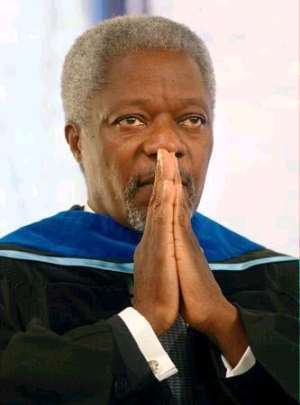

The United States is leaving open the option of pushing for U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan to step down, amid calls from U.S. lawmakers for his resignation.

Officials in the State Department indicate the White House is considering the extent of the alleged corruption within the U.N. oil-for-food program, no longer in use in Iraq. It remains unclear whether the U.S. will take the extraordinary step of pushing for the secretary general to resign.

Such a move by the U.S. would further splinter the international community. While the possibility remains unlikely, the U.S. in recent days has taken an oblique diplomatic posture. Publicly, U.S. officials have both praised Annan for backing the internal U.N. investigation while leaving open the option to push for his resignation.

On Wednesday, the head of a Senate investigation into alleged U.N. corruption, Sen. Norm Coleman, R-Minn., called for Annan to step down. In an interview, Coleman said “we are on the path” to withholding funding from the United Nations should the secretary general remain in the post, “because we are not seeing the transparency.”

The United States is the largest contributor to the United Nations, providing for more than a fifth of the overall budget. The White House has not endorsed the threat of withholding funds from the international body, while concurrently not challenging it. But on Wednesday, the U.S State Department stepped up pressure on the U.N. by endorsing Coleman's findings.

“[Annan] was in charge of the United Nations at a time when Saddam Hussein ripped off over $20 billion,” Coleman said. “The buck has to stop somewhere. And if we are ever to get to the bottom of this, figure out who benefited and how they benefited, the guy at the top has to step down.”

The chairman of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Coleman's probe found that Saddam Hussein siphoned $6.7 billion in revenue from the oil-for-food program. In addition, the panel found that Saddam made an additional $13.7 billion through smuggling oil, in violation of international sanctions.

President Bush told reporters on Thursday that he looks forward “to the full disclosure of the facts.”

When pressed on whether Annan should resign, Mr. Bush avoided a direct response. "On this issue,” the president answered, “it's very important for the United Nations to understand that there ought to be a full and fair and open accounting of the oil-for-food program.”

There are six separate investigations, including Coleman's and a wide-ranging U.N. probe that has rankled U.S. lawmakers by its secrecy.

“In any other organization, if the CEO was around at the time when there was a $21 billion rip-off, the board of directors would say it's time to go. The problem with this is that some of the board of directors, the Security Council, are those that have been implicated,” Coleman continued.

“Unless folks see us getting to the bottom of this, I think the U.S. relationship with the United Nations is jeopardized,” the senator added. “We can avoid that by Kofi himself taking responsibility and stepping down.”

Though the alleged corruption involves key members of the U.N. Security Council – China, Russia and France – the United States finds itself on a diplomatic tightrope.

The U.S. has not been linked to the corruption, but it was aware of kickbacks involving billions of dollars within the oil-for-food program, long before making it public.

U.N. experts point out that sanctioned regimes invite black markets. Like fellow Security Council members, the United States gave Saddam Hussein the executive power to determine who received the oil-for-food contracts.

Experts and U.N. insiders speculate that this is one reason the United States has been slow to undermine Annan's power.

“There might be a significant price to pay for Washington in picking such a fight at a time when it is already trying to mend fences with partners like Canada, Europe, and elsewhere, where relations have become deeply strained and where Annan enjoys high moral authority as a spokesman for the global interest,” said Jeffrey Laurenti, a senior scholar on the United Nations at The Century Foundation.

“But if there is a smoking gun then the whole international dynamic could change,” the longtime U.N. analyst continued. “The question is whether this is another invented scandal like Whitewater, where in the end there is nothing real there, or whether there is an indictable offense or high level corruption. Because so far there is a lot of smoke, just as there had been with Whit water, but so far, no fire, as with Whitewater.”

No evidence has been made public linking the alleged corruption to Annan. The “fire,” as Laurenti put it, has not been shown.

The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, John Danforth, said earlier this week, “I don't think that the U.S. government rushes to judgment before all the facts are in.”

Annan has riled U.S. conservatives. He suggested to the BBC that the war in Iraq was illegal. He took a position on stem cell research in opposition to the Bush administration, stating that the U.N. should not prohibit therapeutic cloning. Annan also suggested that exemptions for peacekeepers from the international criminal court should not be renewed, again opposing a long-held U.S. stance.

But Annan has called for international support for Iraqi elections. And Annan was the U.S. candidate of choice for secretary general in 1996 when it opposed his predecessor's aspirations for another term.

Annan acknowledged for the first time on Monday that his son, Kojo Annan, received payments until February 2004 from a Swiss-based firm involved in oil-for-food contracts, even though his son's employment with the firm ceased in 1998.

The secretary general told reporters he was “very disappointed and surprised” that his son received payments. Detractors argue that the payments are tantamount to bribes.

Annan would not speak to the matter, only emphasizing his son's autonomy. “I don't get involved with his activities and he doesn't get involved in min,” he added.

But as one U.N. observer put it, “No one expected Jimmy Carter to resign when he was trying to line up business with Libya. Nobody expected elder Bush to resign when his son Neil was doing whatever he was doing with Silverado [a savings and loan company scandal in the early 1990s].”

The U.N. oil-for-food program was started in 1996 to allow Iraq to export oil in order to purchase basic goods for its people.

All five U.S. congressional investigations have pushed for the independent U.N. inquiry, led by former U.S. Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker, to hand over internal U.N. documents related to program.

Volcker said he would not release the documents until his initial report on individual corruption is out in January. To congressional Republicans, this is further evidence of an investigation that lacks transparency. Generally, congressional Democrats have not called for Annan to resign, though they support the Capitol Hill probes.

Joining congressional Republicans, many influential conservatives in the U.S. media are calling for Annan's resignation. Magazines from the National Review to the New Republic to New York Times conservative columnist William Safire have all called for Annan to step down.

Sen. John Ensign, R-Nev., has stated that in January's new Senate session he will introduce the U.N. Oil-for-Food Accountability Act, which would call for the United States to withhold 10 percent of its funding in the first year and 20 percent in the second year. Under former President Clinton the United States did refuse to pay some of its U.N. dues in protest.

The former Soviet Union forced the first secretary general to resign in the early 1950s by refusing to recognize him. In the interview, Coleman acknowledged that if the U.S. withdrew funding it would amount to a materaial and diplomatic statement that Annan should step down.

“[Annan's] in some trouble, but not that deep,” said Ed Luck, a onetime senior consultant to the U.N. General Assembly and now an international affairs professor at Columbia University. “First of all, most member states aren't that interested in this issue. Secondly, the blame lies mostly in the French, Russians and Chinese. Thirdly, the [U.S.] administration still needs him.”

The United Nations released a report on Tuesday that calls for long-sought U.N. reform. It proposes two options to improve the power imbalance in the Security Council as well as what could be a landmark agreement on the definition of terrorism, should it be endorsed by the international community.

It also proposes giving the International Atomic Energy Agency a standing right to inspect nuclear facilities, a power Washington may view as pivotal as it steps up pressure on Iran's and North Korea's nuclear programs.

“We knew this was going to be hard,” Annan told reporters. “And with the oil-for-food business, it's going to be even harder.”

But inside the U.N. secretariat there is no indication Annan, whose term is up in December 2006, is even considering stepping down. To the contrary, the prevailing view is that the calls for his resignation are ideological.

Yet some experts argue it's a mistake to reduce the scandal to one solely coming from the U.S. political right.

“It looks like it was not good management; it looks like he should have reacted sooner to the reports,” said Luck, who is writing a book on the Security Council.

“I think they misjudged oil-for-food as a politically motivated, ideologically motivated attack from people who never wanted to give the time of day to the U.N to begin with,” Luck added. “So I think they badly underestimated it.”

Critics fear Togo reforms leave little room for change in election

Critics fear Togo reforms leave little room for change in election

Flooding: Obey weather warnings – NADMO to general public

Flooding: Obey weather warnings – NADMO to general public

Fire in NDC over boycott of Ejisu by-election

Fire in NDC over boycott of Ejisu by-election

NDC to outdoor Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as running mate today

NDC to outdoor Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as running mate today

Ejisu: CPP seeks injunction to stop April 30 by-election

Ejisu: CPP seeks injunction to stop April 30 by-election

Dismiss ECG, GWCL, GACL bosses over losses – United Voices for Change tells gov’...

Dismiss ECG, GWCL, GACL bosses over losses – United Voices for Change tells gov’...

Submit 2023 audited financial statements by May – Akufo-Addo order SOEs

Submit 2023 audited financial statements by May – Akufo-Addo order SOEs

Current power outages purely due to mismanagement – Minority

Current power outages purely due to mismanagement – Minority

ECG hoists red flag to fight Ashanti Regional Minister over arrest of General Ma...

ECG hoists red flag to fight Ashanti Regional Minister over arrest of General Ma...

Mahama’s 24hr economy will help stabilise the cedi; it’s the best sellable polic...

Mahama’s 24hr economy will help stabilise the cedi; it’s the best sellable polic...