This seems an unlikely place to go fishing for your dinner. The dusty scrublands of Zomba West have been brittle dry since April, when the rainy season ended.

The place is spookily deserted today - the funeral of the local chief. In the marketplace, we find only one stall open, run by children. And all they are selling is fish.

"When we first started fish farming - people thought it was mad - they told us it will never work here," says Esther Fikira.

She leads me to a series of dirty green ponds, dug into the baked clay soil.

The water is murky, almost stagnant, but Esther assures me there is a big haul of tasty "chambo" (a local delicacy) lurking just below the surface.

"If you had only seen the benefits this community has had from eating these fish," says the 50-year-old, wading in, "then you will know why I will never give my pond away."

Dry county

There are now 700 fish farmers like Esther here in the bushland settlements to the west of Malawi's former colonial capital, Zomba.

You may have heard of the fiction novel Salmon Fishing in the Yemen. Well, this is the real thing - an ambitious food security project developed by the WorldFish Centre, a member of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR).

They are introducing small-scale aquaculture to ensure families in Malawi have enough food and income to buy maize - even in years when droughts affect their crops.

The project assists farmers by digging small, rain-fed ponds of about 10x15m on their land, or anywhere the soil is suitable for retaining water.

Families like Esther's use the ponds to rear common fish species - which in Malawi means chambo (a species of tilapia) and kampango (catfish).

At WorldFish's local headquarters, just along the road, Dr Daniel Jamu and his team of scientists are breeding new varieties of chambo - selected to grow fast, fat, and feed happily on whatever waste is left over from households.

Esther uses manure from her goats and chickens to keep the pond high in nutrients which allow plankton to thrive. The fish eat the plankton, and when they grow to full size, they are harvested, usually every six months.

Trading up

She sells most of her fish - raising enough money to buy maize when the harvest is poor, and to help feed and clothe the orphaned children she takes in.

"Before we had the ponds, this area suffered from a lot of poverty," she explains. "We didn't eat meat, and we lacked any source of income.

"But with the coming of the fish ponds, we had so much leftover to sell, I had enough money left over to buy fertiliser, with the government subsidy."

When the ponds are emptied, a rich layer of silt can be dug from the base - to use as fertiliser. Esther uses hers to grow maize, which in turn ensures that her goats and chickens keep popping out manure for the pond.

It's a perfect circle. "Or what we call an integrated agriculture-aquaculture (IAA) system," says Joseph Nagoli, of WorldFish. "This isn't high input fish farming. This is simple and sustainable."

Previous attempts to introduce aquaculture in Malawi have failed, he says, "because people though there was no longer need to grow maize. The message was wrong. Now we see fish is just one part of a family's agriculture".

Their latest research project aims to quantify the nutritional value of different species of tilapia

Healthy harvest

The fish supply essential protein, calcium, and vitamin A - essential for children and the elderly, and those with HIV/AIDS.

Almost one fifth of Malawians aged 15-49 are infected, and each year tens of thousands die of the disease.

But good nourishment can prolong the life of HIV/AIDS patients by up to eight years, according to research by the World Health Organisation.

WorldFish has introduced aquaculture to 1,200 HIV affected families in Malawi - doubling their average annual income and increasing their intake of fish by 150%.

Esther has already seen the impacts first hand.

"The nutritional impact of the fish was very obvious - on the children, the elderly, and most especially on those with HIV/AIDS," she says.

"I have a neighbour who was very sick. Now she is able to work in the fields - to make a living."

The challenge now, says Nagoli, is to expand aquaculture from "a sector to an industry". WorldFish has a target of 8,000 households in Malawi - equivalent to 40,000 people.

Fortunately, there is already a healthy appetite for fish among the country's 11 million population. Malawi may be landlocked, but it has had a thriving fishing industry, based largely in Lake Malawi and Lake Chilwa.

"It may surprise you to know, that the biggest source of protein for Malawians is not chicken or beef, but fish," says Dr Jeffrey Luhanga, technical controller of Malawi's Ministry of Agriculture.

"We have a policy - a fish every day."

But just as staple crops are under threat from climate change and over-intensive farming practices, so to is Malawi's fishing industry.

Out of stock

Lake Chilwa provides around 20% of the country's catch - 17,000 tonnes - but at a depth of just 7m, it is highly vulnerable to drought - having completely dried up as recently as 1995.

"Nobody knows what will happen with climate change," concedes Mr Nagoli.

Meanwhile, the lake's fish stocks are already suffering from over-fishing and environmental degradation.

The lake's resident population of fishermen - who live in floating reed huts, on the marshy shorelines of Chisi island - are watching their livelihoods evaporate.

As dusk falls, I cross to the island by motor boat, weaving through the reeds, until we find a fire alight in one of the floating huts.

"The catch is not good," says Mr Irons - an elderly veteran, who uses traps to catch his tilapia. "The other fishermen use nets, and they are taking all the catch. I get bigger fish, but I don't get as many."

He worries for his family. They live miles away and he sees them very rarely. If the stocks dry up, he won't have any income to support them.

WorldFish are working to introduce sustainable fishing practices - to ensure the survival of both the fish and the fishermen.

"Urban" fish farming could be the key to their success in the longterm - by easing the burden on Lake Chilwa's precious natural resources.

"You know the old saying," says Dr Luhanga. "Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day.

"Teach him how to fish and you feed him for a lifetime."

By James Morgan

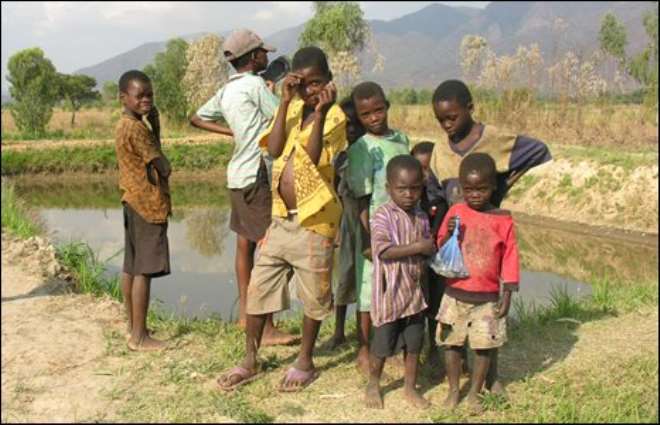

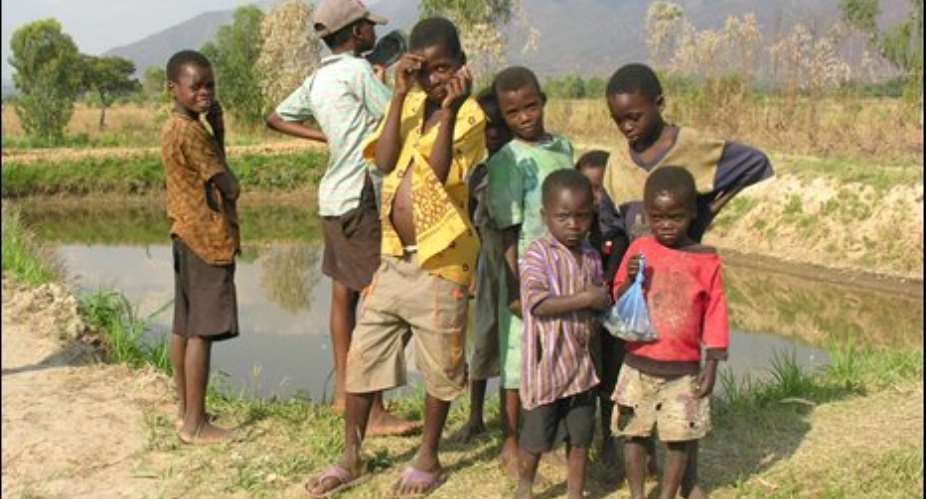

Fish farmed in these ponds help keep the children of Zomba West healthy

Fish farmed in these ponds help keep the children of Zomba West healthy

Esther Fikira weeds out one of her fish ponds, in West Zomba

Esther Fikira weeds out one of her fish ponds, in West Zomba

Fish are now a source of income for families in West Zomba

Fish are now a source of income for families in West Zomba

Silt from the fish ponds is used to keep soils fertile for crop planting

Silt from the fish ponds is used to keep soils fertile for crop planting

Daniel Jamu oversees tilapia breeding at the WorldFish research centre

Daniel Jamu oversees tilapia breeding at the WorldFish research centre

Fishermen of Lake Chilwa

Fishermen of Lake Chilwa

Whoever participated in the plunder of the state must be held accountable – Jane...

Whoever participated in the plunder of the state must be held accountable – Jane...

A vote for John and Jane is a vote to pull Ghana from the precipice of destructi...

A vote for John and Jane is a vote to pull Ghana from the precipice of destructi...

I’ll repay your abiding confidence with loyalty, understanding and a devotion to...

I’ll repay your abiding confidence with loyalty, understanding and a devotion to...

‘I’ve learnt deeply useful lessons for the future' — Serwaa Amihere breaks silen...

‘I’ve learnt deeply useful lessons for the future' — Serwaa Amihere breaks silen...

I’m sorry for the embarrassment – Serwaa Amihere apologises for leaked sex video

I’m sorry for the embarrassment – Serwaa Amihere apologises for leaked sex video

Dumsor: Matthew Opoku Prempeh not in charge of Energy sector – Minority

Dumsor: Matthew Opoku Prempeh not in charge of Energy sector – Minority

Adu Boahen’s murder: Police arrest house help who was in possession of deceased’...

Adu Boahen’s murder: Police arrest house help who was in possession of deceased’...

Akufo-Addo nominates Felicia Attipoe as Tema West MCE

Akufo-Addo nominates Felicia Attipoe as Tema West MCE

Election 2024: I can't have someone I defeated twice as my successor – Akufo-Add...

Election 2024: I can't have someone I defeated twice as my successor – Akufo-Add...