"Do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do!" an Ethiopian girl sings to her classmates, who are huddled together on a straw mat on the sandy ground of a refugee camp in Sudan.

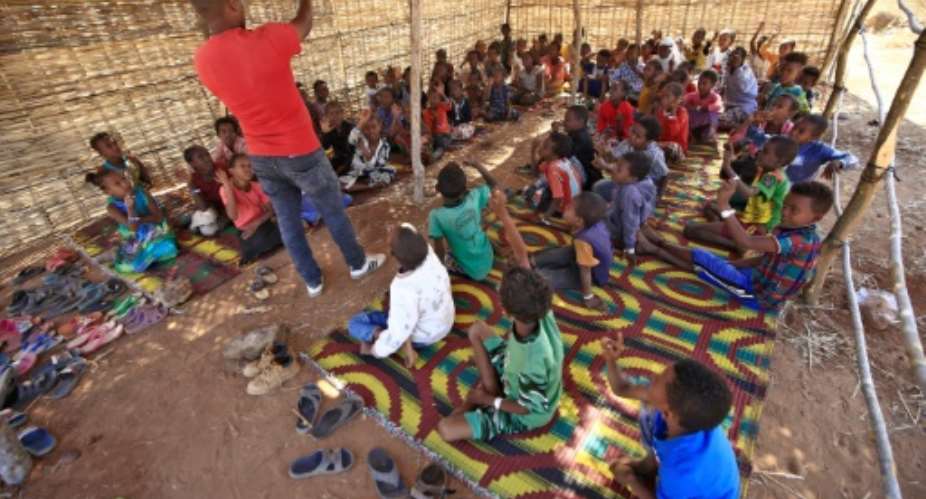

Shielded from the hot mid-afternoon sun in a makeshift classroom built from wood and straw, the children sing the octave back in unison.

When they finish, they laugh as they break out into noisy applause, with nods of approval from their teacher Bereket Weldgebriel.

"Education is the light of the world," Bereket, a 35-year-old English and music teacher, tells AFP.

He and the children in his class are among some 49,000 people who fled their homes after Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's government launched a military operation against the authorities of the northern Tigray region on November 4.

They have found shelter in a string of camps along the Sudanese border, where they live in tents and straw huts.

According to the UN refugee agency, 45 percent of the refugees are children.

"When I came here, my heart was broken," says Bereket, who used to run an English-language academy and teach at a public school in the Tigray town of Humera.

New meaning

Now, he and his colleagues at the temporary Um Raqouba School Site 1 have found meaning to their new lives.

The refugee children are taught in two shifts in five makeshift classrooms made from straw and wood. By ASHRAF SHAZLY (AFP)

The refugee children are taught in two shifts in five makeshift classrooms made from straw and wood. By ASHRAF SHAZLY (AFP)

"If we teach these children, they will be happy," says Bereket, a graduate of the Academy of Music of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa.

"If children have an education, they can solve their problems," says the teacher, who wears his thick black hair in short dreadlocks.

Holding back tears, Bereket says that during the army assault on Humera in early November, he saw "many dead bodies" on the streets.

"I never expected I would see anything like that," he says, pulling his phone out of his pocket to scroll through the photos of his school back home.

No politics

Bereket's boss Teklebrham Giday, 32, was also a schoolteacher in Humera. At Um Raqouba School Site 1, he is the head teacher.

He explains that there are several other makeshift schools in the camps, and that his school has registered 722 students so far, from grades one through 10.

The United Nations says children make up 45 percent of the 49,000 Ethiopians who have sought refuge in neighbouring Sudan. By ASHRAF SHAZLY (AFP)

The United Nations says children make up 45 percent of the 49,000 Ethiopians who have sought refuge in neighbouring Sudan. By ASHRAF SHAZLY (AFP)

Holding a blue folder, a pen and several sheets of paper, Teklebrham says classes are held in morning and afternoon shifts.

With five makeshift classrooms to shield the children from the elements, he and his team offer a basic education to the eager students according to their grade.

With support from the Norwegian Refugee Council, each classroom is equipped with a blackboard and chalk, and the children have notebooks and pens.

"We teach basic subjects: English, our national language Amharic, basic sciences and, for recreation, ... sports, music and arts," says the head teacher, adding that the children also study the language of Tigray, Tigrinya.

"We simply omitted all the subjects dealing with politics," he says. "Many people were killed in Tigray due to politics."

Hope and safety

Teklebrham says he fled Humera after a military officer kicked and beat him with his gun.

Ethiopian refugees arrive at Sudan's Um Raquba camp with few if any belongings but many say schooling for their children is their top priority. By Yasuyoshi CHIBA (AFP)

Ethiopian refugees arrive at Sudan's Um Raquba camp with few if any belongings but many say schooling for their children is their top priority. By Yasuyoshi CHIBA (AFP)

What followed, he says, was an extraordinary exchange with the officer.

Speaking in English, he describes the scene: "I told him: 'My government gave me a chalk to take my responsibility to accomplish my mission to teach children. And ... our government gave you a weapon, so you are (tougher) than me, so you can kill me.' After I talked like that he calmed down and released me."

Now in Um Raqouba, he gathers the teachers for an afternoon meeting, preparing for the next day's classes.

According to Catherine Mercy, education adviser for the NRC, many parents arriving at the camp identified the need for schooling as a key priority, even though most had fled to Sudan with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

"Education provides hope, education provides a routine for the children, education provides a safe space for the children in such times of conflict, education gives a chance for children to hope for a better future," Mercy says.

'Nobody will kill you'

Among the children attending classes at the temporary school is Emmanuel Thagakiros, a 10-year-old boy who wears a green T-shirt and shorts.

The camp's teachers say they want their makeshift classrooms to provide a place where refugee children can feel safe after the horrors some of them saw back home in Ethiopia. By ASHRAF SHAZLY (AFP)

The camp's teachers say they want their makeshift classrooms to provide a place where refugee children can feel safe after the horrors some of them saw back home in Ethiopia. By ASHRAF SHAZLY (AFP)

He says his favourite subject is maths. "I want to learn so I can be happy and get a job to help my parents," he adds shyly.

His 36-year-old mother, Askwal Hagos, says Emmanuel has had frequent nightmares since they fled their home three weeks ago.

Wearing a long white cotton scarf over her hair, she tells AFP through a translator that both she and her son saw "the bodies of people who had been slaughtered" in Humera.

"Even now, he panics. At night, he panics when he dreams about the dead bodies he saw," says Askwal, who has two other children.

When her son is getting ready to go to school in the morning, she tells him: "Here nobody will kill you. Nobody will hurt you."

It’s an abuse of power to arrest ECG officials for performing legitimate duties ...

It’s an abuse of power to arrest ECG officials for performing legitimate duties ...

Unreasonable Actions of GTEC to Collapse Private Universities, Colleges, Institu...

Unreasonable Actions of GTEC to Collapse Private Universities, Colleges, Institu...

Corruption makes a lot of people rich, happy; NDC, NPP cannot help us – Okyeame ...

Corruption makes a lot of people rich, happy; NDC, NPP cannot help us – Okyeame ...

GOIL increases fuel prices again, diesel sells GHC14.80, GHC14.99 per litre of p...

GOIL increases fuel prices again, diesel sells GHC14.80, GHC14.99 per litre of p...

Bawumia will use Ghana’s gold to stabilize the Cedi if voted as President — Ahia...

Bawumia will use Ghana’s gold to stabilize the Cedi if voted as President — Ahia...

Arrival of state-of-the-art bullet trains signify Ghana’s journey towards enhanc...

Arrival of state-of-the-art bullet trains signify Ghana’s journey towards enhanc...

Idea behind Performance Tracker is great but shouldn't be limited to election ye...

Idea behind Performance Tracker is great but shouldn't be limited to election ye...

Election 2024: Bawumia losing 21.8% of NPP’s 2020 Akan votes — Global InfoAnalyt...

Election 2024: Bawumia losing 21.8% of NPP’s 2020 Akan votes — Global InfoAnalyt...

People are celebrating their 80th birthday and Ghana owes GHS650 billion; who is...

People are celebrating their 80th birthday and Ghana owes GHS650 billion; who is...

Court issues arrest warrant for Chinese Iron woman, one other over cantonments l...

Court issues arrest warrant for Chinese Iron woman, one other over cantonments l...