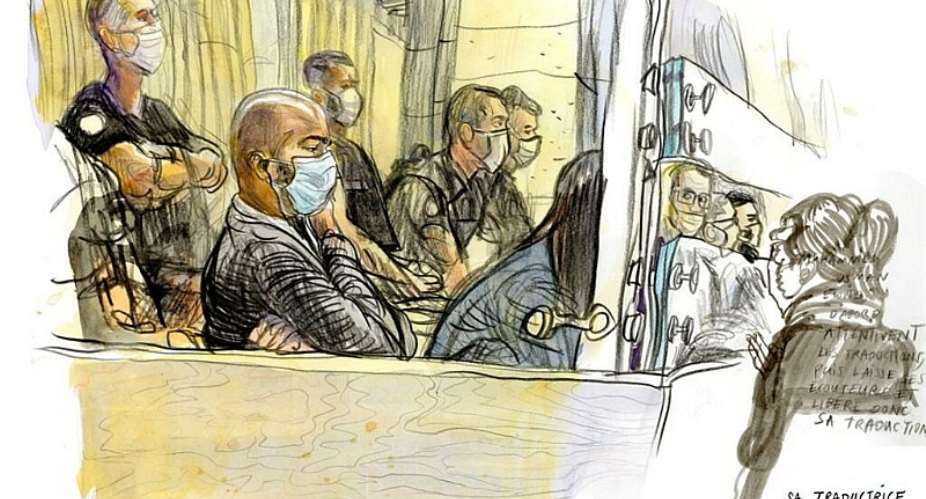

Following the second Covid-enforced adjournment of the year, the Paris attacks trial resumed on Tuesday with evidence from Muhammed Usman, one of the accused, on his religious background and his activities in the Syrian war zone. Nothing was terribly clear.

Usman's strategy is simple. Confronted with statements which might be unfavourable to himself, this Urdu-speaking Pakistani answered in monosyllabic French: "no" or "it's not true" or "I did not".

Given the chance to answer less damaging questions, or faced with his own contradictions, he made use of the court translator to offer long and not always clear explanations, sometimes in flat opposition to evidence he has already recorded in his various confrontations with the police, in Greece, Austria and France.

The broad lines of Muhammed Usman's story are, by now, well established.

Born in rural Pakistan, he spent six years in a Koranic school. Emerging from that experience with a smattering of classical Arabic and the ability to recite the Koran without understanding a word of it, Usman started looking for work.

His internet searches led him to one Abou Obeida, who reminded Usman of the sincere Muslim's obligation to undertake jihad and to live in accordance with Sharia law.

The missing decade?

Muhammed Usman categorically denies Pakistani police information associating him with a local Al Qaida-linked Islamist group and, eventually, with the Taliban in neighbouring Afghanistan.

"No, that's not true!" said the accused.

There does, however, appear to be a 10- or 12-year gap in Usman's curriculum vitae. He says he was studying.

His internet relationship with Abou Obeida eventually led to his departure for Syria, "so that he could live under pure, original Islamic law".

"You mean, where adultery was punished by stoning to death, homosexuals were thrown out of sixth-floor windows, thieves had their hands cut off?" asked the tribunal president.

"Yes, at the time, I believed that. I was young."

Muhammed Usman arrived in Syria sometime in 2015, and was accepted into the ranks of Islamic State. He was immediately sent to Fallujah in Iraq. There, if he is to be believed, he spent weeks reading the Koran and going to the mosque. He denies having taken part in any armed operations.

'Violent action of vengeance'

Transfered to Raaqa, Usman met Oussama Atar, the mastermind of the Paris attacks, and was convinced by him of the need to undertake "a violent action" against France. This was, according to the standard IS propaganda line, to avenge the women and children killed and injured by French planes in coalition air raids.

Usman says he had no idea that he was being asked to go on a suicide mission, nor that the "violent action" was going to kill so many people.

"What would have been an 'acceptable' number of victims for you?" asked the court president, Jean-Louis Périès, exasperated.

"I didn't know it was going to be like that. It was just for revenge," he said in French.

"How was it going to happen if not by suicide attack?" asked the president.

Usman immediately switched to Urdu, meaning that the utterances of this powerful man much given to explanatory gestures with his hands were suddenly relayed in the gentle voice of his female translator. "I have already told you that I did not understand the details. I didn't know if I was being sent on my own or with others. I just knew it was a revenge attack.

"I was stunned when I learned what had happened in Paris."

Muhammed Usman never made it to the French capital. He was arrested with another of the accused, Adel Haddadi, first in Greece, then in Austria. The two Iraqis with whom Usman and Haddadi left Syria reached Paris and died in suicide explosions at the Stade de France.

Asked to explain why he had been chosen to take part in the Paris mission, Usman retreated into the confusion of his native language and offered no clarity.

"Where is the truth?" he was asked at one stage.

"I have already told you the truth, in detail," he answered, speaking Urdu.

The trial continues.

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...