[A continuation from last week’s ‘Not for The Rich Folks (1)’ where the writer yapped—for the umpteenth time—about the need for University/Industry Collaborations to spur national and continental growth.]

Find the money

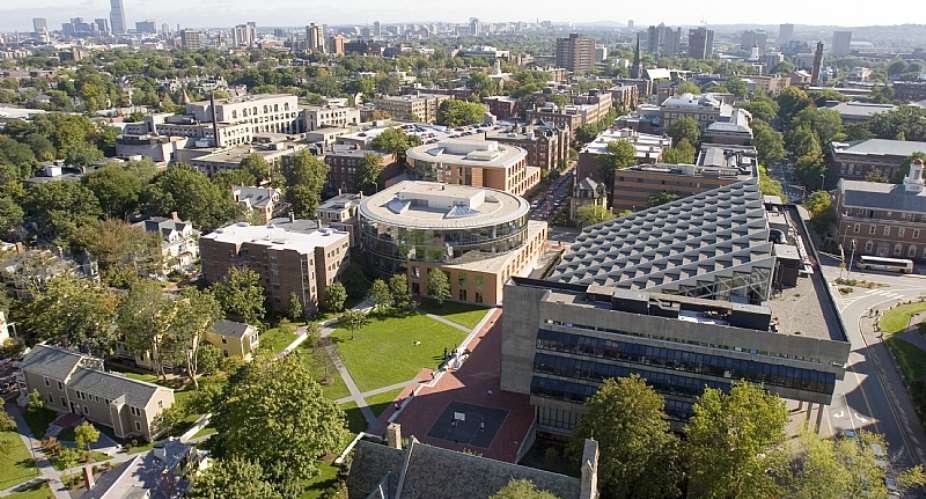

You see, one needs money to make money, and we do not have the money—that, in a nutshell, is our excuse for not following suit in building on this propitious higher learning/industrialisation nexus whose success rate at helping develop countries can never risk an over-exaggeration. To be fair, this excuse, this exaggeration of figures—acting as a disincentive to research universities—is not peculiar to African countries. One’s mind is immediately drawn to the sum of US$50 million (about US$5 billion today) with its accompanying period of 200 years quoted by the former Harvard University president to John Rockefeller in the 19th century as the total amount and time needed to create one— just one research university in USA. Yet in 1890, Rockefeller had to donate only the sum of US$600,000 (over US$25 million today); and along with other private contributions, a much lesser cumulative sum was all the University of Chicago required to achieve its mission of attaining world-class status—taking the university just 20 years to realise this. It took Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), and Nanyang Technological University (Singapore), both founded in 1991, only a decade to join the ranks of the best universities in the world—earning them the reputation as two of the fastest growing universities worldwide—all this done with a considerably lesser amount than quoted by this former Harvard president.

In this 21st century global knowledge age, this paradigm-shifting ability of research universities to serve as a link between countries, global science and technology is even more telling. They, as indicated, have that prerequisite flexibility to adapt to this ever-changing world of ideas and innovation—and a country like United States of America realises this. The country has about 160 research universities, out of its 5,300 tertiary institutions. This, although it may come off as proportionally skewed, is by no means a small number of research universities. These universities, while they typically appoint professors well-steeped in the conducting of research, also duly incentivise these professors. The enormity of the mandate placed on research universities requires funding—constant and ample funding. Yet, the world’s wealthiest economy, knowing very well, having tried and tested, having found true the importance of research universities has, since the onset of the Great Recession, radically reduced its support to these institutions. The United States of America continues to reduce its funding to its research universities. The response of these universities has been singular.

Enter: Public/ Private Partnerships

When public funding proved insufficient, the private sector lent its hand; universities of the developed world sought to make this happen. In 1861, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was founded, purposed to help drive the increasing industrialisation USA was experiencing. The institution, greatly influenced by the German research university model, was very much plagued by financial burdens from its inception. Since its inception, the institution has depended heavily on private sponsors, some of whom, in its early days, have included George Eastman, founder of The Eastman Kodak Company; and in modern times, Bill Gates. The institution, now easily one of the most innovative institutions of higher learning, and having numerous innovations and patents under its belt—as many as 93 Nobel laureates, about 60 National Medal of Science recipients, over 40 astronauts, etc., had a very familiar humble and checkered beginning of insufficiency.

In 1919, the university, short of funding, created a division aimed at imploring private entities to finance academic research. This initiative blossomed into full-fledged series of partnerships with various corporation some few years later. The university experienced a great surge in its scientific knowledge production and innovations as a result. This success story, however, is not indicative of the infallibility of university-industry partnerships, for, in this case, a stock market crash experienced by the country resulted in a plunge in the budget of this university; private investors began pulling out funding. When the private sector proved incapable of continuing its support for research universities, the government stepped back in. Franklin Roosevelt, then President, invented a new model which saw to the provision of funds for research institutions. What resulted from this model includes, inter alia, an advancement in the knowledge of the disease malaria.

Funding for American research institutions has been volatile—is all the writer is saying; and this is the world’s largest economy!

Today, the pool from which American universities draw their funds is large: state funding, tuition, philanthropy, gifts and grants from non-profit foundations and private organisations, fundraising from alumni, revenue derived from partnerships with private institutions, et al.

Germany has nearly 400 state-approved institutions of higher learning. About 110 are universities (imparting theoretical knowledge) and technical universities; and 220, universities of applied sciences. These universities per the German Constitution (Basic Law), are the responsibilities of the individual federal states (Länder)—exercise of which they undertake autonomously. This autonomy comes with it, the responsibility of funding. However, even the German system, though no novice, is not perfect. These states do not play superman—they still require a helping hand. Thus, German research universities, quite like their American counterparts, also derive funds from, governmental bodies (federal government and state government); various organisations: e.g. German Research Foundation (DFG) and German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), non-research institutions, private industry, other public and private bodies, the European Union, and charitable organisations, etc.

Science, from time since, has been ambitious, often to its own dismay, but hindered by a constant lack of means of realisation—funding. That should never be a deterrent to a country to partake in the yielding of its fruits. The application of science as engine for development, and the utilisation of universities to spur the development agenda should be seen as a basic need of developing nations, a crucial means to attaining an end—development, not a privilege of development. One realises that this narrative of the developed world—the citing of countries such as Germany and USA as examples—is not intended to present to the African, flawless systems for the drooling over, but rather it is to serve as a lesson in persistence. This Achilles’ heel—this issue of funding is an infirmity all suffer—rich and poor nations alike. What sets the former apart is their ability to realise the indispensability of certain economic imperatives—research universities, being one of such indispensables. African countries, failing to realise this, continue to place last in all rankings in science and technology, and higher education. In this globalised knowledge production and information age, the impact of African countries are almost non-existent. The continent, on average, generates less than 1% of the world’s research which is not shocking considering the fact that the continent contributes less than 1% of the global expenditure on research and development. African countries comprise eight out of the ten bottom nations ranked by innovation prowess, according to the Global Innovation Index (GII). These numbers and others cited on the continent throughout this article are, without doubt, abysmal.

Research institutions play a vital role in development, thus developed countries are right in rummaging through all sources to fund them. Developing countries ought to follow suit. Governments of African countries cannot be expected to alone shoulder this burden, however; this makes public/private partnerships a vital tool for development.

The impact of science and technology on the modern world suffer redundancy upon reiteration. The impact of universities on science and technology, ergo development, however thirsts for reiteration. The good research universities serve is vast. The biotech industry of USA, for instance, is almost entirely attributed to the nation’s research universities. Research universities have their marks on numerous start-ups and patents in many industries in developed countries.

The world owes a lot to researches that have sprung out of these universities—be they basic or applied research. The inventions of smartphones, malaria treatments, agricultural advancements, Google, ATMs, the internet, antibiotics, computers—the list is long!—all trace their origins to research universities. Research universities create a culture of innovations that—in its graduates, citizenry of the country, and on the world as a whole—encourage entrepreneurships. Universities stand a better chance of selflessly managing their intellectual property for societal good, since most of them, worldwide, are public institutions.

The realisation of the enormous benefits of research universities, and the placement of all efforts in creating them, creates a virtuous cycle of public/private partnerships helping spur technological advancements and innovations, sustainable industrialisation, etc. resulting in increased productivity, decreased cost of living, increased standard of living, economic and socio-economic development etc. Instead that which is being witnessed in Africa is a vicious cycle of abject poverty, dependency on raw materials, high unemployment rates, prevalence of diseases, failing healthcare systems, high cost of living, low standard of living, slum-filled cities, etc. This is not shocking for our response to the call to build on the propitious university/industrialisation nexus has virtually been: it is money that breeds money; the accompanying implication being: poverty must breed poverty.

So here we are, a people primarily dependent, in this highly industrialised age, on the export of raw materials; a continent comprising nations which are barely industrialised in a highly globalised age; countries insufficiently equipped to take on the challenges and advantages of growth. The call on African countries to industrialise is—for their own good—now peremptory. The call for the establishment of research universities in African countries is, now for the continent’s own good, too, peremptory. African countries do not have the luxury of 200 years—USA sure did not have that luxury either—to build a research university. Decades spent on this may even be considered a sluggish pace. Why this urgency? Globalisation.

This need for African countries to eliminate their long-standing dependency on the export of raw materials by promoting sustainable industrialisation through the establishment of research universities; create jobs, provide great healthcare systems, et al has always been dire. Why also even more so keen now?

Urbanisation.

[Published in the Business & Financial Time, B&FT - 28th April, 2021]

Dumsor: Mathew Opoku Prempeh has been disrespectful, he should be fired – IES

Dumsor: Mathew Opoku Prempeh has been disrespectful, he should be fired – IES

NPP prioritizing politics over power crisis solution — PR Strategist

NPP prioritizing politics over power crisis solution — PR Strategist

E/R: Gory accidents kills 3 persons at Aseseaso, several others critically injur...

E/R: Gory accidents kills 3 persons at Aseseaso, several others critically injur...

Nobody can come up with 'dumsor' timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Nobody can come up with 'dumsor' timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Dumsor: You ‘the men’ find it difficult to draw timetable when ‘incompetent’ NDC...

Dumsor: You ‘the men’ find it difficult to draw timetable when ‘incompetent’ NDC...

We’re working to restore supply after heavy rains caused outages in parts of Gre...

We’re working to restore supply after heavy rains caused outages in parts of Gre...

NPP government plans to expand rail network to every region — Peter Amewu

NPP government plans to expand rail network to every region — Peter Amewu

Dumsor must stop vigil part 2: We’ll choose how we demonstrate and who to partne...

Dumsor must stop vigil part 2: We’ll choose how we demonstrate and who to partne...

2024 elections: NDC stands on the side of morality, truth; NPP isn't an option —...

2024 elections: NDC stands on the side of morality, truth; NPP isn't an option —...

Akufo-Addo has moved Ghana from 'Beyond Aid' to ‘Beyond Borrowing’ — Haruna Idri...

Akufo-Addo has moved Ghana from 'Beyond Aid' to ‘Beyond Borrowing’ — Haruna Idri...