The brutal murder of African-American man George Floyd at the hands of a police officer sent shock waves around the world. Paris Perspective looks at how the ensuing outrage against discrimination, impunity and racial profiling in the US has been echoed in France.

On 25 May 2020, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was filmed restraining the 46-year-old Floyd, who suffocated after being pinned to the ground by the neck and back more than nine minutes.

Footage of his death saw millions of people around the world take to the streets demanding justice for Floyd, and an end to police brutality against ethnic minorities and the impunity of officers.

Following a high profile trial, Chauvin was this week found guilty of Floyd's murder and faces up to 40 years in prison.

The case of Adama Traoré

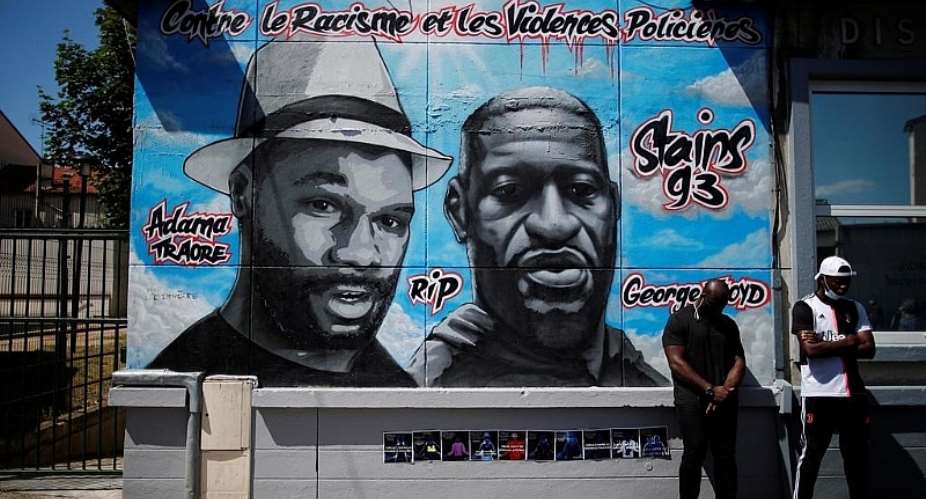

The issue of discrimination in the United States has resonated with minorities in France, with Floyd's death opening old wounds – namely the 2016 death in custody of 24-year-old Adama Traoré, who was also pinned to the floor by police while handcuffed.

An initial report concluded that Traoré died by asphyxiation. This was overturned when it was decided that an underlying heart condition and genetic illness were to blame.

Traoré's family accused police of a cover-up and demanded an independent investigation.

The resulting report from Belgian doctors claimed, somewhat inconclusively, that he died of heatstroke but that suffocation could have been a factor. An “underlying condition”, they said, could not be ruled out.

Excessive force by police officers is racially targeted both in France and the United States, says Curtis Young, a Paris-based historian and professor of literature and contemporary politics.

“This construction of the 'other' is racialising. In America it's the African-American. Right now, it's also the Asian-American," Young tells RFI.

“There has been the construction of an 'other' from the beginning of the American project. It is also part of the colonial project that Europe was engaged in since the 19th century. France colonised all of West Africa.

This narrative, which Young says resonates through daily life in France, is the basis upon which discrimination occurs. "It gives you the licence to do as you will."

Racial profiling in the dock

In 2017, a report from the Rights Defender, an independent French administrative body, found that youths aged between 18 and 25 were seven times more likely to stopped by police for ID checks.

If you were a black adult or of North African descent, the likelihood of being stopped by the police then increased five-fold.

In a multicultural, pluralist and open society like France, it could be argued that such demographic profiling is more about socio-economic discrimination and less about race. Not so, says Young.

“I think the overriding identifier is the colour of the skin," he says. "There are poor kids across the demographic spectrum – but there's an assumption that 'this is a black kid, and probably doing something wrong', while dozens of other kids walk by.”

In January, six NGOs filed a class action lawsuit against the French government over allegations of systemic discrimination within the police force. They cited racial profiling and called for institutional reforms.

Including groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, the NGOs were quick to clarify they were not directly accusing the police force of being racist, but of operating a system that generated discriminatory tactics.

The 'colour blind' paradox

Calling out abstract faults within the system without directly addressing the practices that need to be reformed is essentially doublespeak, says Young.

“We're taught that there's a difference between human beings from a very early age. We're taught there's something different about these people, and we have to keep an eye on them," he says.

“Then we grow up and we become policemen, judges and administrators. We bring that with us. Nobody is innocent. We bring this to the job.”

Young says the notion that we're "looking for something outside of us that needs to be fixed" is distracting from the real need for people to look to themselves for the solution.

France has worked hard to create a “colour-blind” public sphere – in which race is invisible – even striking the word "race" from its constitution. But the notion of colour-blind society is nonsense, says Young.

“How can you be blind to the fact that I'm a person of colour? How can I not see that you are of the ethnicity that you are?

"The question is, what do I do with that? Do I make a judgement about that? And what kind of a judgement do I make about that one person against the other?"

Ideas of colour blindness are avoiding the question, he adds.

The colour-blind paradox brings to the fore the zeitgeist of replacement theorists in the United States: the idea that Black people, immigrants and Hispanics are going to replace the ruling white classes.

In France, this type of rhetoric was employed by the founding father of the far-right National Front, Jean Marie LePen.

False narratives and distraction tactics

A decades-old student union in France spurred outrage recently when it emerged that it had barred while people from attending some of its meetings in order to create spaces to support students of colour.

Socialist candidate in the 2022 French elections, Audrey Pulvar, agreed white people should be barred, while at the same time saying no one should be excluded.

This sort of doublespeak, says Young, is yet another area that needs work.

“We have the politically correct police that are always hovering about, ready to grab onto a piece of an idea in order to take the attention away from what the real problem is,” he says.

False narratives in turn create a state of defensiveness that allows people like the far-right French polemicist Eric Zemmour come forward and say “Aha! You see that's how all of them are”.

From Rodney King to George Floyd, little has changed

Anti-racism protests in France that followed George Floyd's murder are viewed as a moment of reckoning for all the injustices that have been forced on French people of colour.

Adama Traoré, five years after his death, was quickly dubbed the “French George Floyd”.

“Here's how it's connected”, Young explains. “For me, the George Floyd moment was not an equivocal moment. It was clear.

“This was a raw human moment of a man having the life squeezed out of him, gratuitously, by a cop with his sunglasses on the top of his head and one hand in his pocket.”

So what makes Floyd's killing different to that of Rodney King, who was pulled from his truck in 1992 sparking riots in Los Angeles?

“The lens has sharpened. The lens is clear. Rodney King – that was fuzzy – we're not sure if he wasn't doing something wrong,” says Young.

“George Floyd was sitting down; he was not resisting … There are no more excuses.”

In the 28 years that have passed since the LA riots – and in the wake of global disgust at the inequalities highlighted by Floyd's murder – has the US implemented any institutional reforms to keep such impunity in check?

“No” says Young. “But, hopefully this [case] will bring some things out.”

- Row over 'non-whites-only' student meetings as campaigning politicians wade in

- Defining and celebrating blackness in the face of French universalism

Chauvin trial, which saw him convicted on all counts of second-degree murder, third-degree murder and manslaughter, gave rise to some unprecedented events.

Breaking the institutional code of silence, Minneapolis's police chief testified against one of his officers.

"That code of silence has been absolutely broken," says Young. "This opens a door to another conversation about the role of the police and who they are there to protect and serve.”

Written, produced & presented by David Coffey

Recorded, mixed & edited by Vincent Pora

Curtis Young is currently a Professor of Literature at the ESSEC Business School, Cergy.

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...