Early in May 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron raised the possibility of a new type of political community that would enable countries outside the EU sign-up to "European core values”.

He said that this would enable the "European political community" to open up to democratic European nations that do not belong to the European Union (EU).

The new community, he said, would include those that adhere to the core values of the EU in areas such as political cooperation, security, cooperation in energy and – most importantly – the circulation of people.

Macron was talking in Strasbourg before the closing session of the Conference on the Future of Europe and the release of its report with proposals for reform.

The timing of his address on Europe Day - 9 May - in what is often known as Europe month is significant and the irony will be missed on few observers of European development and expansion.

Ukraine in Europe?

As it stands, Britain has already pulled out of the European Union entirely while Ukraine is facing the onslaught of Russian military might using weapons supplied partially by the EU.

"Ukraine by its fight and its courage is already a heartfelt member of our Europe, of our family, of our union," Macron said in his address.

"[However] Even if we grant it candidate status tomorrow, we all know perfectly well that the process to allow it to join would take several years indeed, probably several decades."

Rather than bringing down stringent standards to allow countries to join more quickly, Macron suggested creating a parallel entity that could appeal to countries who aspired to join the bloc or, in an apparent reference to Britain, countries that had left the union.

"Even if we grant it candidate status tomorrow, we all know perfectly well that the process to allow it to join would take several years indeed, probably several decades,” Macron added.

Maastricht principles

Those standards were outlined seven decades ago in the creation of a trade bloc known at the time as the European Economic Community (EEC).

The European Economic Community was a regional organisation that aimed to bring about economic integration among its member states. It was created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957. Upon the formation of the European Union in 1993 with the Maastricht Treaty, the EEC was incorporated into the EU and renamed the European Community

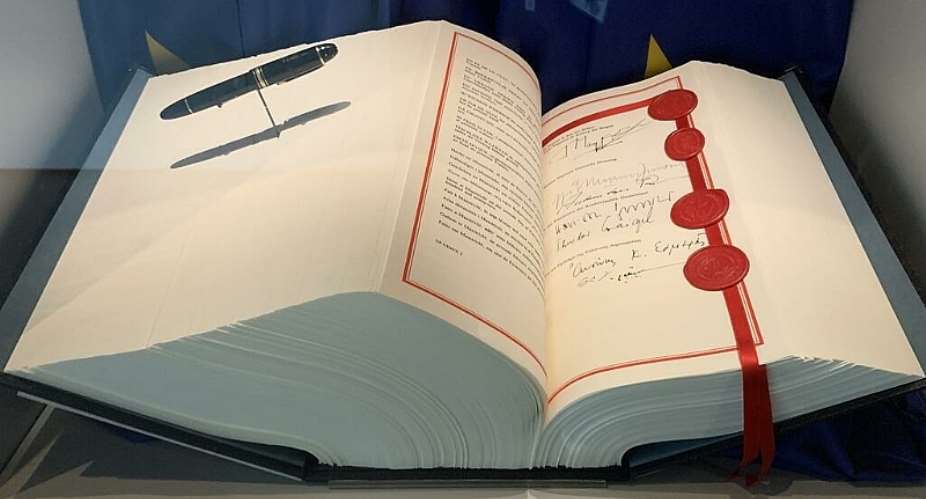

The Maastricht Treaty laid down the foundations for the European Union. The treaty was signed by twelve countries in the Dutch city of Maastricht in 1992 and went into effect in 1993.

The agreement established greater cooperation between member states through economic, social and legal channels.

The Maastricht Treaty, or to give it its full title, the Treaty on European Union, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU) and, according to the signatories, was the first step in "a new stage in the process of European integration".

It also foresaw a shared European citizenship, the eventual introduction of a single currency, and the development of a common foreign and security policy.

Although these were widely seen to presage a "federal Europe", the focus of constitutional debate shifted to the later 2007 Treaty of Lisbon.

The emergence of the European Union

However, the emergence of the European Union was not just the product of the Maastricht Treaty, but the product of two other events that followed each other in rapid succession, notably the unification of Germany and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Olivier de France, a senior research fellow at The French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs, told RFI.

“The European Union, which at the time was not yet the European Union, but which was in the process of becoming the European Union, stemmed from these three events [Masstricht, German unification, collapse of the Soviet Union],” he said.

“On the one hand economic consolidation - because the Maastricht Treaty is the moment when Europe completes the internal market - on the other hand there is freedom of movement of people, goods, and services and so on.”

The third is a direct result of the Maastricht Treaty which led to the creation of the internal market, which in turn prefigured the completion of the monetary union and therefore the euro, which will arrive a little later in the decade, he added.

He also points out that these laid the groundwork for political unification where the existing members transformed from the European community into the European Union.

The Maastricht Treaty also laid the foundations for a common foreign and security policy and is based on three ideas. On the one hand, it is Montesquieu's idea of 'soft' commerce, or the notion that through trade and through the economy, we can decrease violence, including open warfare, de France explains.

“On the other had, you have the political side [of this] and you have the emergence of an “ever closer union of the European peoples,” he added.

“[Thirdly] On the strategic side, you have the project of perpetual peace, which is a Kantian project. So, together, you have Montesquieu Maastricht and Kant.”

The Need For Change?

However, it is clear that more is needed. The Secretary General of the Council of Europe, Marija Pejčinović Burić marked Europe Day 2022 by calling on European states to renew their investment in human rights, democracy and the rule of law in the face of “terrible violence and seismic change”.

Launching her annual report, Moving Forward 2022, she condemned Russian aggression against Ukraine and praised the “grit, bravery and determination” of the Ukrainian people.

“We had dared to believe that pictures like this – realities like this – belonged to Europe's past. We were wrong. History has returned to our continent in the cruelest of ways,” she said.

More broadly, she added that this is a warning to all of us. What has happened once could happen again. The success of our multilateralism rests on the determination of governments to ensure that their citizens' fundamental rights are interwoven with every aspect of life on our continent.

However, she is not the only one that believes change, or an extension of the treaties that established the European Union is necessary.

On Europe Day, the European Parliament endorsed a rewrite of the treaties, distilling 300 recommended changes formulated by the Conference on the Future of Europe citizen consultation, into 49 proposals.

EU officials said the list of proposals will be assessed, but that it is too early to say whether any of those retained would require a full treaty overhaul.

However, if a majority of EU member states decided treaty change was needed, there could be a vote in the European Council that would lead to negotiations.

The UK Exception

Clarification and change do not necessarily mean something new unlike the case of the UK when it voted to leave the EU in 2016 in what became known as Brexit. However, Olivier de France points out that the signs of problems in the relationship with the EU go a long way back and are not necessarily a reaction to the Maastricht Treaty.

In fact, he argues that the whole history of the UK's relationship with the continent is littered with “troubled” moments.

"Whether it is Labour wanting to leave the European Community in 1974 just after joining, or whether it is 1985 when the UK doesn't join Schengen, or whether it's Margaret Thatcher's 'I want my money back' or whether it's the decision not to join the euro," he said.

Most recently, the defense agreement between the UK, Australia and the US, which provoked strong reactions in France, is telling.

“It remains a moment of contemporary clarification. Because we have the impression that on the European side, we are going to try to consolidate ourselves from a political and strategic point of view to create strategic autonomy,” he said.

“On the other side, you have the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia in a kind of alliance of democracies that will face-up to more brutal actors on the international scene, like Russia or like China.”

This is why Maastricht in 1992 is an important date. From Maastricht onwards it became clear that Europe was moving in a direction that the UK did not want to go.

De France added: “The United Kingdom, in fact, ever since it joined the European Economic Community in 1973, has wanted a commercial and economic union that went in a direction that suited the United Kingdom's economic interests.

A federal Europe?

In 2022, do we need to choose between a Europe of Nations and a federal Europe and what kind of a Europe will it be? In terms of identity, for example, how do you resolve the dichotomy between the national elements of the EU and the federal elements? Is it necessary to rethink European identity?

"From the point of view of identity, what you mention - the sort of dichotomy between the national aspect and the federal aspect - you need to try to rethink European identities," he said.

De France believes the two, however, are not mutually exclusive. He sees the EU as a palimpses where information and ideas are added and superimposed on the original page.

In 1992, he points out, it was easier to feel that you could be Catalan, Spanish or European. Today, these diverse types of identity tend to exclude each other more than they reinforce each other.

Change is happening at a basic level, however. “I think that today, when we are faced with global ecological and strategic changes the starting point is ourselves, then our city, then our country, then Europe and then the world,” he added.

However, he believes that European should do the opposite. “Start from the changes in the world and define yourself in relation to them, rather than defining the changes in the world in relation to yourself,” he added.

Conference on the Future of Europe

The citizens' conference underlines this. The two-year consultation involved 800 EU citizens selected randomly, but balanced for gender, age, education, and socioeconomic levels who all looked at ways the EU works and what it could do better.

It produced 325 measures and 49 prospasals on the future of Europe published at the beginning of May 2022. If adopted in their entirety is likely that it would entail an overhaul of how the EU currently takes policy stances and decisions.

Among them is the proposal to get rid of the need for unanimous agreement by all 27 EU countries in sensitive areas such as taxes, social security, foreign policy and accepting new members.

Another would empower the European Parliament to put forward legislative proposals itself, instead of weighing initiatives made by the European Commission or, less commonly, the European Council, which represents member states.

Guy Verhofstadt, an MEP and former Belgian prime minister who chaired the citizen Conference on the Future of Europe, tweeted that the vote was an "ambitious implementation" of what had been urged.

"Health, energy, defence, democracy... Another EU is possible!" he said.

In a speech to MEPs before the initial proposals were published Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi addressed MEPs and argued that the EU needs to become "stronger" through "pragmatic federalism".

Russia's war in Ukraine, a country that hopes one day to join the EU, has shown the bloc's institutions to be inadequate in their response, he said. Draghi called for the European Union to adopt more streamlined decision-making, notably by doing away with the unanimity rule, and for it to expand eastwards, taking in Ukraine and Balkan nations.

While these proposals are a long way away from being implemented, they do demonstrate that the EU is dynamic despite its failings, as it has been since the signing of the Maastricht Treaty.

"I can now see clearly with my two eyes, thanks to the generosity of Afenyo-Mark...

"I can now see clearly with my two eyes, thanks to the generosity of Afenyo-Mark...

Amansie Central: Violent rainstorm causes havoc at Jacobu; one dead

Amansie Central: Violent rainstorm causes havoc at Jacobu; one dead

Renaming Ho Technical University after Ephraim Amu is illegal – Minority slams g...

Renaming Ho Technical University after Ephraim Amu is illegal – Minority slams g...

Gomoa Akotsi: Truck crashes into police vehicle, one dead, several officers inju...

Gomoa Akotsi: Truck crashes into police vehicle, one dead, several officers inju...

Election 2024: Power outages will affect NPP – Political scientist

Election 2024: Power outages will affect NPP – Political scientist

NPP is 'a laughing stock' for luring 'poster-stickers', 'noisemaking babies' wit...

NPP is 'a laughing stock' for luring 'poster-stickers', 'noisemaking babies' wit...

Dumsor: Matthew Opoku Prempeh must be removed over power crisis – IES

Dumsor: Matthew Opoku Prempeh must be removed over power crisis – IES

PAC orders WA East DCE to process requests from their MP

PAC orders WA East DCE to process requests from their MP

Defectors who ditched Alan’s Movement to rejoin NPP were financially induced – A...

Defectors who ditched Alan’s Movement to rejoin NPP were financially induced – A...

Dumsor: Akufo-Addo has taken Ghanaians for granted, let’s organise a vigil – Yvo...

Dumsor: Akufo-Addo has taken Ghanaians for granted, let’s organise a vigil – Yvo...