With a recent book followed by thousands of public testimonies under the #MeTooInceste hashtag, survivors of sexual abuse by family members believe French society may be starting to face up to incest, a taboo topic that a recent estimate says has affected one in 10 people in France.

The first weeks of 2021 have seen an outpouring of public testimonies of sexual abuse at the hands of family members in France.

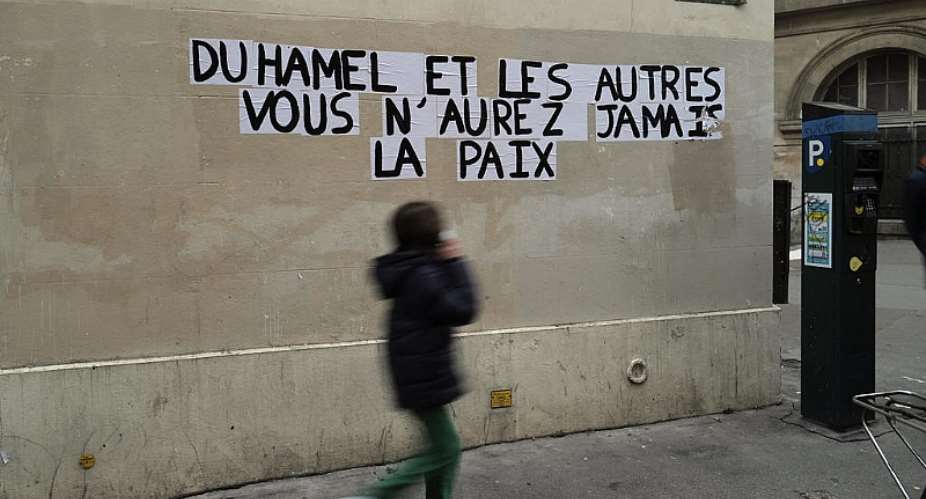

First came the publication on 5 January of La Familia Grande, in which author Camille Kouchner accuses her stepfather, prominent French intellectual Olivier Duhamel, of raping her twin brother when they were teenagers.

Then the weekend of 16-17 January saw thousands of testimonies of incestuous abuse under the social media hashtag #MeTooInceste, following the model of the #MeToo phenomenon of speaking about sexual abuse and harassment.

On Saturday, days after French MPs approved a proposal to toughen punishment for child sexual abuse, insufficient in the eyes of child protection advocates, President Emmanuel Macron asked the government to come up with more proposals.

“This is very significant and quite unexpected,” says Patrick Loiseleur, vice-president of Face à l'inceste (Facing Incest), a survivors' group whose origins stretch back to the year 2000. “For many years, we had the impression of being alone, shouting in the desert. It's like French society is coming out of denial.”

Breaking family cohesion

Survivors' groups have long maintained incest is a widespread phenomenon whose real numbers are largely underestimated.

Based on results of results of a poll the group commissioned by Face à l'incest in November 2020, Ipsos institute estimates one in 10 French people are victims of incest as children or adolescents. The poll found victims to be 78 percent women, 22 percent men.

But those results also suggest growing willingness to speak about incest and identify as a victim: earlier polls showed 3 percent of French people considered themselves victims of incest in 2009 and 6 percent in 2015. Rates of confiding in others and speaking about incest are also on the rise.

Survivors are unsurprised the current phenomenon has taken so long to come, since confronting incest, along with facing barriers inherent in child sexual abuse, also threatens to break family cohesion and to disrupt the sanctity of the private realm as a place of safety from public scrutiny.

“You have to accept losing your family in addition to being the victim of sexual violence,” says Loiseleur, whose group says victims' families only believe allegations of incest in 20 percent of cases.

“In many families, denial is the rule,” Loiseleur continues, adding Kouchner's book illustrates how the dynamic works. “What's really interesting in this book, and specific to incest, is that law of silence, the omerta within families that keeps those crimes well hidden.”

Push to make incest a crime

Legal barriers also exist, where victims, whatever their age at the moment of the incidents, are obliged to enter the legally nebulous terrain of proving non-consent.

“In the definition of rape in French law, the victim is considered consentful by default, until the contrary is proven, even for children, even for incest,” Loiseleur says. “If you are a child, and the perpetrator is your uncle or father, you still have to prove that you were not consentful.”

One of the group's battles has been to have incest recognised as a crime. Since 2016, incest has been included in the penal code as an aggravating circumstance in crimes of rape or sexual violence, but not as a crime in itself.

“We are pushing for reform that makes incest recognised as a crime in itself, apart from rape, because incest is more than rape,” Loiseleur says. “There is something broken in the family relationship, and that must be recognised in the law.”

Can France now take the lead?

Kouchner's book and the #MeTooInceste hashtag represent the kind public awareness that survivors say is needed to overcome legal barriers, and recent weeks have also shown signs of pressure to confront certain attitudes towards incest.

A television network severed ties with a commentator, philosopher Alain Finkielkraut, over comments minimising the allegations against Duhamel on the grounds the victim was 14 years old.

Later, a cartoonist for newspaper Le Monde resigned after the paper's editoral director apologised for publishing a drawing that critics accused of mocking incest victims.

Loiseleur considers there may be a cultural shift in France, which he has has had particularly tolerant attitudes towards child abuse.

“In the 70s and 80s, some people defended the idea that children had the right to sexuality and to freely discover their sexuality, regardless of their age,” he says.

“This is not shared by most of the popultion, who just like me have children and want their children to be safe. But maybe in the French elite, there was a certain reluctance to creating an age of consent.”

Recent years have also seen the legal action against author Gabriel Matzneff, who celebrated his sexual relations with children in books published by leading publishing house Gallimard, and public pressure on filmmaker Roman Polanski, who lives in France to avoid persecution for sexual relations with a child in California.

“I think the movement could go beyond the borders of France,” Loiseleur says. “France was late on this question, but maybe now it will lead.

“In Belgium, there was a proposal to make incest a separate crime. Maybe things will start moving in all of Europe and not only France now.”

This IMANI job no dey pap; the people you are fighting for are always fighting y...

This IMANI job no dey pap; the people you are fighting for are always fighting y...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang has changed; you can see a certain sense of urgency –...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang has changed; you can see a certain sense of urgency –...

MFWA Executive Director slams Akoma FM for engaging in ‘irresponsible’ media pra...

MFWA Executive Director slams Akoma FM for engaging in ‘irresponsible’ media pra...

‘Women must become millionaires too’ — Prof Jane Naana on establishment of Women...

‘Women must become millionaires too’ — Prof Jane Naana on establishment of Women...

Some believe only in Ghanaian votes, not Ghana — Kofi Asare jabs politicians

Some believe only in Ghanaian votes, not Ghana — Kofi Asare jabs politicians

Plan to make BEST sole aggregator of Sentuo Oil Refinery will create market chal...

Plan to make BEST sole aggregator of Sentuo Oil Refinery will create market chal...

2024 elections: I can't have the man I removed from office as my successor — Aku...

2024 elections: I can't have the man I removed from office as my successor — Aku...

2024 Elections: Immediate-past NPP Germany Branch Chairman garners massive votes...

2024 Elections: Immediate-past NPP Germany Branch Chairman garners massive votes...

Gov’t focused on making Ghana energy self-sufficient, eco-friendly – Akufo-Addo

Gov’t focused on making Ghana energy self-sufficient, eco-friendly – Akufo-Addo

April 25: Cedi sells at GHS13.74 to $1, GHS13.14 on BoG interbank

April 25: Cedi sells at GHS13.74 to $1, GHS13.14 on BoG interbank