fire him for lying — Kofi Asare t...

Dumsor: Instruct ECG MD to issue timetable and fire him for lying — Kofi Asare t...

Ashanti region: Road Minister cuts sod for 24km Pakyi No.2 to Antoakrom road con...

Ashanti region: Road Minister cuts sod for 24km Pakyi No.2 to Antoakrom road con...

Train crash: ‘How could any normal person leave a car on rail tracks?’ — Frankli...

Train crash: ‘How could any normal person leave a car on rail tracks?’ — Frankli...

Train crash: Driver of abandoned vehicle not our branch chairman nor secretary —...

Train crash: Driver of abandoned vehicle not our branch chairman nor secretary —...

Kenya pays military homage to army chief killed in copter crash

Kenya pays military homage to army chief killed in copter crash

US agrees to pull troops from key drone host Niger: officials

US agrees to pull troops from key drone host Niger: officials

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...