RIPOLI, Libya, Dec. 11 - When Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi proposed a borderless United States of Africa several years ago, Kofi Bafoo in Ghana answered his call.

Like hundreds of thousands of other young men living in the impoverished countries along the Sahara's southern fringe, Mr. Bafoo left for this oil-rich promised land with hopes of building a new life on the Mediterranean coast.

It did not work out that way. Few of the estimated one million Africans who flooded into Libya found jobs in the country's feeble economy, so Mr. Bafoo and thousands of other young African men set their sights on European shores. Libya, it seems, was happy to let them go.

"Until 2003, every day boats were leaving," Mr. Bafoo said, limping on a foot injured recently while running from the police. "The government knew about it, but they didn't care."

The problem began a decade ago. Colonel Qaddafi, frustrated by his failures to build pan-Arab unity and the Arab world's lack of support for him in the face of United Nations sanctions imposed in 1992 to press Libya to deliver suspects in the bombing of a PanAm flight over Lockerbie, Scotland, turned his attention south. After African countries agreed to defy the sanctions by resuming flights to Libya in 1998, Colonel Qaddafi renamed the country's Voice of the Greater Arab Homeland radio station the Voice of Africa and began talking in earnest about his pan-African plans.

But last year the sanctions were lifted, and Libyan leader has shifted his focus again, this time from Africa to new friends in the West who are eager to stop the African migration to Europe. The Libyan authorities have begun arresting and deporting those caught without a valid visa, even though visa requirements had been abolished earlier as part of Colonel Qaddafi's African outreach.

"For years, Libya said it could not play policeman for the West, but now, with the rapprochement, Libya has entered into a dialogue to deal with the situation," said Saleh Ibrahim, director of an academic institute close to the Libyan leader.

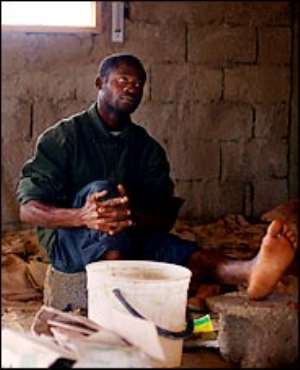

Mr. Bafoo, 25, tried to emigrate last year but lost $1,000 to an unscrupulous intermediary who made off with the cash. Last January, he lost $1,200 when the Tunisian Navy intercepted his boat and sent him back to Libya.

The Libyan police arrested him a few days ago and took his last $500. He hurt his foot when he escaped by scrambling over a cinder-block wall.

"They discriminate by the color of your skin," complained Mr. Bafoo, his injured foot smeared with massage cream because he has no identity papers or money for a hospital.

The boat people leaving from Libya are part of a broader wave of Europe-bound illegal immigrants from all along the North African coast, but nowhere has the passing been as easy or the traffic as heavy as it has been from here.

"We have cooperation with Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, but there have been no formal relations with this country and that has created a gap," said a European diplomat in Tripoli who has been involved in talks on how best to stem the tide.

Some of the Africans here say there was a rush of boats leaving Libya in recent months as people took their chances before the seas turned rough in November. More than 1,500 people landed on the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa in October.

Libyan officials insist that their country has not abandoned Colonel Qaddafi's pan-African vision, but they say the problem has grown to a scale that cannot be ignored. Although Libya is now pushing Europe and the United States to increase investment in sub-Saharan Africa in the hope of keeping young men there, many of the Africans lured here by his past promises feel betrayed.

"Libya told all the Africans, 'Libya is Africa so you can come,' but many more people came than the country could handle," said Abbas Albal Kindam Yusef, a migrant from Sudan's troubled Darfur region. "Now they want us to leave."

Drinking water from a communal tin cup in Tripoli's crumbling old city, another Sudanese migrant, Sadiq Ataia, said 700 of his countrymen had been caught in the previous three days. Like most of the Sudanese here, Mr. Sadiq is from Darfur and claims allegiance to an opposition group fighting the government in Khartoum. He and other Sudanese say Libya is deporting Darfurians to Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, where they face an uncertain future.

"We're very afraid because we have no passport and no visa," Mr. Sadiq said. He said he had worked as an intermediary for smugglers, finding candidates for the dangerous Mediterranean crossing, but added that many smugglers had been arrested in the current crackdown and the rest were afraid to act. "Now, it's impossible to leave," he said.

There’s nothing you can do for us; just give us electricity to save our collapsi...

There’s nothing you can do for us; just give us electricity to save our collapsi...

Ghanaian media failing in watchdog duties — Sulemana Braimah

Ghanaian media failing in watchdog duties — Sulemana Braimah

On any scale, Mahama can't match Bawumia — NPP Youth Organiser

On any scale, Mahama can't match Bawumia — NPP Youth Organiser

Never tag me as an NPP pastor; I'm 'pained' the 'Akyem Mafia' are still in charg...

Never tag me as an NPP pastor; I'm 'pained' the 'Akyem Mafia' are still in charg...

Your refusal to dedicate a project to Atta Mills means you never loved him — Kok...

Your refusal to dedicate a project to Atta Mills means you never loved him — Kok...

2024 elections: I'm competent, not just a dreamer; vote for me — Alan

2024 elections: I'm competent, not just a dreamer; vote for me — Alan

2024 elections: Forget NPP, NDC; I've the Holy Spirit backing me and nothing wil...

2024 elections: Forget NPP, NDC; I've the Holy Spirit backing me and nothing wil...

2024 elections: We've no trust in judiciary; we'll ensure ballots are well secur...

2024 elections: We've no trust in judiciary; we'll ensure ballots are well secur...

Performance tracker: Fire MCEs, DCEs who document Mahama's projects; they're not...

Performance tracker: Fire MCEs, DCEs who document Mahama's projects; they're not...

Train crash: Railway ministry shares footage of incident

Train crash: Railway ministry shares footage of incident