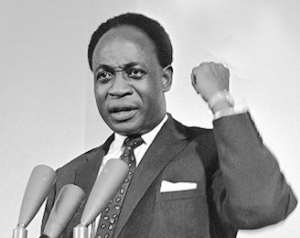

Accra, March 5, GNA - On the occasion of Ghana News Agency's 60th Anniversary, we submit here the speech delivered by Dr Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana's First President, as we go down memory lane to reflect the vision of the Agency.

SPEECH DELIVERED BY OSAGYEFO THE PRESIDENT AT THE FORMAL OPENING OF NEW OFFICE BUILDING FOR GHANA NEWS AGENCY - 18TH SEPTEMBER, 1965

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We are gathered here today to inaugurate this new and modern building of the Ghana News Agency. These offices are vastly different from the humble quarters, in James Town, where I first inaugurated the Ghana News Agency only eight short years ago. The growth of the Ghana News Agency, since 1957, symbolises in many ways the gigantic strides made by Ghana in eight brief years of independence. From humble beginning, and bearing the heavy burden of a colonial legacy, we are developing with great speed into a strong, progressive State with the great goal of socialism.

The journalist is one of the major architects of the new Ghana and of the new Africa. It is by his work that our people can have some idea of what we are thinking and know something of the events in Africa and the world. Through his eyes our people are made to know about the machinations of imperialism and neo-colonialism. It is by his pen that the will of the people can find expression and our determination to be free, to unite Africa, and to build a new society, is proclaimed for all the world to know.

The journalist writes about what is important; what is significant; what is striking; what is timely and what will interest a lot of people. Today, in Africa, what is foremost and important is the movement for the political unification of our Continent. What is striking and timely is the African revolution expressed in the search for the realization of this great goal and objective. It follows therefore, that our articles, our commentaries, our radio and television newscasts must be prepared and portrayed by revolutionary journalists, who see the world through the eyes of the revolutionary African.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I think we may say that journalism is, in a way, the art of seeing - of seeing what makes news; what is significant and interesting - and then conveying what has been seen to the reader in the most effective manner. However, what is seen differ according to the viewer: Two persons witnessing the same event may actually see different things. For example, the press of the entire world was present at Addis Ababa when the first Conference of all African Heads of State and Government was held in 1963. But what did most of the correspondents of the world commercial press write about that Conference, what did they see in that Conference? They saw only the cold war between East and West. In each of our resolutions, in each of our decisions, they looked only for imaginary victories or defeats of the socialist world or the capitalist world. It did not occur to them that our Conference might be an expression of the spirit of the new African.

They did not see the conference as a historic step towards the great goal of African Unity under a Continental Union Government. They saw the Conference only through their own eyes, in the light of their preoccupations and their interests.

A more recent example is provided by the events in the Congo Leopoldville. At the time of the imperialist aggression against Stanley Ville, the Western press shed tears only for the few so-called European hostages held by the revolutionary forces. This press showed little sympathy for the thousands of Congolese maimed and killed by neo-colonialist paratroopers and South African mercenaries.

Other examples could be given. What a journalist sees depend on what his past experience is; what his education has been; what his intelligence is; what political sense he has and what his general outlook on the world is - in other words, on his political consciousness and ideological background. The necessity for a clear ideology of the African Revolution must be to view problems in the right perspective so that they can write them with insight and understanding.

The drumbeat of the African Revolution must throb in the pages of his newspapers and magazines; it must sound in the voices and feelings of our newsreaders. To this end, we need a new kind of journalist of the African Revolution. He cannot help in the building of the new Africa, unless he himself has founded his conviction on the rock of a scientific understanding of the world around him.

In the West, much is made of the theory of the so-called 'neutrality' of the journalist and 'freedom' of his press. According to this theory, the reporter is a dispassionate observer who reveals no opinions or prejudices. He does not take sides, but allegedly simply sets down the facts, leaving it to his reader to draw his own conclusions. In this way he is deemed to be free to make impartial comments on national and international events.

But, in fact, as we all know, this theory of neutrality is hardly ever put into practice. The big news agencies, papers, radio and television reflect the bias and prejudices of their publishers and proprietors. This is shown in the choice of the stories which are published; the way the facts are arranged within each story or the manner in which the stories are placed on the page. African revolutionaries fighting heroically for the freedom of their country in so-called Portuguese Guinea, Angola, Mozambique and elsewhere are called rebel bands, while the counter-revolutionary Cubans scheming in Miami and Caracas are called 'Freedom Fighters'. Many events are hushed up or distorted. You know how Ghana has become a victim of distortion by a section of the Western press, because of our irrevocable stand against the economic exploitation and political subjugation of Africa and its people.

We are emerging from colonialism, and we are being stifled by imperialism and neo-colonialism. We face a long, hard life-and-death struggle in which all of our people are engaged. How can the journalist be 'neutral' in circumstances as these?

We are in a revolutionary period, and we have a revolutionary morality - in journalism as in all other walks of life. We cannot be neutral between the oppressor and the oppressed; the corrupter and the victim of corruption; between the exploiter and the exploited; between the betrayer and the betrayed. We do not believe that there are necessarily two sides to every question; we see right and wrong; just and unjust; progressive and reactionary; positive and negative; friend and foe. We are partisan.

There is a qualitative difference between our revolutionary journalism and the journalism of the imperialist countries. This difference lies mainly in the content of our journalism, the purpose for which our stories are written, and the audience towards which they are directed.

First, our choice of stories is often different, for we pay little attention to cheap sensationalism, scandal, crime and gossip. The popular press of the imperialist countries and neo-colonialist regimes is on the contrary full of articles concerning the wealthy; private lives of exiled queens and dukes and movie stars, who make up what is known as café society. Secondly, our journalists view and analyse through the spectrum of our revolutionary ideology. Armed with our ideology, we can detect a trend in a seemingly minor event. For example, we know, even if the imperialists did not, that the scattered shots fired in Algeria on November 1, 1954, sounded the death knell of colonialism in that country; and we who were present knew, even if the colonialists did not, that the first and the last Pan-African Conference held in Manchester by a handful of nationalists heralded the eventual triumph of the African independence movement. Armed with our revolutionary ideology, we can detect a pattern in a series of apparently unrelated events; for we can see, even if the imperialists do not wish us to see it, the interconnection between the fighting in the Congo, the fighting in Angola and Mozambique and in the Dominican Republic, and the fighting in Vietnam. The struggle against imperialism is indivisible.

The revolutionary journalist must have a clear conception of his social aims in writing each story. The revolutionary journalist must write to inform the people, because in our African society, the destiny of all is linked up with the destinies of each. The journalist must inform the people of what their Government is doing; of what their compatriots are doing and of what other peoples in similar situations are doing throughout the world. He must inform them of the plots and intrigues of the imperialists; the ceaseless attempts at bribery and corruption by intelligence agencies and of steps that are being taken to defeat the African renaissance. Our journalists must write to educate the people.

The world of today is extremely complex, and Africa, with its legacy of colonialism must liberate itself with the right knowledge and the open pen of truth.

The revolutionary journalist writes for the people. His audience is first and foremost Africa, and then the rest of the world. Therefore, he bears in mind the interests; education and psychology of this audience in everything he writes. He is not writing for the elite. He is writing for the masses - for our workers; our farmers; our clerks and bus and taxi drivers - because all of our strength and all of our achievements spring from them. The common man of Africa is our strength. The journalist, therefore, must be close to the masses; he must see the world through their eyes and interpret events in a way in which the masses can readily understand.

The role of the journalist of the African Revolution is no mean one. He must help to defeat imperialism and neo-colonialism, help with the speedy transformation of Africa as a unified Continent. It is the privilege of the journalist to participate in this historic movement.

The role of the journalist here in Ghana has been easier than in other countries. We have not been called upon here to make the blood sacrifices of the heroes of Stanley Ville; the martyrs of South Africa, or the guerrillas of Algeria or Angola. But in the main, we have only to march forward, confident in our strength and in our final victory. Our journalists have the high responsibility of contributing to our victory, educating the people and inspiring them. In this sense they are in the vanguard of our revolution. It is their duty and responsibility to hail those who advance the revolution and expose those who retard it.

These, fellow journalists, ladies and gentlemen, are some of my reflections on the role of the journalist in Ghana and in Africa, which I would like to share with you. I hope that they may be of interest to those of you who are already established journalists, and to our youth who are preparing themselves for this exciting profession.

And now, I take great pleasure in unveiling this plaque to mark the formal opening of the new office building of the Ghana News Agency.'

GNA

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...