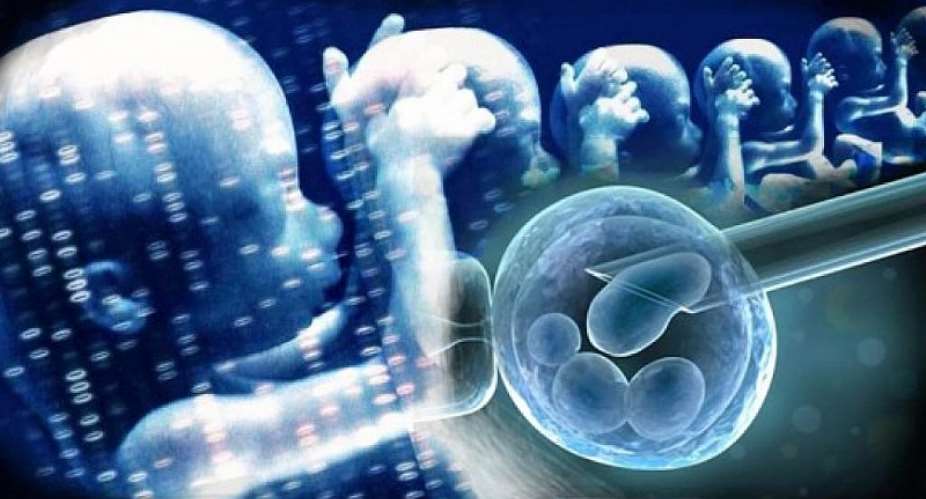

Experts from the World Health Organisation are meeting in Geneva Monday to discuss the future of human gene-editing – amid calls from scientists and ethicists for a global ban on the use of technology that could result in genetically modified babies.

The global ban would specifically concern altering human DNA that can be passed from one generation to the next, the so-called germline. It would be a five-year moratorium with the aim of devising an international framework to encourage scientists to do the right thing.

“The call is for a temporary freeze on the clinical applications of germline editing,” explains Dimitri Perrin, a senior lecturer at Australia's Queensland University of Technology . “It's not saying that we should stop research on embryo editing; it's just saying that it is too soon to carry out that technology clinically.”

The push to clamp down on germline editing – which came from 18 scientists and was published in the journal Nature – follows international outrage that erupted when the Chinese researcher He Jianku illegally used CRISPR gene-cutting scissors to edit embryos that led to the birth of twin girls.

Some scientists opposed to moratorium

Not everyone is lending their support to the idea of a moratorium though. Dr Helen O'Neill, programme director of reproductive science and women's health at University College London told the Science Media Centre that such a move risked shedding a negative light on the potential for germline genome editing that would have huge consequences for research funding.

“Currently, there are legal and ethical measures in place globally which regulate the use of gametes and embryos,” O'Neill says. “Let's not forget that He Jiankui broke many rules, and was aware of this by choosing to do his work outside of the auspices of the university … It was not that he did this because the law allowed it.”

Perrin concedes that in many countries a ban on germline editing already exists, but says the idea is to try to have an international consensus on how to move forward with the technology.

“It's true most countries in Europe, for instance, have signed the convention on human rights in biomedicine, and in that convention modifications that would be inherited across generations are banned by default,” Perrin says.

“This proposed moratorium would bring together various stakeholders – researchers, clinicians, ethicists and the general population – for an open discussion about how and when Crispr should be used.”

Technology advancing too quickly

Countless unanswered questions surround the use of the Crispr (Clustered Regularly-Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) and the dangers it poses. There are fears the technology could cause cells to lose the ability to fight cancer, or it could create incurable diseases. There's also the risk of ushering in a new era of human inequality.

Dr Gaetan Burgio, a geneticist at the John Curtin School of Medical Research at the Australian National University in Canberra, warns: “We don't know exactly what Crispr does in the cell. We have learned a lot, but we still have more to learn. We must be assured that it works and we must ensure absolute safety for all clinical use and we're not in that position yet.”

The moratorium won't stop rogue scientists like He from meddling with human embryos, Burgio adds, but it can certainly reduce their motivation for wanting to do so.

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...