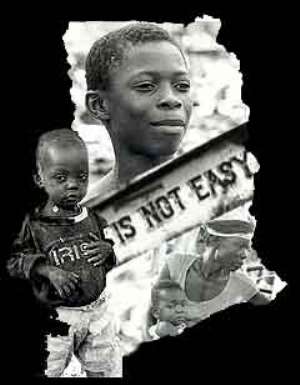

A tale of two countries: My motherland offers riches to the tourist, so why are so many Ghanaians queuing up to come to Britain? While my primary government, in London, has been struggling to persuade people in Britain it has done enough to keep out the huddled masses from eastern Europe, my secondary government, in Accra, has also been preoccupied with travel. But rather than keeping undesirables out, Ghana's government is more concerned with bringing people in: to spend their pounds, dollars and euros on business and tourism. And Ghanaians living in Britain are being asked to do their bit to help turn their country into Africa's number one destination. The tourism minister, Jake Obestebi-Lamptey, wants us to tell people that the former Gold Coast has become a "bird-watcher's paradise, eco-tourism haven and an adventurer's dream". I've been wondering, though, how we can persuade the locals that they are sitting on such a goldmine. Stroll past the British high commission in Accra on any given evening and you'll see Ghanaians bedding down, hoping to be the first in the visa queue the next morning. And the 35,000 Ghanaians who were granted short-term entry to Britain this year, and the similar number of rejects, are just a fraction of those who dream of fleeing poverty. With doctors, nurses and teachers in the vanguard, ministers have been insisting on loyalty clauses for ambitious graduates. Not for nothing are we called the "Jews of Africa", with an estimated 200,000 Ghanaians and their descendants settling in this country alone since independence. Some people are used to thinking of Ghana as a "beacon" country of stability and inward investment - the symbolic destination for African-Caribbeans and Americans who wish to reclaim their heritage. Didn't the IMF and World Bank lavish praise on former president Jerry Rawlings and his successor John Kufuor for their growth rates of 5%? Haven't Japan and the EU given Ghana millions of dollars for skills training and poverty reduction? Indeed they have. But when I visit my motherland this summer, it will, once again, be a tale of two countries. I'll marvel at the beach hotels, luxury estates and free press, and revel in the power of the pound, which takes me from bohemian Brixton to the elite of Ghanaian society in six hours. But this is the Ghana of the expatriate, and the rich business and political classes, who travel in and out of Britain, but have no intention of staying because their standard of living cannot be replicated in any European country. The other Ghana is that of my cousin, a pastor, who ministers in the densely populated areas of Greater Accra. Maamobi is typical; a district of shanty housing, open sewers, malaria and mass unemployment. If you are lucky enough to have a job, your minimum wage has just gone up to 11,000 cedis (65p) a day. My aunt is a typical resident, full of incredible hospitality, but she talks about her own future with little ambition, investing all hope in the children she's managed to send abroad. Swatting away flies under the burning sun, she chats about whether things can change in "Mother Ghana", with frequent references to gye nyame ("only God can help us"). Perhaps such fatalism is understandable in a 60-year-old, who has witnessed colonial rule followed by decades of strong-man politics. But it is more distressing to see the fight go out of younger people, who can spend years in limbo, waiting for an overseas relative to pay some middle man a £3,000 "connection fee" to ease their passage. Ironically these are the same Ghanaians who, once here, will hold down two or three jobs, and contribute their share of an annual $1.5bn in remittances to sustain their family. When cousins ask me how life is in Britain, I warn that although the 60s Nkrumah generation - which includes my parents - have largely succeeded in grooming their children for a middle-class future, things are more unpleasant for recent arrivals; that unless they have key qualifications (medical, educational or social work), they will have few choices - hence around 60% of London's parking attendants are Ghanaian or Nigerian. Perhaps naively I offer to help them do business locally alongside the mechanics, seamstresses and shopkeepers, who somehow manage to make ends meet, but then I hear of Ghana's frighteningly high interest and inflation rates, the soaring price of utilities (a consequence of foreign-inspired privatisation), and the stop-go electricity supply. If, like my uncle in Kumasi, you take up farming, which comprises 36% of Ghana's GDP, could you compete with cheap subsidised goods from the west, without being given access to European and US markets? Would you wait for change to be delivered by Blair and Geldof's African Commission? No, in those circumstances, £6 an hour as a security guard or a cleaner in a faraway country may sound like a better way to make money. Perhaps, like the dozens of others who'll be bedding down outside the British high commission tonight, you'd rehearse your lines in preparation for an interview, and perhaps a passport to life in London's underbelly. So, if you're a British traveller huffing at the occasional delay at Heathrow, spare a thought for the other kind of global traffic heading in your direction with tourism the last thing on its mind. Henry Bonsu is a journalist and broadcaster This article was published in the Guardian

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...