On May 16, 1979, I was in Copenhagen, Denmark, visiting Scandinavia when I went into a news-stand and bought a copy of the New York Herald Tribune – one of the few English-language newspapers that regularly carried news about Africa and which I therefore never failed to peruse when I was abroad.

On an inside page of the paper, I saw a one-paragraph story reporting that “an Air Force officer” had been arrested in Ghana for attempting to overthrow the military government of General F W K Akuffo.

I was extremely disturbed, for I was a member of a Constituent Assembly that had spent months writing a new constitution, under which Ghana was to be returned to civilian rule. What was going on in Ghana? I wondered.

So off to the Ghana Embassy in Copenhagen I went. Fortunately, I knew the Ambassador there – Mr Frank Boateng, who, at an earlier time, had been Secretary to an organisation – one of the many formed by the Nkrumah Government and some of its allies – whose name WAS “World Without The Bomb”. Whenever I had met Frank in those days, I had – in sheer mischief – changed his organisation's name to “Bomb Without The World!” Frank had a good sense of humour, and so he used to laugh and say, “You’re a bad boy!”

So I had no hesitation in approaching him for information. Unfortunately, he had very little knowledge of what was happening in Accra.

The rest of my trip to Scandinavia was, thus, not as enjoyable as the first part, I must confess. My mind was preoccupied with entertaining political scenarios of all sorts: a military officer had once told me that any attempt by a section of the military to overthrow a government that itself is a military government, constituted, by definition, “a civil war”. Was Ghana to embark on a “civil war” only nine years after a very bloody civil war had nearly destroyed neighbouring Nigeria?

I passed through London on my return journey. There, I got to know a bit more about what was happening back home. I learnt that the officer who had led the “attempted coup” was Flight-Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings, a young officer whom I knew!

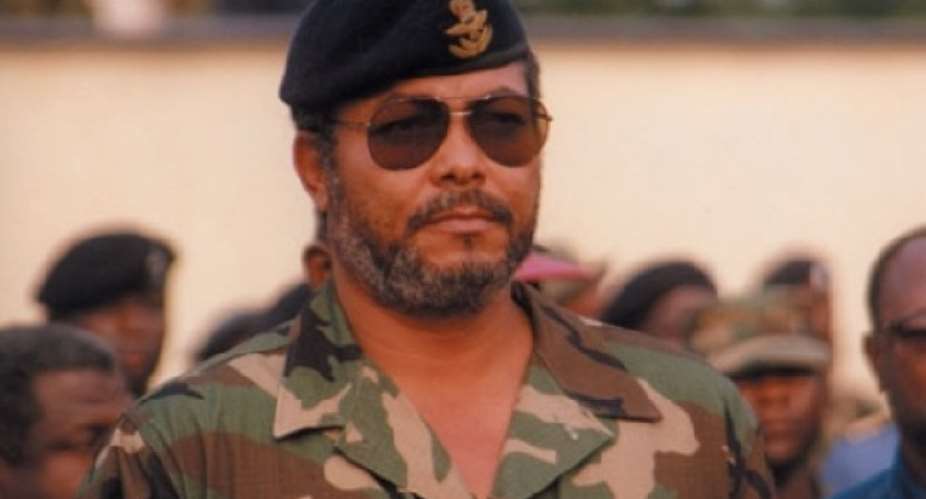

I knew Rawlings because, one day, while visiting my bosom friend, Squadron Leader Ben Owusu, at the Air Force Officers’ Mess, I noticed a light-skinned officer in a very smart uniform. His manner and bearing were striking, in the self-confidence and panache they conveyed. I was impressed enough to ask Ben what the officer’s name was. Ben told me he was called Rawlings.

Not too long after this, whilst I was having a beer with Ben at the Mess, Rawlings approached me and said, out of the blue, with a charming smile: “Sir, we have elected you to be our tutor in current affairs!”

I was taken aback. A lot of officers often bought me a drink and chatted to me about African countries, such as Angola, South Africa, Guinea Bissau, Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

For they needed to know about the guerrilla wars that were going on in these African countries, as those wars featured frequently in the promotion examinations of Ghana’s military officers who wanted to be promoted to the next rank. Now, I had made a special study of these guerrilla movements and talked frequently about them in radio news commentaries. Indeed, I knew many of their leaders personally, having interviewed, on Ghana Television, such figures as the charismatic Samora Machel of Mozambique, the intellectually-deep Amilcar Cabral of Guinea Bissau, and the Zimbabwe leader, Robert Mugabe.

One of my closest friends in the Air Force, Captain “Ben Kidd”, had become a figure of fun because in one examination, he had not been able to write too much about “General Spinoza” (leader of the Portuguese army in Guinea Bissau) and his mocking colleagues had nicknamed him “Spinoza”!

I agreed to the proposal by Rawlings with alacrity, for I enjoyed rapping about what was happening in the African countries suffering from racist oppression. Unfortunately, I never heard from Rawlings again, although I was often accosted in the Mess by other officers and quizzed about what was going on in Africa.

And now, I was learning, in London, that Rawlings is on trial in Accra. What would be his fate? And how would his fate affect the future of the Ghana Air Force? I was keenly interested in the future of the Air Force, because I had many friends in it – especially in the Fourth Squadron (jet fighters), to which Rawlings belonged, and where my friend, Ben Owusu, was also employed, as mentioned earlier.

I returned to Ghana on June 3, 1979. I got home late at night, and so wasn’t able to talk to any of my friends. My plan was to do all my digging for information the next day. But fate was lurking in the shadows, laughing at me. For at about 4:30 am, the roof of my residence at North Labone Estate in Accra – which lay directly in the flight path of aircraft that took off from Accra international airport – was shaken by the loud sound of an Aermacchi jet fighter flying overheard.

My mind reacted quickly: “Something IS happening” (I surmised). “A member of the Jet Squad is on trial. And a jet fighter is flying at such an unusually early hour? The jets would, as a matter of course, have been grounded during the trial, as a security precaution, wouldn’t they? No – something IS happening!”

I didn’t go back to bed. Instead, I tuned my radio to Radio Ghana and waited.

By Cameron Duodu

Meta releases new version of conversational AI across its platforms

Meta releases new version of conversational AI across its platforms

Cape Town named Africa’s Best Airport 2024 by Skytrax

Cape Town named Africa’s Best Airport 2024 by Skytrax

Bono East: Four injured after hearse transporting corpse crashes into a truck

Bono East: Four injured after hearse transporting corpse crashes into a truck

‘Be courageous, find your voice to defend our democracy’ — Sam Jonah urges journ...

‘Be courageous, find your voice to defend our democracy’ — Sam Jonah urges journ...

Exodus of doctors, nurses and teachers have worsened because of unserious Akufo-...

Exodus of doctors, nurses and teachers have worsened because of unserious Akufo-...

2024 election: Avoid insults, cutting down people in search of power – National ...

2024 election: Avoid insults, cutting down people in search of power – National ...

‘You passed through the back door but congratulations’ — Atubiga on Prof Jane Na...

‘You passed through the back door but congratulations’ — Atubiga on Prof Jane Na...

Government’s $21.1 billion added to the stock of public debt has been spent judi...

Government’s $21.1 billion added to the stock of public debt has been spent judi...

Akufo-Addo will soon relocate Mahama’s Ridge Hospital to Kumasi for recommission...

Akufo-Addo will soon relocate Mahama’s Ridge Hospital to Kumasi for recommission...

We must not compromise on our defence of national interest; this is the time to ...

We must not compromise on our defence of national interest; this is the time to ...