As you have been following this page on prostate world, I know this column has impacted on lots of men’s prostate health. This article is a very important one I want to share with my readers. I pick this article from the Men’s Health Newsletter I came across as I do my research and very interesting. www.menshealth.com/health/coping-prostate-cancer.

The article is about a patient diagnosed with prostate cancer sharing his story. You can read it now!

It's June 20th, the first day of summer in 2008. I'm knocked out on an operating table and a robot is removing my prostate gland. In April I learned I had stage II prostate cancer, and after questioning experts and survivors, I've decided surgery is the way to go. Let's git 'er done. My mom died of cancer, but not me. No way.

Now, almost 2 years later, I'm not going to say, "thank god they caught it in time...I'm so blessed, each new morning is a miracle...Blah blah blah blah."

No, what I'm thinking is more along the lines of: I want my prostate back.

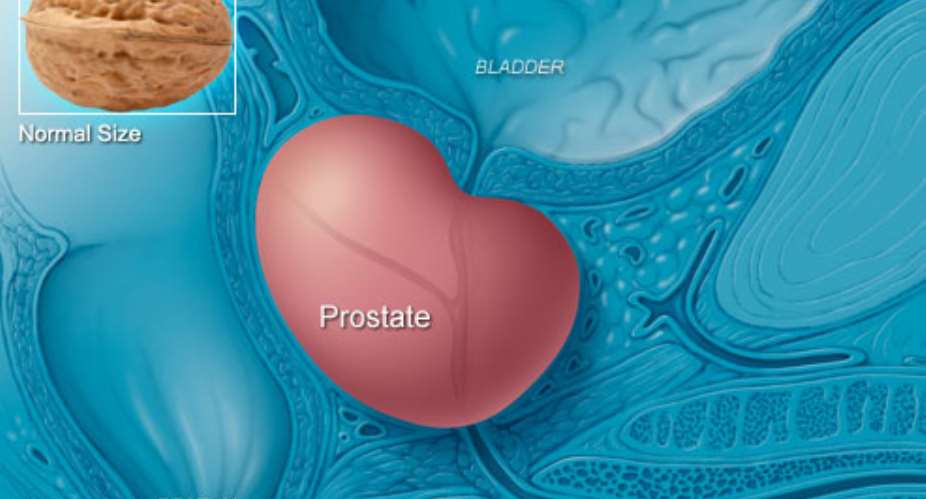

Your prostate gland labors in obscurity. The size of a golf ball, it's tucked away under your bladder, biding its time until you and your reproductive system decide to emit the sacred seed. Then the semen assembly line kicks in: The sperm swim up from your testicles to the seminal vesicles, and there they are mixed in a happy bath of fructose, vitamin C, and prostaglandins. This brew then proceeds to your prostate, which tops it off with enzymes, citric acid, and zinc before your man milk is propelled out of your body and into hers with rather pleasant smooth-muscle contractions. This long bomb triumphantly delivers your DNA into the end zone.

Ah, glory days.

But around the time in your life when you start to think more about your 401(k) than foreplay, your prostate starts to misfire. It swells in size, and the swelling clamps your urethra in a vise grip. If the cause of the swelling is benign, you're lucky. That's what those running-to-the-men's-room commercials for Flomax are all about. But some of the very same symptoms can also be caused by a prostate-cancer tumor.

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men; only some skin cancers are more rampant. In 2009, it caused an estimated 27,360 deaths—long, slow, embattled deaths, as the cancer spread beyond men's prostates to nearby bones, notably their spines. Once the cancer advances past your prostate, you have only a 30 percent chance of surviving 5 years. But catch it early, before the cancer cells escape, and your chance of surviving 5 years is 100 percent.

Here's the good news about prostate cancer: Deaths are down because it is being diagnosed much earlier. In fact, 94 percent of all diagnoses these days peg the malignancy at stage I or stage II, before it metastasizes beyond the prostate. (Stage III cancers have begun to break out of the prostate; stage IV cancers have invaded nearby tissue and bone.) That has resulted in a steadily declining death rate of 4 percent a year since 1994. The declining mortality has generally been attributed to the widespread use—starting in the 1990s—of a simple test for the prostate-specific antigen, or PSA.

THESE DAYS, THE PSA TEST IS SO ROUTINE for middle-aged men that your doctor might order one for you without even asking. My internist did that for me in the summer of 2007, as part of a regular physical. Mostly he was worried about my cholesterol levels. The results showed mildly troubling cholesterol—but a very troubling PSA number. Standards in place at the time held that it should be less than 4; some evidence has suggested that it should be less than 2.5 if you're younger than 50. Mine was 12.6.My doctor sent me to a urologist, who suspected that my high number was caused by a prostate infection. The only way to confirm those suspicions, unfortunately, was by collecting some prostatic fluid. He sat there grinning apologetically as he held up one gloved and well-lubricated index finger and asked me to bend over a chair. Then he stuck his finger up my ass and pushed on my prostate like it was a doorbell on Halloween night. About 10 minutes later, after I'd recovered, he gave me a scrip for an antibiotic and told me to come back at the end of the summer so he could retest my PSA.

I really didn't want to go back. So I didn't.

I put it off repeatedly until the night, months later, when I met the person I later called, only half jokingly, the Angel on the Train. I was sitting in the dining car having chicken a la Amtrak with my wife and son when suddenly a disheveled old man tottered up the aisle carrying a little plastic bag full of pills. The steward swung him around and plopped him into the booth with us. Nobody said a word for 15 minutes. Awkward! Then I started talking to him, and before I knew it we were comparing prostates. My wife ratted me out: "He had a high PSA reading," she said, waving her fork in my direction. "But he won't go back to the doctor."

The old guy turned to me. And, establishing eye contact for the first time, he said, "You really need to have that checked out."

When I returned home I had another PSA test. It was 9.2. That's better, right?

Well, as it turns out, nothing about the PSA test is accurate, starting with the name. The letters stand for a protein produced by the prostate. When PSA was first identified, the prostate appeared to be its only source, but it has even been detected, albeit in smaller amounts, in women. Clearly, there are non-prostate sources of PSA.

When your prostate is healthy, PSA is mostly contained within it, but if there is trouble in the tissue, more PSA can leak into the blood. By the time cancer has ransacked and spread beyond the gland, PSA levels can soar into the thousands. But the PSA test is so exquisitely fine-tuned that it picks up leaking PSA at the very lowest levels, measuring it in nanograms per milliliter of blood. That's right: nanogram, as in one-billionth of a gram.

As it turns out, the common threshold of 4 nanograms per milliliter is rather arbitrary. You can have cancer even if your PSA reading is below 4. That was definitively shown by a 2004 study of 2,950 men who were followed for 7 years as part of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. These men never had a PSA level above 4, or an abnormal digital rectal exam, for the entire length of the study. They all underwent a prostate biopsy—and cancer was found in 449 of them, or 15.2 percent.

On the other hand, you can have a PSA reading above 4, and it could be caused by two common maladies: prostatitis, which is an inflammation usually caused by an infection, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which is the fancy name for the benign swelling that plagues aging glands. Both can cause PSA leakage. In fact, the majority of high PSA readings are due to these noncancerous causes. Only one man in four with a PSA level between 4 and 10 will be found to have cancer after a subsequent biopsy.

So what good is this PSA test, anyway? Even its defenders admit, sheepishly, that it's no pregnancy test. And its detractors say it's useless. In 2004, a team of Stanford urologists looked at pathology results of more than 1,300 surgically removed prostates and found that the PSA number predicted nothing more than the gland's size. The lead author, Thomas Stamey, M.D., now retired, declared at the time, "The PSA era is probably over." Which is noteworthy: Dr. Stamey is one of the inventors of the method used to prepare PSA for testing, and in 1987 he published the first study linking increased PSA levels to prostate cancer.

But nobody listened, and a lot of men continue to get biopsies they don't really need. If an estimated 192,280 men were diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2009, you can bet another 575,000 men endured biopsies that turned up nothing. If that statistic makes you shrug, you've never had a doctor come after you with a biopsy gun. APRIL 11, 2008. I'M LYING on my left side on a gurney in my urologist's office. As instructed, I've lowered my pants to my knees. I'm here for a biopsy, but first comes the ultrasound. My doctor lubricates the ultrasound wand, which is about the size of my son's Spider-Man toothbrush, and slides it into my rectum. All is well until he starts to muscle it into various positions to improve the camera angles; then it feels less like a medical device and more like a broom handle.

Can a biopsy be any worse? Yes, it can. He inserts a syringe into my rectum to inject lidocaine into my prostate—six shots, in six separate locations, and all I can say is, never have a prostate biopsy without serious sedation. But by the time my doctor goes back up there to grab his 12 tissue samples, I don't feel a thing. I just hear the spring-loaded biopsy gun go off, bang, each time.

Then I go home to rest. And hope. Only a one in four chance they'll find something. I like those odds.

Five days later, the report comes back. Two of the 12 tissue cores are positive for cancer. I talk to people, even though the last thing I want to do is talk to people. Why are women so much better at this? They have "races for the cure" and that pink ribbon. A freakin' logo for their cancer! It must be a girl thing.

As for me, I just quietly call some strangers whose names have been passed along to me—by women, of course. One guy, John, had a biopsy that came back with only 1 percent cancer in one core. But his father had died of prostate cancer, so after 2 years of "watchful waiting," he finally went under the knife. I could opt for watchful waiting, but . . . waiting for what? For cancer to colonize my spine?

I have three treatment options: (1) surgery to remove my prostate, (2) external beams of radiation, or (3) brachytherapy, which involves implanting radioactive pellets in my prostate. Radiation treatments and their side effects can stretch out over months. I just want this to end. I'm in my 50s, so I'll recover from surgery, no problem. I choose surgery.

Besides, some 75,000 radical prostatectomies were performed robotically in the United States in 2008. The surgeon sits across the room at a console that looks like a video-game booth, manipulating a set of robotic arms over the patient. Unlike traditional surgery, there's no 8-inch incision and not as much blood loss; instead, the procedure is done through six dime-sized cuts in and below the navel. The best part, of course, is that the surgeon can be incredibly accurate, because he's seeing the tissues magnified 10 times and controlling the arms to make microsized movements. And if he sneezes, hey, no problem! As two doctors wrote in the British medical journal The Lancet, a nice feature here is the "elimination of a surgeon's physiological tremor."

Oh, yeah. I like that feature. When the whole point is to remove my prostate while sparing the surrounding nerves that create my erections, I totally love that feature.

It's June 18, 2008, two nights before surgery. I'm in bed with my wife, and I miss my prostate already. I tell her that if and when we have sex again, there will be no ejaculate, no man milk, no wet spot. Henceforth I shall be seedless. You can see where I was going with this, can't you, guys? I was hoping I'd receive a happy send-off.

My wife says, "You should talk to your doctor about that."

Gosh, honey. Thanks.

HERE'S WHAT PATIENTS THINK THEIR doctors say: If you undergo the relatively new "nerve-sparing" prostate surgery, you will eventually return to the level of erectile function you enjoyed before you had the surgery. It may take weeks, months, or a couple of years, depending on age and prostate size—but that mojo will return. That's what patients want to hear, too, so maybe they miss the doctors' qualifiers about "most men," and "in certain cases..."

Unfortunately, that's just not the truth, says John L. Gore, M.D., an assistant professor of urology at the University of Washington. "Even with a perfect surgery there's going to be some shutdown."

Dr. Gore is qualified to say this; he conducted one of the most recent studies of prostate-cancer patients and how surgery affects them. He and his UCLA colleague, Mark Litwin, M.D., followed 475 prostate-cancer patients for 4 years. These patients received more scrutiny than the typical sohow's-your-erection questions from their doctors. They filled out a 20-minute questionnaire in the privacy of their homes before surgery and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, and 48 months afterward. And, no, things were not as they had been before."We're not saying sexual function is terrible after surgery," says Dr. Gore. "We're saying the likelihood of that function being exactly what it was before surgery is essentially zero." And, he adds, you'll recover what you're going to recover within 2 years. "Beyond that, it is what it is."

NDC demands complete overhaul of security protocols at EC to safeguard electoral...

NDC demands complete overhaul of security protocols at EC to safeguard electoral...

Ghana reaches interim deal with international bondholders — Finance Ministry

Ghana reaches interim deal with international bondholders — Finance Ministry

Mahama to form joint army-police anti-robbery squads to safeguard 24-hour econom...

Mahama to form joint army-police anti-robbery squads to safeguard 24-hour econom...

Another man jailed eight months over shrinking penis

Another man jailed eight months over shrinking penis

Ghana to adjust external bond deal to meet IMF debt sustainability goals — Finan...

Ghana to adjust external bond deal to meet IMF debt sustainability goals — Finan...

IMF negotiations: We've not failed to reach an agreement with bondholders; we’ve...

IMF negotiations: We've not failed to reach an agreement with bondholders; we’ve...

EC begins recruitment of temporary electoral officials, closes on April 29

EC begins recruitment of temporary electoral officials, closes on April 29

NPP lost the 2024 elections in 2022 due to inflation and cedi depreciation — Mar...

NPP lost the 2024 elections in 2022 due to inflation and cedi depreciation — Mar...

Your good heart towards Ghana has changed; don’t behave like Saul - Owusu Bempah...

Your good heart towards Ghana has changed; don’t behave like Saul - Owusu Bempah...

Wa West: NDC organizes symposium for Vieri Ward Women

Wa West: NDC organizes symposium for Vieri Ward Women