Breathe and the price of petrol goes up. The tomato seller gives you one—just one tomato for One Cedi. But you remind yourself the fact that from time to time, tomatoes and other seasonal goods come back in season and you do not have to with each tomato, lose a Cedi. But even then, these tomatoes in abundance are not as consequential as they used to be. Two cedis is not as powerful as it used to be in the realm of tomatoes, onions, garden eggs, etc. The cost of renting is now casually and notoriously in the thousands—even for single-roomed chamber and hall apartments.

These memes, flying around, they speak the truth, “We no longer see money lying on the ground. We have lost our culture!” True. As direly as you are guarding your one Cedi; I am too, mine. Chances of a stray Cedi are, on a scale of zero to ten, negative one. But like our friend Gatsby of last two weeks, we have an extraordinary gift for hope, so we hope for a return to equilibrium, maybe what we are experiencing is the immediate side effect of a global pandemic. Economies had to be affected by a pandemic as eventful as COVID-19, no? Well, to such a question, a country like America, will respond with ‘cry your own cry.” And we briefly looked at that in the article ‘When You’re Dying You Say We Are Dying’

Back to these tomatoes of ours and our experimentations with hope: after purchasing that tomato, we leave begrudgingly, pressing against them, coyly counting them with our fingers, yet hoping that by our second trip to the vendor, things would have taken shape. But each trip is us nearing this realisation: the cost of living is just… high.

The Science of Blaming

We are going to blame it on the government. And you and I here on ‘Attempted Prophecies,’ not being one to make someone feel left out, we like to be inclusive even in our blaming—so, yes ‘governments’ (past and present). But before we do that, exercise this ‘right to blame’ we citizens are endowed with, let’s look at electricity. And the lights being on, the reflection in the mirror stares back at us glaringly, so we cannot escape the fine lines—the minor details. We cannot escape the part we have to play—or are willing to play.

When I sat down with Dr. Nii Darko Asante for the first in our longline of inquisitions into the nation’s energy sector, there was this question I wanted so badly to ask, but was very hesitant, because you see, I already knew the answer to it, but wanting so badly to protect the little Cedis I had left, I thought it best to leave out.

And then I remembered Jonah…the whole thing about him being swallowed by a whale when trying to escape an assignment—by none other than God. I didn’t know what or whose belly I might end up in if I didn’t comply with your assignment. So as begrudgingly to the tomato seller, I, to Dr. Asante, went: considering how wild the market can be, how high the cost of living is, right from petrol to housing, it becomes to me, as citizen, a great relief knowing that after facing these absurd surges, I will come home, switch on the light, and know that even as the fridge is running, the amount I am paying as electricity bill is, unlike any other commodity on the Ghanaian market, not on the high side. So, in the question of ‘households and industries who pays less,’ I, a citizen, am tempted to go for the former. And in Ghana, that has been the status quo. Am I wrong in so thinking, Dr. Asante?

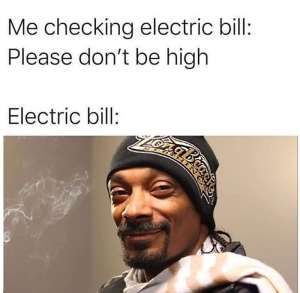

“Price of electricity will have to go up. The only factor that will prevent this would be our governments not having the confidence to do so.” Dr. Asante responded matter-of-factly, his mask hiding his empathy. My heart jumped straight into my mouth. Which is a ridiculous thing because this is a fact you and I (perhaps) already know. It is the John 14:15 of national discussions—known but widely ignored.

Will a reduction of industries’ electricity tariffs have a ripple effect on the economy as a whole? I offered further elaboration to my question to Dr. Asante. Because it would be a shame for the citizenry to find persisting still, a widespread high cost of living, and to come home to face a ‘high cost of staying,’ if you will—electricity costs for households having risen but having not resulted in a decrease in the cost of living as envisaged. Dr. Asante, being himself a citizen, agreed with this sentiment.

“The funds collected for electricity from us all only make up about less than 50 percent of the cost of supplying us with electricity. The tariff rates we are presently running were set about two years ago. And inflation, as we know, has gone up since then. Add to this fact, is the prevailing canker of electricity theft still rampant in the country—many of us are not paying for the power we use.

Ideally both industries and households have to pay more. But truthfully, the factor that would cause a transformation in our economy will be for our homes to bear more of the cost than industry. It is a difficult thing to do, but a very necessary thing to do.” Let’s take this step by step.

“Give, and it will be given to you…” Luke 6:38.

Now, being a somewhat failed prophet (having been unsuccessful establishing a mega church) I have a fair grasp on the politics of giving so as to receive.

Electricity tariffs in a country are predicated on a number of factors, with the cost of power generation, cost of transmission and distribution being key determinants. And with institutions set up for its administration being in certain national circumstances ‘non-profit,’ the ultimate aim becomes the provision of electricity itself, and the pay-off becomes ‘not running at a loss.’ If the government won’t make profit providing the populace with this much needed commodity, electricity, it mustn’t also render itself indebted in doing so. Otherwise, what that becomes of this supposed governmental good intentions is quite plainly, bad governance. So, with subsidies, the government makes the cost of electricity cheaper for the populace. In the exercising of good governance, governments in determining tariffs set differing prices for differing customer-bases—residential, commercial, and industrial.

In a developing country like ours, should electricity pricing be left solely in the hands of demand and supply, the poor would be trumped out of this basic national need, and it becomes in the nation, electricity as luxury. Governments intercede heavily with regulated prices. And in regulating prices, a large chunk of governments worldwide find the most utility charging residential consumers more than industrial consumers.

But with the burden of regulation of prices placed on the government, quite easily, the least misstep may lead to the accumulation of debts in this sector. And with time, an overall deterioration of that segment of the economy—as dire as it is to national growth—results. And in many instances, this good intended by the government, turns (negligently or sometimes intentionally) bad. “Electricity tariffs suffer heavy distortions in many developing countries because of undue government influence,” Isaac Iwuagwu, very cognizant of the equitable reasons behind these governmental interventions in prices, wrote in 2001. “…electricity tariffs must be adjusted to acceptable economic levels…” He continued, proving that it wasn’t the government’s regulation per se that was deemed undesirable, but the fact that its intended target are not met.

“Worldwide, there are very few countries where industries pay more than homes when it comes to electricity.” I am paraphrasing the Senior Minister, Yaw Osafo-Maafo. “Industry subsiding residential power must stop,’ was the CEO of AGI, Seth Twum Akwaboah’s outcry right here in an interview with B&FT somewhere in July. “Industry does not vote, I always say,” said Dr. Asante, having, on his own, reiterated these same sentiments on numerous occasions. “What we have on our hands is a tariff system which quite plainly is biased against businesses and industries. In every part of the world, industry gets electricity cheaper.” He continued.

In the USA, for instance, as of 2020, the annual average retail price of electricity was around 13.15 cents per kWh for residential, and as low as 6.67 cents per kWh for industries. In UK, electricity price, during first quarter of 2021 stood at 20 pence per kWh for households, and 17 pence per KWh for industries. In Germany, a country with one of the highest electricity tariffs worldwide, tariffs for household stood at around 36 cents per kWh, with that of industry being around 24 cents. In China, a nation having one of the lowest electricity prices, tariffs stood at around 9 cents for households and a mere 1 cent per kWh for industries. In South Africa households paid around 14 cents with industries paying half that price, around 7 cents. In Kenya, households paid around 22 cents while industries paid 17 cents. Worldwide, a large chunk of countries gravitate more towards burdening households more than they do industries. On average, worldwide, households paid 27 cents as against industries’ 23 cents per kWh for electricity during that same period. Very few countries find themselves outside this norm—this crucial economic move. Amidst those few countries we have our very own nation, Ghana charging homes 6 cents per kWh, while industries pay more than double the tariffs of households—13 cents per kWh. Ghana’s buddy-buddy, Nigeria finds itself in this band of ‘outlaws.’ Nigeria, just like Ghana, had households paying 6 cents, but with industries paying 9 cents.

This is ironic, don’t you think?—the fact that Ghana, the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to attain independence, and after attaining this heavily sought liberation, sought right after to chase electricity because in the words of Nkrumah, “It was obvious that the project would have to wait for independence…As soon as we became free, I started pushing the project [Akosombo Dam]…” should find itself amidst this tiny group of ‘outlaws.’ “One of my greatest dreams was coming true, in a few years, there will be sufficient power to serve the needs of our industrial growth for a long time ahead. But the dream was killed.” The murder Nkrumah purports in this case was the 1966 coup. But that’s not the matter at hand. The matter might just be that Nkrumah, should he be around to witness industries, the principal segment of the nation for which electricity was tediously sought, be burdened with such high tariffs, that right there would be where he would peg the actual ‘killing’ of his dream.

A Virtuous Opportunity Missed

“Today, electricity is not chiefly intended to drive industry, but to fuel homes. Prioritising household over industries reaps adverse effects on the country as a whole. High cost of electricity tariffs contribute to the high cost of production that industries in the country face. Industries in this country are struggling. And to allay this struggle, they resort to employing very scant workforces, overworking yet underpaying them. Prices of items, even though manufactured in our own country, become inescapably high. The public is faced with a market flooded with imported goods, cheaper than goods manufactured in their own country. Businesses do not expand, they remain same at best, and in most cases, retrogress.” Dr. Asante lamented.

The consumer, being us, and we, being each perhaps products of these same industries and businesses burdened with these high electricity tariffs, end up having little in our pockets to spend, having been paid little by these industries. In the end, the Ghanaian is rendered too broke to be patriotic. The “Buy Ghana” rhetoric become, to us, just two words that sound good together—beautifully paired, yet meaning little to nothing. This may just be one of the few times Luke 6:38 is done justice—because in holding on to our cheaper electricity bills while industry bear our load, industry meets us on the market, on our pay slips, follows us everywhere we go with its drowning fiscal repercussions.

We could have chosen to remain so in this cycle, as vicious as it may be, and as I said, mollify ourselves with the fact that after facing such a tough market, we can be assured that upon going back home, to our sanctuaries, when we put on the light, the fan or air conditioner, the TV, our fridge having stayed on the entirety of the day, home will be much gentler to our pockets.

But with AfCFTA, and especially with Madam Ghana allowing itself to house its Secretariat, we cannot afford to keep industry strangled. Because with this free trade area, in as much as we have integration ensuing, we all in the continent cannot deny that a track has been drawn, a race kickstarted—countries will per their own doing either come out as winners or losers in this vast space of trade. And Ghana, again, home to AfCFTA would be, it cannot be denied, quite the clown of a host should we find ourselves in the losing team, with our industries ill-equipped to take on the challenge and opportunity of a wide market.

Tragedy of Power

And hydroelectric power, being indispensable to industry, and in Nkrumah’s own words, “All industries of any major economic significance require, as a basic facility, a large and reliable source of power. Newer nations, like our own, which are determined to catch up, must have a plentiful supply of electricity if they are to achieve any large-scale industrial advance. This, basically, was the justification for the Volta River Project…” one cannot deny the fact that what we have ensuing is probably perhaps best termed a ‘tragedy of power’—power has been achieved, but its principal object has been woefully kept on the backburner. Sustained industrialisation, one resulting in the driving of economic growth, has been a long time coming in this country. That is not a good thing.

Perhaps in the developed world, having largely orchestrated the Industrial Revolution (from the very First all the way to this Fourth Revolution), their individual citizenries-turned-industries being the originator of, among others, the invention of electricity itself, could not realistically be dealt a bad hand. They couldn’t realistically be made to pay more for something they themselves invented. Maybe, in countries such as ours, not being in the originating positions of global advancement, and in this case industrialisation, we are more likely to miss the point, and commit such atrocious mistakes. Mistakes that result in us missing out on certain propitious virtuous cycle, one that positively affect the economy on all fronts, from increasing manufacturing, to causing reduction in prices of goods and services, creating jobs, to encouraging entrepreneurships.

And the highly productive private sector, now having sprang up all over the country in large numbers and across diverse sectors, will cause an increase in the demand of labour force. And the government itself in need of labour force to drive its institutions and agencies will have to render itself competitive, since people will have on their hands more private sector vacancies than they can choose from, and in the next speech by a minister of state, the narrative wouldn’t be ‘government payroll is full,’ but rather, ‘please come to us, we have vacancies’. And we—we the citizenry, highly in demand, will say something along the line of ‘no!’ But oh! we dream…

You are right in being pessimistic just now. Because we seem to be digging near the ‘all eggs in one basket’ grave again—the ‘one saviour’ trap once again, putting all our eggs in a reduction in electricity tariffs basket. We are not saying this is the solution to all our problems. But if we do this right, and in a mix of doing right other development imperatives, the effect of this one change can be enormous.

I know that’s a lot of philosophical yammering for performing a task as mundane as buying tomatoes. But these were exactly my thought on the drive back home, after having bought that ingredient. Because my anger at the tomato seller reminded me that I had an article to write. So angry that I didn’t see that pothole approaching. These damn roads!

BY YAO AFRA YAO

'Ghana beyond aid' has turned out to be 'Ghana without compass' – Naana Opoku-Ag...

'Ghana beyond aid' has turned out to be 'Ghana without compass' – Naana Opoku-Ag...

Nation builder Mahama will deliver on his promise of a 24-hour economy for the b...

Nation builder Mahama will deliver on his promise of a 24-hour economy for the b...

Prof Jane Naana is more than qualified to be Ghana’s first vice president and ev...

Prof Jane Naana is more than qualified to be Ghana’s first vice president and ev...

WENDA petitions Akufo-Addo, Speaker of Parliament to make vote-buying illegal

WENDA petitions Akufo-Addo, Speaker of Parliament to make vote-buying illegal

Supreme court declares payment of wages to spouses of President, Vice President ...

Supreme court declares payment of wages to spouses of President, Vice President ...

Publish full KPMG report on SML-GRA contract – Bright Simons to Akufo-Addo

Publish full KPMG report on SML-GRA contract – Bright Simons to Akufo-Addo

Kumasi International Airport to begin full operations by end of June

Kumasi International Airport to begin full operations by end of June

Election 2024: Our ‘real challenge’ is getting ‘un-bothered’ youth to vote – Abu...

Election 2024: Our ‘real challenge’ is getting ‘un-bothered’ youth to vote – Abu...

[Full text] Findings and recommendations by KPMG on SML-GRA contract

[Full text] Findings and recommendations by KPMG on SML-GRA contract

Renegotiate SML contract – Akufo-Addo to GRA, Finance Ministry

Renegotiate SML contract – Akufo-Addo to GRA, Finance Ministry