Born in 1894 and enlisted after showing his prowess as a wrestler, Abdoulaye Ndiaye was a Senegalese villager who fought for France as a sharpshooter in World War I.

One of 600,000 soldiers recruited from the French colonies, Ndiaye was part of an infantry unit known as the "Senegalese Tirailleurs" (Senegalese Shooters) which took part in the 1915 campaign to open the Turkish Dardanelles strait between Europe and Asia.

A year later, while fighting in the Battle of the Somme, he suffered a head wound, which still gave him pain years later.

His military service card, now on display at the Army Museum in Dakar, states that Ndiaye hailed from Thiowor, a village with a population of 3,000 about 180 kilometres (110 miles) north of the capital.

On 11 November 1998, the soldier -- who spent the rest of his life a farmer -- was to have been decorated with the prestigious Legion d'Honneur, France's highest honour.

But just one day before, Senegal's last rifleman died. He was 104.

He died aged 104 just a day before he was to have been decorated with France's highest honour. By SEYLLOU (AFP/File)

He died aged 104 just a day before he was to have been decorated with France's highest honour. By SEYLLOU (AFP/File)

Several years earlier, he recorded the story of how he joined the army while working as a camel driver, after a wrestling match in which he was "invincible".

"He did many military exploits," recalled Babcar Sene, another villager in his 80s who fought for France in Indochina.

'Thiowor's most famous son'

"He is Thiowor's most famous son."

Decades after his injury, the head wound still bothered Ndiaye, his great-nephew Cheikh Diop told AFP. "He said it hurt to touch."

A memorial stone in his honour stands in the dusty northern village where he spent his life and where children still sing of his exploits.

After the war, he went home and simply returned to his work as a farmer.

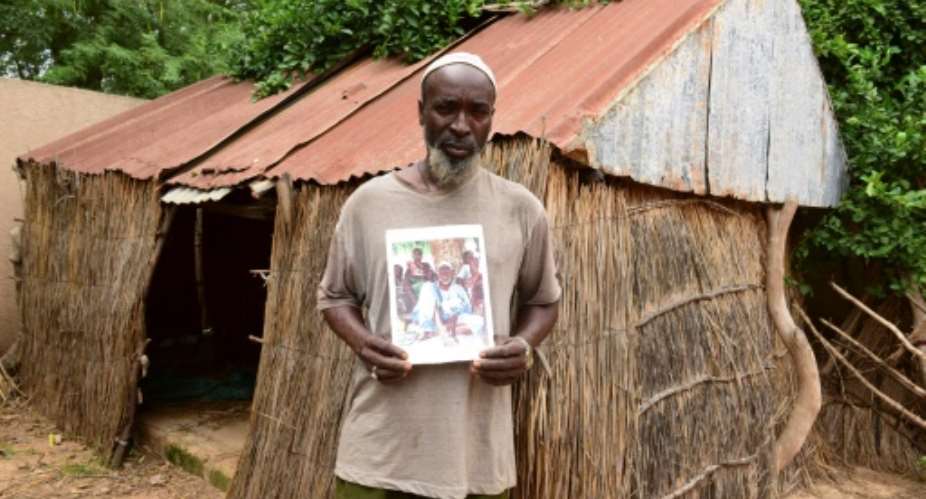

"He just went back to his life which revolved around this hut and this tree," said Diop, showing a dog-eared photo of his great-uncle leaning on a tree trunk, surrounded by children.

Plans to turn his makeshift hut and an extended family house next door into an Abdoulaye Ndiaye Museum never got much further than the construction in 2002 of a French-funded road.

A stadium being built on the outskirts of his village will bear his name. By SEYLLOU (AFP/File)

A stadium being built on the outskirts of his village will bear his name. By SEYLLOU (AFP/File)

Known as "Sharpshooters' Path", it is today pitted with holes, while the hut he called home is filled with a tangle of kettles, cooking pots, amulets and rusting teapots.

Two new rooms in the house destined in 2008 to form the museum along with the hut, at the initiative of sponsors of the Army Museum in Dakar, never opened.

"The museum has become a museum piece in itself," jested the soldier's grandson Babacar Ndiaye, while much of the memorabilia has vanished forever.

"Many papers and photos were destroyed in a fire," Babacar Ndiaye said regretfully.

But the sharpshooter's memory lives on among the villagers, and a stadium being built on the outskirts of the village will soon bear his name.

Reintroduce Fiscal Responsibility Act to tackle election budget overrun — Osafo ...

Reintroduce Fiscal Responsibility Act to tackle election budget overrun — Osafo ...

Flooding: Obey weather warnings – NADMO to general public

Flooding: Obey weather warnings – NADMO to general public

Fire in NDC over boycott of Ejisu by-election

Fire in NDC over boycott of Ejisu by-election

NDC to outdoor Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as running mate today

NDC to outdoor Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as running mate today

Ejisu: CPP seeks injunction to stop April 30 by-election

Ejisu: CPP seeks injunction to stop April 30 by-election

Dismiss ECG, GWCL, GACL bosses over losses – United Voices for Change tells gov’...

Dismiss ECG, GWCL, GACL bosses over losses – United Voices for Change tells gov’...

Submit 2023 audited financial statements by May – Akufo-Addo order SOEs

Submit 2023 audited financial statements by May – Akufo-Addo order SOEs

Current power outages purely due to mismanagement – Minority

Current power outages purely due to mismanagement – Minority

ECG hoists red flag to fight Ashanti Regional Minister over arrest of General Ma...

ECG hoists red flag to fight Ashanti Regional Minister over arrest of General Ma...

Mahama’s 24hr economy will help stabilise the cedi; it’s the best sellable polic...

Mahama’s 24hr economy will help stabilise the cedi; it’s the best sellable polic...