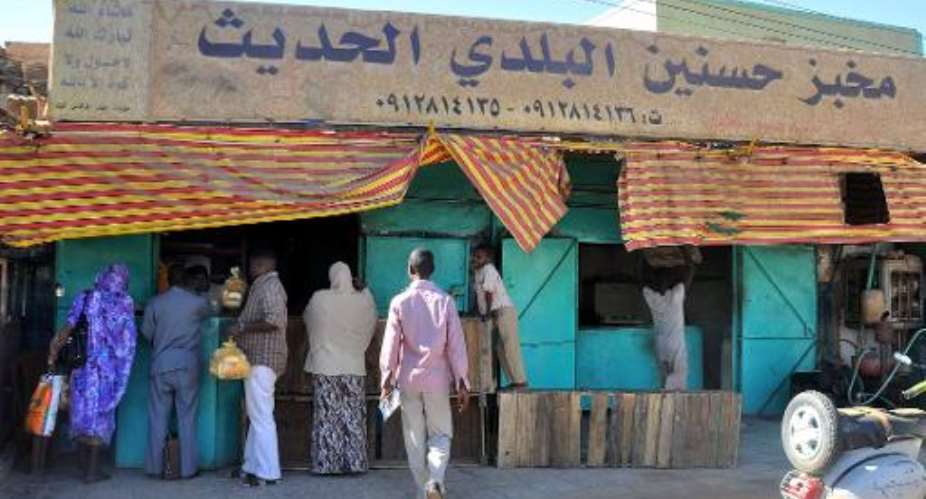

Khartoum (AFP) - Sudan battled a politically explosive bread shortage Tuesday that has forced Khartoum residents to wait hours for the staple food because a lack of foreign exchange is limiting wheat imports.

AFP reporters saw lines of seven to 20 people at Khartoum-area bakeries on Tuesday, about three days after shortages began.

"Today our production was 50 percent of normal," Adam Mohammed, a baker in North Khartoum, said Tuesday night as several people waited for their loaves.

But Mohammed said he expected the supply of flour to improve from Wednesday.

Vice President Ali Osman Taha has ordered officials to ensure that enough wheat reaches the flour mills, the state news agency SUNA reported.

Khalifa Hassan, a government worker queueing at a neighbourhood bakery in North Khartoum on Monday, had said that "if this continues, people will not keep silent."

"For the past three days I have to spend two hours a day waiting for bread, one hour in the morning and one in the evening."

An analyst said the government seems hesitant to allow a further increase in bread prices because it fears more anti-regime demonstrations after the slashing of fuel subsidies in September led to protests in which dozens died.

"Politically, this is more sensitive than removing the subsidies from petroleum products," said Safwat Fanous, a University of Khartoum political scientist.

The price of bread, generally sold in flat, round loaves, had already gone up several days ago by roughly one-third. One Sudanese pound (about 17 US cents/13 euro cents) now buys three loaves, against four earlier.

The minimum wage for a civil servant is officially only 425 pounds a month, but much more than that is needed for a family to get by, at least in the cities.

"This has increased our suffering," Osman Siddiq, a resident of North Khartoum, complained while waiting for fresh loaves.

Sudan does not grow enough wheat to fulfil its needs.

The government subsidises the rate at which wheat importers obtain hard currency to buy the grain from Canada and other countries, said Fanous.

And the central bank, facing a shortage of hard currency, has not been able to provide enough dollars to import sufficient quantities of grain, meaning mills "don't have enough wheat," Fanous said.

Khartoum lost billions of dollars in export earnings when South Sudan became independent in 2011, taking with it most of Sudan's oil production.

Since then Sudanese have endured two years of rising prices and a sinking pound.

On the widely used black market the local currency has lost almost 50 percent of its value over the past two years.

Inflation officially reached 40 percent last month.

Fuel prices rose by more than 60 percent in September when the government drastically reduced subsidies as part of measures to stabilise the economy.

Thousands of people, many of them Khartoum-area poor, took to the streets in protest and called for the downfall of President Omar al-Bashir's 24-year regime.

Security forces are believed to have killed more than 200 demonstrators, Amnesty International said, but authorities reported a toll of less than half that.

The rising fuel prices have also pushed up transportation and cooking costs for bread manufacturers, said Imam Omar, a baker.

"Because of this we had to increase the price," he said.

On top of that, flour manufacturers have not been able to provide the same quantities to the bakeries.

"We used to get 30 sacks a day. Now they only give us 15 sacks," Omar said.

In early September a senior ruling party official said the regime planned to lift the wheat subsidies, but Fanous said that now seems too politically dangerous.

Although rural Sudanese depend on sorghum, most city people rely on bread. If the price goes up, "more and more people will become hungry," creating a potential for unrest, Fanous said.

"Of course, political trouble comes from the cities," he said.

"The government, on the other hand, is under pressure from the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and other financial institutions to remove subsidies."

After meeting with Taha and other officials on Tuesday, State Minister of Finance Magdi Yasin said wheat imports "will continue, in coordination with the central bank and ministry of finance."

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...