The end of what has been wrongly referred to as World War II saw many nationalists around the so-called third world countries agitating for political freedom. In the case of Africa, the fact that Africans had fought to consolidate the self-determination of Europeans was enough reason to inspire a spontaneous outcry against western domination and imperialism.

In the course of the struggle against European, many strategies were proffered. The likes of Franz Fanon were of the opinion that violence should be used to overthrow the yoke of European colonialism. The reason, according to Franz Fanon was/is not far fetched: colonialism was based on violence. Fanon’s prescription was applicable to settler colonies, like Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Even so, he recognized the penchant of the colonized to seek to mimic the colonizer. He metaphorized this as the colonized infatuating after the wife of the colonizer.

There were also individuals like Mahatma Gandhi who opted for positive defiance. Gandhi argued that violence begets violence. Hence, it was necessary to use non-violence and the force of truth (Satyagraha) to stem the tide against colonialism. This strategy was applied in many non-settler colonies, including Ghana. Kwame Nkrumah’s use of positive defiance was largely a Gandhian influence.

At the end whether through violence or peaceful means, the basic motivation for the struggle against colonialism was that getting rid of the colonizer was constructed as the sure means to prosperity. Since colonialism had inscribed violence on the body and psyche of many Africans, the sole panacea to it was self-determination. Nkrumah inverted the Christian text that in ways sought to provide a greater force for the struggle against colonialism. When he averred that the people of Gold Coast should, ‘seek first the political Kingdom, and all other things shall be added to it,’ he was advancing some epistemic tradition that saw colonialism as the basic challenge to the prospects of Ghanaians.

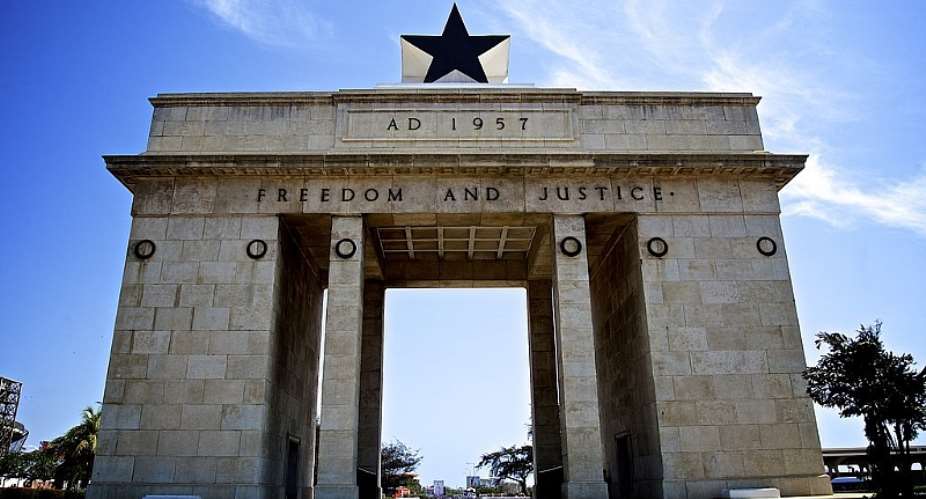

In the end, many women, men, youth, the sick, the healthy, and some Africans in the Diaspora participated in the wave to bring the stronghold of colonialism down. The struggle for self-determination in the Gold Coast was not easy (but it was not as bloody as the case in settler colonies). But eventually, we became ‘freed’ people. We replaced the Union Jack with the flag of Ghana. The colors of Ghana’s flag were carefully chosen to reflect the multiple dimensions of our history and culture. Important for me is the color red, which symbolized those who supposedly laid down their lives for the political independence of the country. I find this symbol quite misleading, as it creates a hero narrative that simply did not exist. Did anyone actually die for Ghana’s independence? Did the three ex-servicemen actually lose their lives directly because of Ghana’s independence?

Be that as it may, by 1944, the name Ghana had been suggested to replace Gold Coast (which was a colonial imposition). While we changed the name, we still maintain our linguistic ties to the British. For reasons that would be explored later in another article, the nationalists did not suggest forceful enough any national language for the country. While Ghana was ready for political independence by 1954, the formation of the National Liberation Movement (NLM) by some youth and political elites of Asante, and the Eve Question postponed the country’s independence until March 6, 2019.

Shortly after independence, many groundbreaking projects were pursued. Key among them was the Akosombo dam. The key players in the planning and implementation of the dam project were Kwame Nkrumah, John Kennedy (former president of the United States of America) and Harold Macmillan (former Prime Minister of Britain), Edgar F. Kaiser, and the World Bank. The dam, which is basically a single-purpose hydroelectric power generation, built between 1961-1965 and started operation in 1966. It is the biggest man-made lake in Africa. Its main purpose is to support the industrialization and general development of Ghana, while some of the power it generates is exported to neighboring countries. The dam, which has been in operation for about 54 years, remains the main source of electricity supply for Ghana. There were other monumental achievements, including the Tema Motorway. Lightweight industries also mushroomed in some parts of the country.

Notwithstanding these achievements, a few years after political independence, the euphoria that birthed the nationalist agenda began to wane. Farmers (particularly cocoa farmers) started complaining about poor purchasing price for their produce. This partly contributed to the formation of NLM. There were others who felt Nkrumah had become power-drunk. The passage of some draconian laws like the Preventive Detention Act in 1958 (which was part of the communist strategies) and the declaration of Ghana as a de jure one-party state in 1964 incensed Ghanaians about the autocracy of Kwame Nkrumah. The cumulative effect of these grumbling was that in 1966, a group of soldiers and policemen with the support of the American Center for Intelligence Agency toppled the government of Kwame Nkrumah. After Nkrumah, Ghana recorded four other successful coups.

The multiple coups Ghana experienced contributed to the underachievement of the country. This was because most of our uniformed men lacked the expertise to run the nation. Their interference in civilian regimes set Ghana on the path of retrogression. Over the years, I have been thinking about the reasons for Ghana’s underachievement, beyond the rhetoric of slavery and colonialism. About a decade ago, I read an insightful book, ‘The Generation of the Races,’ authored by Zipporah Koranteng. The book sought, inter alia, to discuss the reasons for the challenges that have burdened Ghana and Africa. While she contested against the so-called Hamitic curse, she asked a very important question: “Did Noah bless Ham when Noah was re-blessing his children?”

Many scholars (particularly those with a strong aversion for the Bible) will summarily dismiss the story of Noah as one of the etiological myths of the Bible. But for many others, Koranteng’s question deserves attention. When I went to the University of Cape Coast to read African Studies, one of my quests was to understand the place of Africa in Christian eschatology. Prior to my university education, I had read quite extensively about Christian eschatology, but there was not a single book that mentioned the role of Africa in the climax of time. While this could be because the authors were non-Africans, the point is that most African biblical eschatologists never mention Africa in their exposition either.

I also read another important book, ‘African Renaissance’, by Sampson Joe Banning, whose diagnosis of the African predicament was illuminating. Aside from these two authors, Martin Meredith’s ‘The State of Africa’ and Kofi Awoonor’s, ‘The African Predicament’ made a good impression on my mind. Indeed, long before these writers, Ibn Khaldun and Hegel had attempted to answer Africa’s predicament. They pointed to what is now referred to geographical determinism. Jared Diamond, a recent scholar, also subscribed to the notion of geographical determinism. By geographical determinism, these scholars maintain that the location of Africa – where there are lots of material resources – frustrates Africans from thinking deeply about life. In other words, because the continent of Africa has so many resources, Africans do not think well enough to catapult their development.

These theories may or may not convince you. But the fact of the matter is that the ideals that birthed the nationalist agitation against colonial rule have not been realized. In the twenty-first century world, Ghana (among many African countries) continue to struggle with the colonial legacies of underdevelopment, characterized by poor sanitation and squalid living conditions, high levels of poverty, illiteracy, corruption, ethnocentrism, religious fanaticism, and partisan politics. The frustrations in living in Ghana led one man to conclude that, ‘To be a tree in Europe is better than to be a human being in Ghana.’

The irony of our predicament is that almost every Ghanaian knows what is wrong with the country, and almost every Ghanaian knows what the solutions are. But as to why we are still not developed, that is left to all manner of speculations. Reading Jonathan Sacks, a philosopher and former national chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom, I came to appreciate how we respond to calamities in life. Jonathan Sacks argued in his book, ‘Not in God’s Name’ that when calamity befalls us, we have two options open to us: penitential culture and blame culture. Penitential culture assumes that the victim played a role in the calamity. This admission helps the victim to avoid the recurrence of the calamity. There is also the blame culture, where the victim absolves himself or herself of any contribution to the calamity. Either of the options has implications for development. In the case of penitential culture, the victim endeavors to avoid the repetition of the calamity. On the other hand, in the case of the blame culture, the victim is doomed to live in the quagmire of repeating the calamity (samsara).

My reading of the history of Ghana is that we always take the position of blame culture. The easiest we do is to blame the twin-evils – slavery and colonialism – for our underachievement. We hardly take the position of having contributed to these two evils. In the end, we keep repeating them. The rise of child slavery and the challenge of ‘galamsey’ are emblematic of how we are shackled in the backwaters of history. The idea of historical parallelism is real in our case. We blame our corruption and economic mismanagement on the Bretton Woods Institutions. We blame our ineptitude on neocolonialism. We are never responsible for our predicament. Externalizing the reasons for our problems deadens our conscience. It gives us comfort to remain where we are. Ghana Awake! Indeed, we had good reasons for political independence, but the reality we are faced with communicates a different narrative. Happy Independence Day!

Satyagraha

Charles Prempeh ([email protected]),

African University College of Communications, Accra

2024 election will be decided on the grounds of the economy; choice of running m...

2024 election will be decided on the grounds of the economy; choice of running m...

Dumsor: We're demanding less; just give us a timetable — Kwesi Pratt to ECG

Dumsor: We're demanding less; just give us a timetable — Kwesi Pratt to ECG

Do I have to apologise for doing my security work, I won’t – Simon Osei-Mensah r...

Do I have to apologise for doing my security work, I won’t – Simon Osei-Mensah r...

Prestea and Bogoso mines: Complete payment of outstanding salaries not later tha...

Prestea and Bogoso mines: Complete payment of outstanding salaries not later tha...

NDC postpones Prof. Opoku-Agyemang entry tour to May

NDC postpones Prof. Opoku-Agyemang entry tour to May

All my businesses have collapsed under Akufo-Addo — NDC Central regional chair

All my businesses have collapsed under Akufo-Addo — NDC Central regional chair

Military, Prison Officers clash in Bawku, three injured

Military, Prison Officers clash in Bawku, three injured

GRA-SML contract: MFWA files RTI request demanding KPMG report

GRA-SML contract: MFWA files RTI request demanding KPMG report

Court threatens to call second accused to testify if NDC's Ofosu Ampofo fails to...

Court threatens to call second accused to testify if NDC's Ofosu Ampofo fails to...

Family accuses hospital of medical negligence, extortion in death of 17-year-old...

Family accuses hospital of medical negligence, extortion in death of 17-year-old...