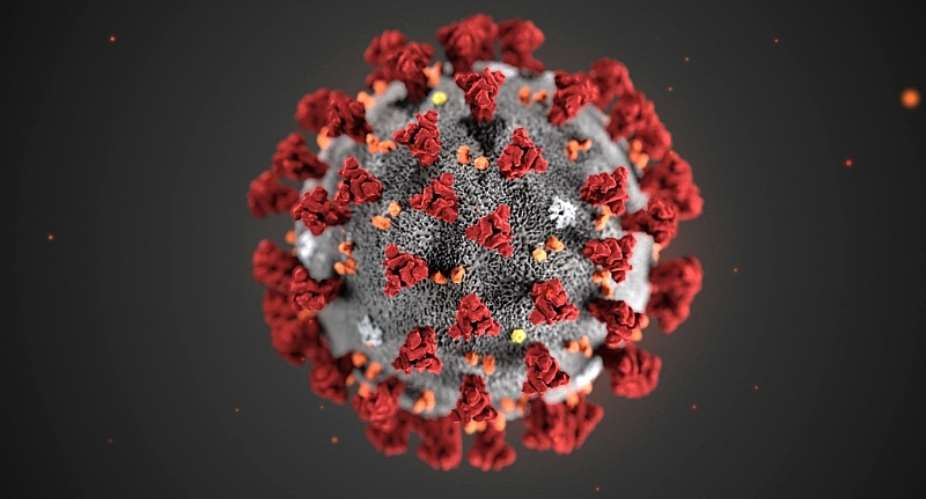

Globally, coronavirus infections have surpassed 5.2 million cases, with 335,002 deaths. However, there has been a remarkable 2,094,919 recoveries. As a pandemic, infections are being confirmed in 215 countries and territories around the world. Currently, no matter how optimistic the situation appears, the daily case updates depict an increasing number of global infections as well as deaths.

Yet, the recoveries leave us with a flickering hope! Sooner as the COVID-19 spread across the world, from China, sooner did countries take initiatives to prevent the spread of the virus. These measures taken by countries to stop rapid spreading of the coronavirus have proven to be burdensome to governments and citizens everywhere. Regrettable but real is the fact that until the scientists discover fit-for-purpose vaccines and precise treatments, physical distancing is reasonably the only intervention available to break the sequence of transmission and save the rest of the uninfected population.

COVID-19 in Ghana

On March 12, 2020, the Minister of Health, Hon. Kwaku Agyemang-Manu announced Ghana's first two cases at an emergency press briefing. It was reported that the two cases were people who came back to the country from Norway and Turkey. The Contact tracing process began with the first cases. From March 12 to May 22, 2020, the initial two cases increased exponentially to 6,486 total confirmed cases, with 31 deaths and 1,951 recoveries.

Global Response and the Consequences

The national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have been wide-ranging, and have included containment measures such as quarantines, curfews and shutdowns or lockdowns. A report by Business Insider (www.businessinsider.com) shows that in April, a third of the world population was on some form of a coronavirus lockdown; meaning their movement was being keenly restricted and controlled by their respective governments. These restrictions (stay-at-home orders and others) taken to prevent further spread of COVID-19, unfortunately, have far-reaching consequences for the global economy. Professors of Economics at London Business School, Paolo Surico and Andrea Galeotti, have demonstrated through their analysis of the “economics of a pandemic: the case of Covid-19” that the impact of the pandemic are already felt on stock markets, travel services, restaurants, supply chain, durables expenditure (cars), oil and gas, etc.

Ghana and the Burden of COVID-19

As governments across the world took initiatives in response to the pandemic, so did the government of Ghana. On March 15, 2020 at 10 pm, President Nana Akufo-Addo, in his first address to the nation on COVID-19, banned all public gatherings including workshops, conferences, funerals, festivals, church or mosque activities, political rallies, and other related events to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Basic schools, senior high schools and universities, both public and private, have also been closed.

With a total of 137 Coronavirus cases as at March 27, 2020 and with evidence of horizontal transmission, the President further declared a two-week partial lockdown to place restrictions on movement in key cities of Greater Accra Region and Kasoa, as well as Kumasi and its environs. This partial lockdown was extended for another one-week and was finally lifted on April 20, 2020. The earlier restrictions on mass gatherings remained in force; and were subsequently extended to May 31, 2020.

The inherent adverse consequences of the restrictive measures prompted the government to lift the partial lockdown, which had proven to be draining the economic life of the nation, notwithstanding the inherent merit of curtailing further community spread of the coronavirus.

The enervating impact COVID-19 pandemic has already been felt on the socio-economic, political, and traditional lives of all Ghanaians. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has described most low- and middle-income countries, as having the majority of their population depending on the informal economy, with scarce resources, persistent gender inequalities, and discrimination. In addition, these countries have the inadequate capacity of some institutional structures – including the health and social protection systems. This limits the room for replication of measures as applied elsewhere. Some additional measures of scale for the informal economy are therefore necessary.

Ghana has over 70 percent of its labour force in the informal sector. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS)describes, the informal sector as made up of businesses – across all sectors – which are not registered with the Registrar-General’s Department (RGD) and do not keep formal accounts. For many Ghanaians in the informal economy, to stop working or working remotely at home is not an option.

In the absence of income replacement or savings, staying home means losing their jobs and, for many, losing their livelihoods. Poor households with savings, in the face of negative income shocks, may have a high marginal propensity to consume. This type of crisis is also characterized by inflation of prices of foodstuffs and other essential commodities.

The GSS has reported that the national year-on-year inflation rate was 10.6% in April 2020, which is 2.8 percentage points higher than March rate. Month-on-month inflation between March 2020 and April 2020 was 3.2%. These are highest recorded year-on-year and month-on-month inflation rates since the CPI rebasing in August 2019. Indeed, the Government Statistician has said, “the average national inflation stood at 10.6%”. Food inflation (14.4%) outpaced non-food inflation (7.7%), especially in the two regions which were under COVID-19 partial lockdown; Greater Accra (20.8%) and Ashanti (18.2%).” This is a clear testament of how the COVID-19 restrictive measures have affected welfare of Ghanaians.

Interviews granted by citizens to the media indicated that many people in the areas affected by the partial lockdown became worse off during the three-week lockdown of economic activities. Aside from those in the informal economy, even many individuals who work in the formal but private sector had been rendered redundant with some being temporarily laid off.

Ghana’s Social Protection Response

Social protection systems, which include social insurance, social assistance, and labour market policies, function as critical safety nets for poor and vulnerable populations. A robust social protection system is a responsive or an adaptive one. Social protection systems should be able to build ex-ante preparedness of citizens to cope with shocks, as well as support shock response after experiencing a crisis (ex-post measures). Within social protection systems, various elements can be used to deliver a shock response – ranging from databases and registries, to delivery systems such as payment modalities.

The response of the Government of Ghana (GoG) to help alleviate the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the vulnerable households and individuals can be seen as both fiscal and pecuniary. Whilst it is too early to establish the real impact of these responses on welfare of vulnerable Ghanaians, all prevailing proof suggests that these measures should mitigate the negative impact of economic shocks.

Following the three-week partial lockdown, the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection (MoGCSP), and the National Disaster Management Organization (Ghana) (NADMO) embarked on the distribution of hot meals to vulnerable households and individuals in the partial lockdown areas. The Communications Director of NADMO, Mr. George Ayisi reported that the government spent GH₵ 2 million a day on the hot meals.

According to him, the state spent GH₵ 5.00 on each pack of food to feed over 400,000 under the social intervention program. While the government’s claim of providing 400,000 beneficiaries with hot meals is commendable, there are many vulnerable individuals and households across the country who are severely affected by the inherent shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, they fall outside the government’s social assistance radar.

Complementary to the government initiatives, faith-based organizations, corporate bodies, political parties, parliamentary candidates, and philanthropic individuals identified vulnerable individuals and households and supported them with relief items such as rice, milk, vegetable oils, assorted drinks, toiletries, hot meals, etc.

Another commendable response of the GoG that has been cushioning to citizens is the absorption of their utility bills. Indeed, this universal benefit includes the absorbing of water bills of all Ghanaians for April, May, and June 2020. It also covers a full or partial absorbing electricity bills depending on the household consumption. In his sixth address to the nation, on Thursday, April 9, 2020, the President stated that the government would fully absorb electricity bills for the poorest of the poor, i.e. lifeline consumers.

This will cover persons who consume 0 to 50-kilowatt hours per month. Other categories of consumers will enjoy a 50 percent discount within the same period. Although, this initiative has brought some relief to users of electricity, it has been more significant for poor families with exceedingly low income and the high marginal propensity to consume.

The Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection has availed evidence that payments to the beneficiaries of the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) Program continues amidst the coronavirus outbreak. The LEAP Program is a cash transfer scheme, which pays cash directly to the targeted poor beneficiaries, who include the disabled and elderly (over 65 years), as well as households with orphans and vulnerable children.

Generally supported globally, direct cash transfers are an effective way to provide social safety nets. Direct transfers to households are a key component of effective poverty reduction and development strategies. Joseph Hanlon, Armando Barrientos, and David Hulme have argued in “Just Give Money to the Poor: the Development Revolution from the Global South” that with direct cash transfers households make good use of transfers, transfers are effective in reducing poverty, transfers have longer-term benefits - human development, and they are also affordable.

UNICEF in a ‘Ghana COVID-19 situation report” of April 15, 2020, made the case that children in poor households are at increased risk of hunger and lack access to necessities as they are most vulnerable to economic disruption. These families may also take undue health risks in order to survive economically. UNICEF has shown interest in monitoring the situation of 330,000 vulnerable families who rely on regular cash transfers from the LEAP program.

Consequently, UNICEF has supported advance payments to LEAP households to minimize the economic impacts of prevention measures and enable them to practice good hygiene and social distancing practices. UNICEF has also stated that plans are underway to identify innovative delivery mechanisms to enable families to receive future payments safely and on time. In addition, LEAP communication channels will be leveraged to reach 1.5 million vulnerable people with accurate information and knowledge on infection prevention.

Social Protection Policy Options

As the GoG works to present a plan for public life and conduct in this crisis, the following clear action points are necessary.

- Social Protection Coverage Must Increase

Just like the absorption of utility bills by the GoG, the universal coverage of benefits will be appropriate for co-variate risks.

The number of beneficiaries of the LEAP Program should be increased and the benefit size indexed in keeping the prevailing inflation rates. The current beneficiary base of the LEAP Program does not cover ‘the new poor’ who suffer the loss of livelihood or earning opportunities because of lockdowns or social distancing, etc. The individuals and households who would have slipped below the poverty line due to the COVID-19 pandemic should be targeted for inclusion into the LEAP Program.

As huge public resources are channeled into social spending such as direct cash transfers, the GoG needs to enforce strict internal and external controls to minimize the fiduciary risks in respect of the payments of benefits. There have been reports of inclusion and exclusion errors in the selection of beneficiaries. This can erode the overall impact of the intervention. By increasing funding to LEAP from GH¢ 80 million in 2016 to GH¢223 million in 2019, the achievement of the program’s objectives may be hampered, if the beneficiary selection errors are not checked.

- Avoiding the Introduction of New Taxes

As much as the 3 months waiver on utility bills has been widely commended, an introduction additional taxes in this era of coronavirus pandemic would be high repugnant; and would even be counterproductive to the various social protection initiatives which seek to address vulnerability, risk, and deprivation. When a letter, from the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) dated May 4, 2020, on the Value Added Tax (VAT), the Ghana Education Trust Fund Levy (GETFund), and National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL) on energy and capacity charges, was misconstrued as the imposition of new taxes, the media, especially social media platforms were characterized by the furor. Consequently, the GRA withdrew the letter.

The Hon. Minister for Finance, Ken Ofori-Atta, in a statement to Parliament on Monday, March 30, 2020, on the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy of Ghana, stated that preliminary analysis of the macro-fiscal impact of the pandemic shows that there is likely to be a significant slowdown in GDP growth. He also indicated that the will be significant shortfalls in petroleum revenues, shortfalls in import duties, shortfalls in other tax revenues, with increased health expenditures, and tighter financing conditions. In an era where the government faces significant losses in revenues, a ‘daring government’ could take ‘backdoor’ means to impose new taxes.

- Increasing Public Education

A significant part of COVID-19 preparedness is the effective sensitization of citizens and communities to ensure that there is social behavioural adjustment relative to hygienic practices and especially, the new norms of social distancing. In Ghanaian communities, various notions and misinformation have gained currents of circulation. A conspiracy theory claiming coronavirus is caused by a 5G network has gained traction. Interestingly this myth has found some acceptability in sections of the population across both the developed and developing world; after a Belgian doctor linked the "dangers" of 5G technology to the virus during an interview in January.

It is compelling as part of measures by the government to resource the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) to effectively roll out a public sensitization program on the Coronavirus pandemic. Regrettably, the reports from the NCCE indicate that since January 2020, only a paltry GH¢ 100 (the equivalent of $17.00) was transferred to its district offices to help educate the citizenry on COVID-19. The commission lacks essential equipment including public address systems, recorders, vehicles, etc.

Although some District Assemblies are sponsoring public education through the district offices of the Information Service Department and other units, the need for vigorous public sensitization remains unfulfilled. The lack of timely and apt information, in a context of rigid societal norms, misconceptions, and misinformation about the pandemic, will assuredly increase people’s vulnerability.

- Encouraging Inter-Sectoral-Coordination

The government should harmonize COVID-19 social interventions and response initiatives across the various ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs). If there are no coordination mechanisms, the government’s initiatives may duplicate services and may generate needs gaps, poor referral outcomes, and confusion regarding how to draw benefits from the system. The relevant MDAs need to collaborate and harmonize programs for alleviating the adverse impact of COVID-19.

For instance, ministries of finance, employment, health, agriculture, gender, children and social protection, and state entities such as NADMO, security agencies (Immigration Service, the Police, Military, etc.) can integrate their efforts. Ghana’s social protection system must support citizens through better linkages with other sectors and services. It would be ideal if the Ministry of Agriculture could weave in some social assistance packages, in the form of agro-inputs to poor Ghanaian farmers.

- Credible Data Generation

The Ghana National Household Registry (GNHR) should consolidate and regularly update the database. GNHR is a unit under the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection with the mandate to establish a single national household register from which social protection programs in Ghana will pick their beneficiaries. Launched in October 2015, it is part of the efforts by GoG to sustain the progress made in poverty reduction by safeguarding that a larger share of benefits of social protection interventions goes to the extremely poor and vulnerable. The availability of reliable data of poor households will streamline and make more efficient the targeting of beneficiaries through proxy mean testing.

Indeed, best practices, conceptual frameworks, and remarkable documentation abound when it comes to social interventions. However, for these efforts to be converted into lasting structural changes, reliable data must be generated to inform policy choices. The GSS and allied institutions should document the impact of COVID-19 on poverty and inequality, as well as the impact of social protection systems on mitigating these effects. This becomes necessary to the extent that the post-COVID-19 period will require high social spending from the government.

The writer is a Social Protection Specialist and the Economic Governance Project Officer (EGPO) at Ghana Developing Communities Association (GDCA), Tamale, Northern Region. The views expressed here are strictly the author’s and do not reflect the position of GDCA.

By MOHAMMED MUSAH || [email protected]

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...