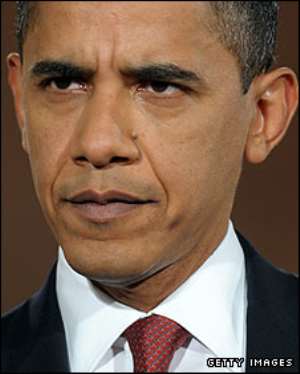

South Sudan's independence referendum on Sunday marks the start of a new test for U.S. diplomacy in the region, which analysts say could yet present President Barack Obama with his "Rwanda moment" if violence explodes in its wake.

U.S. officials are cautiously optimistic about the vote, which is expected to see southern Sudan opt to split off as an independent country in the last step of a 2005 peace deal that ended one of Africa's bloodiest civil wars.

"The six months after the referendum are the most dangerous," said John Prendergast of the anti-genocide Enough Project who in July warned that Obama faced a "Rwanda moment" similar to that confronted by former President Bill Clinton.

Clinton has said his main regret as president was failing to prevent the slaughter of 800,000 people in that conflict.

In Sudan, a credible referendum would be welcome news in Washington, which has ramped up pressure in recent months, seeking to head off hostilities between the central government in Khartoum and south Sudanese leaders in Juba.

But officials are less confident about the next phase, a tricky six-month transition as the two countries separate, and how Washington can help to ensure peace between two sides long divided by religion, ethnicity, ideology and oil revenues.

Crucial issues including borders, citizenship, and division of Sudan's oil revenues are yet to be decided, any of which could trigger bloodshed that some warn might potentially rival the 1994 genocide in Rwanda if it expands into full-blown war.

"The U.S. will play a major role in whatever the outcome is. With intelligent, principled policies, along with personal engagement, President Obama can help make the difference between war and peace in Sudan," Prendergast said.

Obama has stressed his personal interest in Sudan, but for the first year of his administration the policy seemed adrift as various U.S. officials advocated different strategies.

Obama's Sudan envoy, Scott Gration, worked to improve links with the government of President Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes and genocide connected to the violent suppression of a revolt in the western region of Darfur beginning in 2003.

Critics charged Gration was too soft on Khartoum -- which remains under U.S. and U.N. sanctions -- and predicted trouble for oil-producing southern Sudan if it voted to secede.

In mid-2010, however, Washington dramatically increased its involvement by offering Khartoum new incentives, including eventual normalization of U.S. ties if it allowed the vote to go ahead, and dispatching a retired diplomat, Princeton Lyman, to personally shepherd talks between the North and the South.

"The administration sees this as a prevention situation. They feel that aggressive action beforehand can head off very costly violence in the future, "said Michael Abramowitz, director of the Committee on Conscience which guides genocide prevention efforts at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

A DIFFICULT ROAD

With Bashir pledging to respect the outcome of Sunday's referendum, U.S. officials say the diplomatic investment is paying off -- at least so far.

"We believe that the right signals are being sent, both in North and South, in terms of the upcoming referendum and respecting the results," State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley said, while acknowledging "a difficult road ahead" to resolve the outstanding differences between the two sides.

Jennifer Cooke, director of the Africa Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, said the United States faced huge challenges in bridging the remaining gaps between the two sides, particularly on the disputed oil-producing region of Abyei, which many fear represents one of the chief threats to lasting peace.

"There's a tendency in some constituencies to overestimate U.S. leverage over the situation, saying this could be Obama's genocide, Obama's Rwanda, and that this is the Obama administration's to lose," Cooke said. "We have to be somewhat modest about what the U.S. can and cannot do here."

The United States must maintain a united international front, particularly among Sudan's neighbors, to ensure that the existing agreements are carried out peacefully while working out the mechanics of how Africa's largest country will divide following the expected secession vote.

"I think we'll muddle through the vote, and there will be a tendency in the media to say that the referendum was a success. That would be unfortunate and wrong because the real hard work will be in the next six months," said Richard Williamson, who was the Sudan envoy under President George W. Bush and is now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Williamson said the Obama administration, which has thus far emphasized rewards for Khartoum's good behavior rather than potential punitive measures for bad, may need to underscore the costs of any backsliding.

"You have to have real diplomacy, and incentives (alone) are not real diplomacy," Williamson said. "They need to have a much more traditional and realistic negotiating posture, and discuss the full range of severe constraints they might face."

Akufo-Addo spotted ordering chiefs to stand for his handshake

Akufo-Addo spotted ordering chiefs to stand for his handshake

Akufo-Addo ‘disrespects’ every chief in Ghana except Okyenhene — NDC Communicato...

Akufo-Addo ‘disrespects’ every chief in Ghana except Okyenhene — NDC Communicato...

Supreme Court clears way for dual citizens to hold key public positions

Supreme Court clears way for dual citizens to hold key public positions

Be transparent, don’t suppress the truth – Prof. Opoku-Agyemang to Jean Mensa

Be transparent, don’t suppress the truth – Prof. Opoku-Agyemang to Jean Mensa

‘I won’t tell the world I was only a driver’s mate during challenges’ – Prof Jan...

‘I won’t tell the world I was only a driver’s mate during challenges’ – Prof Jan...

We’ll prosecute corrupt officials of Akufo-Addo’s govt – Prof Jane Naana

We’ll prosecute corrupt officials of Akufo-Addo’s govt – Prof Jane Naana

[Full text] Acceptance speech by Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as 2024 NDC Runn...

[Full text] Acceptance speech by Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as 2024 NDC Runn...

Election 2024: Don’t be complacent, we haven’t won yet – Asiedu Nketia cautions ...

Election 2024: Don’t be complacent, we haven’t won yet – Asiedu Nketia cautions ...

Election 2024: Stop fighting over positions in Mahama’s next govt – Asiedu Nketi...

Election 2024: Stop fighting over positions in Mahama’s next govt – Asiedu Nketi...

Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang will restore dignity of vice presidency – Fifi Kw...

Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang will restore dignity of vice presidency – Fifi Kw...