Where does the museum stand in relation to colonisation?

The principle of colonisation as a system of governance is fundamentally immoral and we completely distance ourselves from it. Royal Museum for Central Africa (1)

As readers know by now, there are in many European countries, especially in the former colonial powers that dominated the countries of Africa for uncounted decades, Great Britain, Germany, France, and Netherlands discussions on the question of the restitution of looted African artefacts. The colonial masters who were to bring us civilization, according to their own accounts, looted not only mineral resources-gold, bauxite, diamonds-timber and took away human beings for slavery, but also stole uncountable quantities of African artefacts that now decorate many private European homes and are boldly displayed, without shame or fear, in the major museums in London, and Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussel, Leiden, Paris, and Vienna. One country that seems to be left out in the current restitution debates seems to be Belgium. This is surprising considering that under the Belgian king, Leopold II, the Congo which was run like a private company of the king, Africa experienced one of the cruellest colonial regimes (and colonial regimes are by definition racist oppressive systems operated by Europeans against Africans). The atrocities of the Belgian king have been well narrated by Adam Hochschild in his King Leopold’s Ghost. (2) That nefarious regime also stole thousands of African artefacts and human remains from the Congo. Now an international group of intellectuals and activists, including many persons from the African diaspora, have signed an open petition on 25 September,2018, to the Belgian government and authorities requesting the restitution of looted artefacts and the return human remain to the Congo. (3) Most of the stolen/looted artefacts from the Congo are kept in the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren (4)

A giant golden statue of a European missionary with an African boy clutching his robes is seen at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, near Brussels, January 22, 2014. Francois Lenoir/File Photo. A plaque reads ‘Belgium bringing civilization to Congo

The petitioners of the open letter are asking from the government for the following:

- That the government through its Secretary for Scientific Policy to take out of state ownership, property that is known to have been acquired through looting, theft and murder, starting with the storms collection;

- Restitution of treasures stolen from Africa as well as human remains from colonial massacres;

- A moratorium on the opening of the Museum and the exhibition of objects known to have been acquired by theft, looting, forced conversion etc;

- Restitution of human remains without DNA tests;

- Support for the establishment of an opinion tribunal or an independent commission to investigate the colonial crimes of Storms and others;

- The appointment of a group of multidisciplinary experts, including Belgians from African diasporas who will develop a restitution plan;

- Publication of educational materials on colonial policy and the notion of restitution.

- The organization of an international conference on restitution;

- That justice be done and that reparations including financial reparations be guaranteed;

- That official apologies are declared by the highest authorities the Belgian State.

Following the open letter, there was on 16 October 2018 a debate on Restitution of African cultural properties: moral or legal question? in the French-speaking Parliament in Brussels under a combined leadership of the president of the assembly and the Belgian Afro-Descendants Muntu Committee, BAMCO-CRAN. The debate held at the invitation of a large majority of members of the Brussels Capital Region,72 out of 89 parliamentarians will be followed by the constitution of a group of experts as well as a resolution to be shared with other parliaments in Belgium. Proposals will be made to amendments of the law to enable restitutions. (5)

The open letter has already prompted a group of scholars and university personnel, some of them museum officials working in the Royal Museum for Central Africa, to issue a statement on 17 October 2018 calling for a transparent dialogue that must prevail over paternalism. They reject the usual manoeuvring of European museums to avoid concrete issues. As a contribution to the current debate, the participants in a forum of 17 October 2018 made the following points:

1. In this debate, no significant dialogue is possible today on the basis of legal arguments. Several collections of museums were ‘reassembled’ Long before the emergence of legislation concerning international conflicts, human rights and the protection of cultural property. The fact that we do not have retroactive legislation today testifies to the very unequal power relations between the North and the South.

2. Un undeniable moral argument in favour of restitution derives from the fact that a large majority of the patrimony of Congolese art is in Western museums and in private collections. This means that most Congolese today have no access to this patrimony. Given that art, patrimony are important landmarks for emancipation and development, an eternal status quo becomes morally indefensible from this point of view.

3.Moreover, there is an important historical argument. Already during the colonial period, there were Congolese demands for the return of objects and at the time of independence voices were raised in favour of the return of cultural patrimony. On the side of the Congolese there was double insistence on the necessity of having control of natural resources as well as on cultural riches. Even though one likes to say that colonialism has been behind us for a long time, the depositary of the great majority of the cultural patrimony of Congolese art shows the contrary, despite many numerous demands for restitution since independence.

4. We call for an open dialogue where all demands for restitution are seriously and respectfully received. It must be admitted that ‘restitution’ concerns primarily the physical return of the museum object. Digitalization, loans and travelling exhibitions are equally important but they should not deviate from the central issue of the debate. The uncertainties or preoccupations concerning the practical aspects of restitutions (choice from collections, recipients, how to etc.) should not impede this dialogue. If necessary, the legal framework must be modified. Respectful listening must take precedence over paternalism.

5.The museums must offer more transparency concerning facts on the provenance of objects they hold. This information must be accessible also to non-professional researchers, and in particular to Africans and the African diaspora.

6. Belgium must adopt general directives for the sector of museums concerning the handling of colonial collections. We could follow the example of the German Museum Association and the specialists designated in France. These general directives should be adopted within a period of one year.

7.There is a need for more detailed research in Belgian museums and universities on the exact provenance of museum objects. Following the examples of research units in our neighbouring countries Belgian authorities must provide additional funds for ambitious research programmes concerning the provenance of collections and possible strategies for restitutions. This research must be done in Belgium but also especially in Africa Such research units must be operational in a period of two years and must develop concrete plans pour real restitutions.

8. The museums must develop a policy of active restitution regarding human remains from Congo and other former colonies There must be a proactive policy: the museums must take themselves the initiatives to find appropriate solutions by way of consultation This restitution must be achieved within five years. (6)

But what are the chances of these demands from both the open letter, the debate in the Francophone parliament and from the forum being accepted and implemented by the Belgian authorities? Given the fact that the Belgians have before them the examples of Germany, which is not encouraging for restitution, (7) the French approach which promises to result in restitutions, (8) and the Anglo-German-Austro-Dutch approach which turns history, justice, and morality upside down in a neo-colonialist loan to the deprived former colonies, (9) the Belgians have a wide variety of models.

The Minister for Co-operation, Alexander de Croo, has said he is willing to discuss with authorities, museum directors and experts from the countries involved. (10)

The Royal Museum for Central Africa, now called Africa Museum has indicated at its homepage that it has now adopted a progressive outlook. This will be put to test when it reopens on December 8 and proceeds to consider the demands made above. Meanwhile, the museum proclaims the following:

‘What is the museum’s position as regards the return of African cultural heritage?

The presence of African collections in Tervuren inevitably leads to the issue of returning these objects to their country of origin.

We are open-minded, participate in ongoing discussions within an international context and get involved in discussions relating to the future of African cultural heritage, which are currently being held in Europe.’ (11)

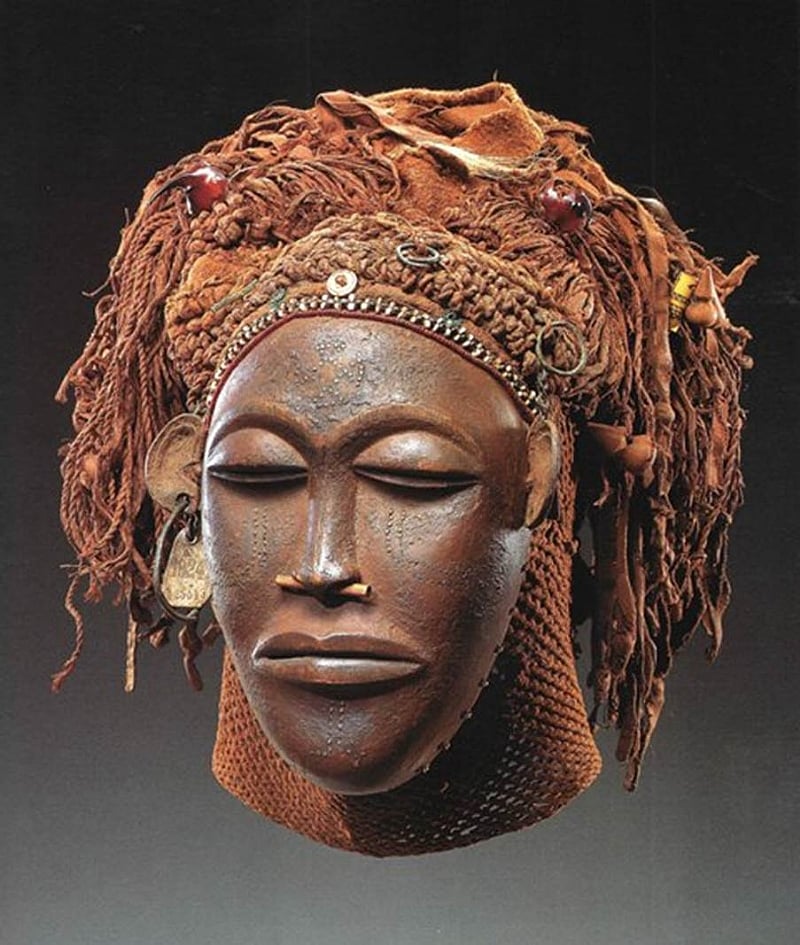

Phwo mask. Tshokwe. Mwakahila, South Kasai, Zaire, now in Africa, Tervuren, (, formerly Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium)

After this proclamation, the reader is invited to take a look at the online collection of the museum. I was shocked by the presentation. Apart from the usual ethno-colonialist presentation of Africans, there is a photo captioned Actors of Congolese Independence. And who is shown in the picture? Mobutu. Where is Patrice Lumumba?

.

This image alone raises doubts about lofty pronouncements of the museum on its abhorrence to colonialism and its open mind regarding restitution and its distancing itself from Leopold II as governor as governor of the Congo. Can we trust the museum to convey the true history of political and social development in Congo? Given the exquisite Congolese artefacts that the museum is holding, one is surprised by its choice of images that are more appropriate for showing Africans at a certain low level of development.

Guido Gryseels who was director of the Royal Museum and is now director of the Africa Museum, seems to have undergone some changes in his thoughts about restitution of the looted Congolese artefacts. When some years ago we examined his writings, we got the distinct impression that he was not in favour of restitution of looted African artefacts. In a UNESCO report of the Conference on the Return of Cultural Objects, the Athens Conference, 17-18 March 2008, we read as follows:

“Guido Gryseels, the Director of the Tervuren Museum, shared his views on the return of cultural heritage artefacts. According to Gryseels, museums have to improve the accessibility of their collections, both for scholars and the general public, by digitizing their collections so that they can be viewed on line and by creating databases and virtual museums. Discussions relating to the physical locations where collections are displayed will then assume less importance. However, a blanket return of all cultural heritage is deemed out of the question. No objects can be returned to their country of origin before these countries have acquired political stability and basic infrastructure. From this point of view the return of artefacts would seem impossible at the moment. (12) Gryseels added also that only “duplicates” could be returned in the foreseeable future. Is political stability an issue for museum directors or is it just a convenient excuse for delaying restitution?

Gryseels now sounds a little more accommodating to demands for restitution, especially after the initiative of President Macron. In an interview published in Le Monde under the significant title L’Afrique a été pillée, he admits that Africa has been plundered by the European States and that this factor cannot be ignored. His museum is open to discussion of the question of restitution, he suggests there should be an international conference to settle the issue. (13) We have in several articles pointed out that there is no need for an international conference on the issue of restitution. We have already had such conferences, eg.in 1958. Besides, there have been several United Nations/UNESCO resolutions urging States holding African artefacts to return them to their original owners. (14)

Gryseels on radio and television appears progressive but he basically remains in the neo liberal scheme-yes to restitution, but do you have secure and adequate museums, do you have sufficiently qualified personnel, what about conservation methods? You should not discount training, exchange of information etc. Gryseels, from all that we have read or heard from him appears to take on restitution a similar position to that of many of our liberal museum directors and intellectuals. They are all for restitution but subject to certain conditions. But do successors to looters have the right to impose conditions for returning undoubtedly looted objects? There is something neo-colonial about all these attempts to tell Africans what to do with their treasures.

When these objects were looted, they were not in museums and there is no reason to insist on our having to put them in museums. We might decide to put them in palaces of kings and chief in the areas from which they were looted. Europeans and other Westerners have no right to seek to impose on Africans their cultural ideas. They cannot insist that we put most of the returned looted artefacts in a museum in the capital city, preferably planned, built and financed by them, supervised by personnel they have trained. That is undoubtedly neo colonialist and racist vision of life and culture. Africans have our own conceptions of culture and development. Our artefacts were created without instructions and advice from Europeans who looted them some hundred or more years after their production.

Apparently, many Westerners still believe in the foolish racist idea of the European Enlightenment that the Europeans are at the top of the scale of human development and that all other peoples have to follow them. What Asia and Africa seem to them to be irrelevant and some Africans have imbibed this ideology and are not able or unwilling to think of any independent development for their societies even when historical evidence demonstrates independent development of Asian and African societies.

Ngaady aMwaash Mask of the Kuba people, Democratic Republic of Congo, now in Africa Museum, Tervuren, Belgium (formerly Royal Museum for Central Africa)

Evidently, we cannot put Gryseels and the liberal museum directors in the same category as those who oppose restitution in principle such as Julien Volper, a conservator at the Africa Museum at Tervuren and Lecturer at the Centre for Cultural Anthropology, at the Free University, Brussel who wrote in Le Figaro under the significant title’ Let us defend our museums! Volper stated that there in France and elsewhere persons who are waiting the turn the museums into tombs and empty them of their collections. (15) In the end effect though, one may legitimately ask whether there is much difference between those who reject restitution categorically and those who declare they accept restitutions but then set conditions that may not always be easy to fulfil-modern museums, trained personnel, modern security etc.

Drum, Democratic Republic of Congo, now in Africa Museum Tervuren, Belgium

What worries me about the various attempts to be made to change the nature of the museum from a colonial museum to a museum that depicts contemporary Congo is the idea that one can retain obvious racist colonial sculptures and give them a new context (16) The golden statue of a European missionary holding an African child with a plaque reading: “Belgium brings civilization to Congo”, is to remain on show, but its historical context will be explained. This is a devious procedure. Can one simply provide any new interpretation of a work of art to suit any changed circumstances? Would an honest approach not be to remove the statue and replace it by another? The artist who made the criticised object must have had a definite intention and had produced what he thought expressed his understanding. Can anybody come decades later and attribute to the artist intensions he did not have in mind? Can you really interpret differently a sculpture intended to praise Belgian missionary work and make it say something else, contrary to what the statue has always stood for during decades? Can the unwillingness to part with the racist statute indicate an unwillingness or inability to make a clean break with the cruel Belgian colonial rule in Congo?

In an interview in 2014, Gryseels admitted that balancing the requirements of a modern perspective of Africa and retaining some of the objects in the museum, such as the leopard, a native wearing a fierce mask and ready to pounce on his sleeping victim would be difficult. But he added:

“We will be very critical, but what we want to do is provide the elements to the visitor so that he can make up his own mind. There are a lot of good things that happened too…What was realized in terms of infrastructure, roads, airports, ports, education, health facilities, research, is really quite incredible,” (17)

Can the museum proclaim its abhorrence of Leopold’s cruel regime and still maintain sculptures that have contributed to hiding the truth of the inhuman regime that cut hands and fingers of children from areas that did not produce enough rubber as the colonial masters wanted? Either the museum wants to break with this cruel past or not. It cannot have it both ways. If one adopts the underlining reasoning of Gryseels one can find good in every evil deed or person. How would Europeans react if Germans put a statue of Adolf Hitler in a new museum in Germany saying certain good things were achieved during the terror regime of Hitler? Would one say this to the victims of the evil Nazi regime? You could even find something good in the transatlantic slavery by pointing out the very fine musicians and culture we find in the USA and in the Caribbean. But would anyone dare to make such a horrible statement to African-Americans? The museum must break away from the evil regime it has said was ‘fundamentally immoral’. Even the roads and infrastructure that was built in the Congo was with slave labour and African workers paid starvation wages.

When the Africa Museum at Tervuren opens on 8 December 2018, the report of Benedict Savoy and Felwine Sarr would have been published and the pressure on Belgium and the Africa Museum would be tremendous. The usual arguments Western museums use to deny restitution of African artefacts looted under colonial rule would be untenable and unsustainable and would be shown to be what they have always been: self-serving arguments for a racist, cruel and oppressive colonial regime, whose greed and cruelty knew no bounds.

After all that we know about colonial oppression, the fact that Europeans are still arguing with Africans about restitution of African artefacts looted by Europeans should really shame our contemporary Europeans.

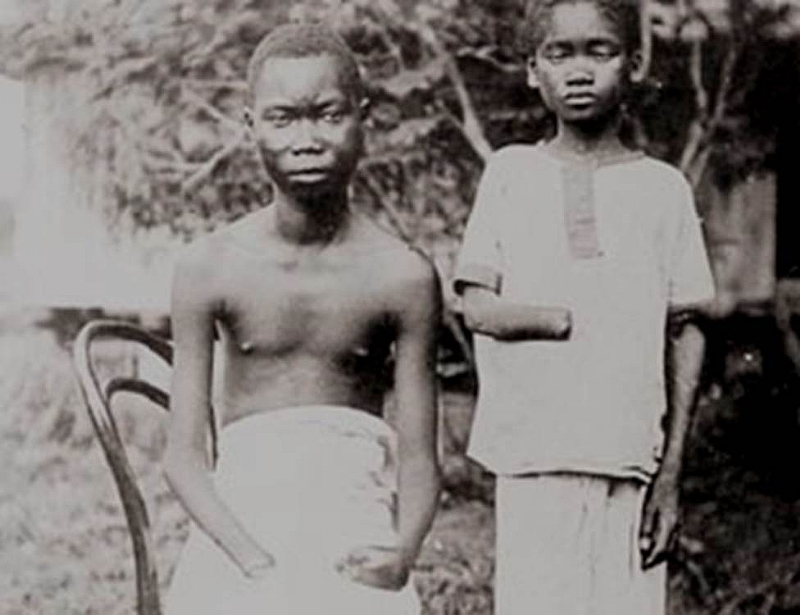

Children with their hands cut The Hacked Hands of the Belgian Congo - Lisapo yaw Kama en.lisapoyakama.org/the-hacked-hands-of-the-belgian-congo/ (18)

It is worth reiterating that Western collecting of African cultural artifacts are literally records of violence against African indigenous cultures. The removal, and frequently destruction, of indigenous artefacts’ were meant to sever the bonds that held most cultures together, thus making them available for colonial indoctrination. They also represented a massive plunder of indigenous wealth. As repositories of the plunder of the globe by Western countries in the past four centuries, Western museums face major questions about their role in contemporary culture, especially as indigenous peoples worldwide emerge into globalization to demand repatriation of important cultural artifacts, and restitution for the impact of the removal of such artefact’s on their societies’.

Sylvester Ogbechie (19)

Kwame Opoku.

Female Figure Holding a Bowl, Luba Peoples, Democratic Republic of Congo, now in Africa Museum, Treveon, Belgium, (formerly Royal Museum for Central Africa))

NOTES

1. Myths and taboos about the museum - Royal Museum for Central Africa www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/myths_taboos

2.The reader will benefit from reading Adam Hochschild’s account of the Belgian King Leopold’s oppressive and cruel rule in the Congo: King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa,1999.

King Leopold's Ghost – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Leopold%27s_Ghost Those with strong stomachs can also read the article on Leopold II in Wikipedia where it is stated that “A result of Leopold's colonialism, children had their hands amputated when they didn't meet demands for the Belgians” A photo of two children with amputated hands is shown there. http://en.wikipedia It has been said of the Tervuren Museum in connection with its exhibition in 2005, The Memory of Congo: the Colonial Era and Congo: Nature and Culture: that: “The museum has come to represent the worst abuses of Belgian colonialism in Africa, though in touring Brussels, visitors can see other vestiges of Congo's plundering. Ivory, rubber, copper, diamonds and gold from the Central African nation, now called the Democratic Republic of Congo, funded the construction of the broad Parc du Cinquantenaire and the colossal neoclassic Palais de Justice. And everywhere in the Belgian capital there are statues of King Leopold II, whose stated purpose in Congo was to "bring civilization to the only part of our globe it hasn't yet penetrated." Along the way, the king, who died in 1909, reaped a profit from the colony of an estimated $1.1 billion.” http://users.telenet.be

3. Carte blanche: la Belgique est à la traîne sur la restitution des trésors ... https://plus.lesoir.be/.../carte-blanche-la-belgique-est-la-traine-sur-la..

See Annex I for the original text.

Martin Vander Elst – Bruxelles Panthères

https://bruxelles-panthere.thefreecat.org/?tag=martin-vander-elst

RESTITUER A L'AFRIQUE SON PATRIMOINE | Mémoires du Congo www.memoiresducongo.be/afrique-patrimoine/

4. Home | Royal Museum for Central Africa - Tervuren - Belgium

www.africamuseum.be/en/home

Royal Museum for Central Africa - Wikipediahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Museum_for_Central_Africa

5. Belgique: la restitution du patrimoine africain en débat - RFI

www.rfi.fr/.../20181102-belgique-restitution-patrimoine-africain-de...

6. Carte blanche: Le dialogue sur les trésors coloniaux doit l'emporter ...

7. K. Opoku, Germany's Answer to Macron on Restitution Of African Artefacts ...

8. [PDF]. macron promises to return african artefacts held in french museums-1

www.no-humboldt21.de/wp-content/uploads/.../Opoku-MacronPromisesRestitution.pd...

9 . Nigeria To Borrow Looted Nigerian Artefacts from Successors Of ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../nigeria-to-borrow-looted-nigerian-artefacts-from-s...

10. Belgique: la restitution du patrimoine africain en débat - RFI

11. Myths and taboos about the museum - Royal Museum for Central Africa

12. Museum International, UNESCO, nos. 241 and 242, May 2009, Return of Cultural Objects - Athens Conference, p. 24.

Would Western Museums Return Looted Objects If Nigeria And Other ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../would-western-museums-return-looted-objects-if-ni...

13. Restitution d’œuvres : « L’Afrique a été pillée, nous ne pouvons pas l’ignorer pillee-

14. Resolutions adopted by the United Nations General ... - UNESCO

www.unesco.org/.../restitution.../resolutions-adopted-by-the-united-nations-general-asse... t

The United Nations has since 1972, almost on a biennial basis passed resolutions urging holding States to return cultural property to their country of origin but Western States have paid very little attention to these resolutions.

See also, Kwame Opoku - PARZINGER'S CRI DE COEUR: GENUINE PLEA FOR UN ...

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/museum_security_network/...

15. Défendons nos musées! - Le Figaro www.lefigaro.fr › VOX › Vox Société

16. King Leopold's ghost: Belgium's Africa museum to reopen | Reuters

https://www.reuters.com/.../king-leopolds-ghost-belgiums-africa-museum-to-reopen-i..

17. The Hacked Hands of the Belgian Congo - Lisapo ya Kama en.lisapoyakama.org/the-hacked-hands-of-the-belgian-congo

The treatment of human remains as well as the human body in Belgian colonial history and the incompetent handling of the issue of human remains today is so horrible and incredible that I prefer not to deal with it. I do not have the stomach to handle this and I therefore refer the reader to the articles by Michel Bouffioux entitled Collections coloniales de restes humains and I feel there is little hope for mankind when he writes: ‘Alors qu’en Belgique, des jeunes chantent encore d’horribles chansons coloniales écrites la gloire des coupeurs de mains et autres tortionnaires qui travaillèrent au service de l’Etat indépendant du Congo, il serait peut-être bon d’ouvrir un vrai débat politique à propos de ce qu’il convient de faire de ces restes humains’.

Paris Match.be : "Le crâne de Lusinga interroge le passé colonial belge"

www.lusingatabwa.com/.../paris-match.be-le-crane-de-lusinga-inter

Collections coloniales » de restes humains : l ... - Michel Bouffioux

www.michelbouffioux.be/.../collections-coloniales-de-restes-humai...

Collections coloniales de restes humains : Le gouvernement ...

https://parismatch.be/.../collections-coloniales-de-restes-humains-le-.

The skull of Chief Lusinga who refused to submit to Belgian colonial rule and was decapitated on 4 December 1884 by Emile Storm, Belgian commander. The skull is still in Belgium It is part of the ‘anatomic anthropology collection’ which includes 289 skulls,12 foetus and 8 skeletons and other remains that were transferred in 1964 to the’ Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique (IRSNB) in Brussels. There is in Meeus Square in Brussel a statute celebrating Emile Storms. See Michel Bouffioux

18. John O’Donnell, Colonial ghosts haunt Belgium as Africa museum eyes change, Colonial ghosts haunt Belgium as Africa museum eyes change | Reuters https://www.reuters.com/...belgium...museum/colonial-ghosts-haunt-belgium-as-africa-m...

19. Sylvester,Ogbechie, The Postcolonial African Museum in the Age of CulturalInformatics

Annex I

Carte blanche: la Belgique est à la traîne sur la restitution des trésors coloniaux

Mis en ligne le 25/09/2018 . Par Un collectif de signataires*

Illustration de Guy Atafo.

Plus de 90 % des œuvres d’art classique africain sont en dehors de l’Afrique. Pillées pendant la colonisation, elles se trouvent désormais au British Museum, au Musée du Quai Branly, ou au Musée de Tervuren. Les Africains du continent qui désirent montrer leur patrimoine à leurs enfants ne le peuvent pas. Tout ou presque a été dérobé. On ne saurait fonder le dialogue interculturel sur des pillages précédés par des meurtres coloniaux : les biens volés doivent être restitués.

Qu’est-ce que la Restitution ?

On entend par « Restitution » le fait de « remettre » ou de transférer des objets culturels volés ainsi que des restes humains emportés dans les pays occidentaux lors de guerres coloniales. Mais cette Restitution ne se résume pas au retour physique des objets en Afrique, elle peut prendre des formes diverses. Il s’agit d’une question morale, bien sûr, mais aussi d’économie, étant donné que ces biens sont une base nécessaire pour développer le tourisme. D’ailleurs, la Banque mondiale affirme que le tourisme sera la première industrie au 21e siècle, et que les pays africains doivent s’y préparer. On peut bien sûr se demander comment développer le tourisme culturel, quand tout le patrimoine culturel a été emporté, mais surtout on souhaite affirmer que la Restitution est aussi une question de droit national et international.

Vol, recel et blanchiment de biens… et de restes humains

Récemment, une enquête du journaliste Michel Bouffioux a révélé que quelque 300 crânes et autres ossements provenant de « collectes coloniales » réalisées principalement au Congo, sont actuellement conservés en Belgique. Les conditions d’acquisition de ces restes humains sont peu ou pas documentées, des archives ont été « égarées ». Lorsqu’il est possible de retracer le parcours de certains de ces ossements, comme l’a fait le journaliste, on découvre des histoires comme celle du militaire belge Emile Storms. En 1884, alors qu’il conquérait des territoires au profit d’une organisation privée présidée par Léopold II, cet officier commandita l’exécution de plusieurs chefs coutumiers jugés trop peu collaborants. Les villages des récalcitrants étaient incendiés. Des biens culturels étaient volés, notamment ces statuettes qui appartenaient au chef Lusinga et qui font actuellement partie des « trésors » du Musée Royal de l’Afrique centrale à Tervuren. Storms faisait aussi « collection » (le terme est de lui) de têtes de chefs décapités. Il ramena trois crânes en Belgique, dont celui du chef Lusinga, qui servirent à des exposés pseudo-scientifiques sur la supériorité de la race blanche. En 2018, ces crânes sont toujours conservés par le Musée des Sciences naturelles à Bruxelles.

A l’égard de ces restes humains, l’avocat Christophe Marchand a évoqué un « recel de dépouilles mortelles de personnes assassinées », ce qui est condamné par l’article 340 du Code pénal d’une peine de trois mois à deux ans de prison. Le même raisonnement peut s’appliquer aux objets culturels volés. Le même raisonnement peut s’appliquer aux objets culturels volés. L’avocat, aborde aussi la notion de « blanchiment », qui tient compte des dommages subis dans le temps long par les peuples colonisés (cf. La Proclamation d’Abuja, 1989), mais aussi des avantages tirés des crimes coloniaux par les puissances colonisatrices. En droit, le blanchiment peut être défini comme le « fait de prendre possession, de gérer ou de transformer en objet particulier le “produit” d’une infraction pénale. En effet, si un bénéfice est tiré du vol, d’un assassinat ou d’un pillage, la gestion financière de cet avantage patrimonial est elle-même une infraction. » En outre l’infraction de blanchiment est imprescriptible, car elle se répète à chaque acte de gestion dudit avantage. De quoi interpeller le Musée Africain de Namur, le Musée Royal de Tervuren qui détiennent des objets, mais aussi le Musée des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique ainsi que l’Université Libre de Bruxelles où sont stockés des crânes et des ossements de congolais assassinés par décapitation ou suite à des tortures, parce qu’ils refusaient d’être colonisés.

Et, lorsque 60 % environ du patrimoine du MRAC s’est constitué pendant l’époque coloniale, la question du vol, du recel et du blanchiment se pose et ne laisse que très peu de doutes pour certaines collections.

La Restitution : partout sauf en Belgique ?

Depuis quatre ans, le CRAN (Conseil Représentatif des Associations Noires), ONG internationale, se bat pour la Restitution des trésors africains. Ce combat n’a pas été vain. En novembre 2017, se trouvant à Ouagadougou, le Président Macron a déclaré : « Le patrimoine africain ne peut pas être uniquement dans des collections privées et des musées européens. Il doit être mis en valeur à Paris, mais aussi à Dakar, Lagos, Cotonou (…). Ce sera une de mes priorités. D’ici cinq ans, je veux que les conditions soient réunies pour un retour du patrimoine africain à l’Afrique. » Depuis lors, le président français a nommé deux experts pour mettre en œuvre la décision annoncée. La dynamique lancée ces dernières années par plusieurs mouvements dont le CRAN continue en Allemagne où des restes humains ont été restitués à la Namibie ainsi qu’en Angleterre, où les autorités songent désormais à restituer à l’Ethiopie un certain nombre de biens culturels de grande valeur. Le Canada a aussi entamé un vaste programme de Restitution depuis 1997. Nous ne pouvons ignorer la dynamique internationale qui est en cours, et faire comme si la question de la Restitution se posait partout, sauf en Belgique.

Objections votre honneur !

En nous lisant, vous pensez peut-être que « le Congo n’a pas d’infrastructures nécessaires à la conservation de ses propres œuvres précieuses » . Ce serait du paternalisme aux relents coloniaux de penser cela, or, vous nous accorderez que de nombreux pays africains possèdent des musées modernes et équipés et que des accords de conservation et de sécurisation entre pays africains ou avec des pays occidentaux sont possibles. Enfin, est-ce vraiment aux pays qui ont brûlé et détruit des objets culturels pendant les guerres coloniales de donner des leçons sur la sécurité et le respect dû aux œuvres d’art en Afrique ?

Ce que nous demandons :

- Que le gouvernement, via sa Secrétaire à la Politique scientifique, sorte de la propriété de l’Etat des biens dont on sait qu’ils ont été acquis par les pillages, le vol et le meurtre ; en commençant par la collection Storms.

- La Restitution des trésors volés à l’Afrique ainsi que des restes humains issus des massacres coloniaux.

- Un moratoire sur la réouverture du Musée et l’exposition des objets dont on sait qu’ils ont été acquis par le vol, le pillage, la conversion forcée, etc.

- La Restitution des restes humains sans exigence d’effectuer des tests ADN

- Le soutien à la mise en place d’un tribunal d’opinion ou d’une commission indépendante chargés d’instruire les crimes coloniaux de Storms et des autres.

- La nomination d’un groupe d’experts pluridisciplinaires, dont des Belges issu.e.s des diasporas africaines qui élaboreront un plan de Restitution.

- La publication de matériels pédagogiques sur l’histoire coloniale et la notion de Restitution.

- L’organisation d’une conférence internationale sur la Restitution.

- Que la justice soit rendue et que des Réparations notamment financières soit garanties.

- Que des excuses officielles soient prononcées par les plus hautes instances de l’Etat belge.

- Puisse le Royaume de Belgique se saisir de l’opportunité que nous lui offrons pour faire preuve de son sens de l’histoire, en réaffirmant sa dignité et son humanité par ces actions qui sont le propre des grandes nations.

*La liste des signataires : Ilke Adam, professeure, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Gia Abrassart, journaliste à Café Congo et co-fondatrice de Warrior Poets, Rachida Aziz, écrivaine et fondatrice du Space, Hamza Belakbir, rédacteur en chef, revue Politique Web, Mustapha Chairi, président du Collectif contre l’Islamophobie en Belgique, Véronique Clette-Gakuba, chercheuse à l’Université Libre de Bruxelles, Heleen Debeuckelaere, auteure et historienne, Tahir Della, Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland (ISD-Bund), Matthias De Groof, chercheur à Helsinki University, Sarah Demart, chargée de recherche à l’Université de Saint-Louis Bruxelles, Ludo De Witte, auteur, Georgine Dibua Mbombo, coordinatrice Bakushinta, Marie Godin, chercheuse à l’Université d’Oxford, Charles Didier Gondola, professeur à Indiana University – Purdue University, Nicole Grégoire, chercheuse, chargée de recherche au FNRS, Université libre de Bruxelles, Sa Majesté la Reine Diambi Kabatusuila (Kasaï/RDCongo), Sibo Kanobana, chercheur à l’Université de Gand, Christian Kopp, Berlin Postkolonial, Mnyaka Sururu Mboro, NGO alliance ‘No Humboldt 21 !’, Anne Westi Mpoma, historienne de l’art, Laura Nsengiyumva, artiste et chercheuse à KASK à l’Université de Gand, Modi Ntambwe, fondatrice de ArtDéCycles, galerie itinérante, Jacinthe Mazzocchetti, enseignante-chercheure à l’Université catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve, Monique Mbeka Phoba, réalisatrice et productrice de films, Toma Muteba Luntumbue, Historien de l’art, Professeur à l’Erg Ecole de Recherche graphique et à La Cambre, Jean Muteba Rahier, Professeur à Florida International University, Maître Brice Nzamba, Avocat au Barreau de Paris et conseil de BAMKO-CRAN, Nel Tsopo Nziemi, rédacteur en chef de Brukmer magazine, Charlotte Pezeril, chercheure à l’Université Saint-Louis, Mireille-Tsheusi Robert, Présidente de BAMKO-CRAN asbl, Allen F. Roberts, Professeur à l’Université de Californie/ Los Angeles, Louis-Georges Tin, Premier Ministre de l’Etat de la Diaspora Africaine, Joseph Tonda, professeur à l’université Omar Bongo de Libreville au Gabon, Martin Vander Elst, chercheur au Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Prospective à l’Université catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve (aspirant FNRS), Bob White, professeur à l’Université de Montréal, André Lye Yoka, Directeur Général de l’Institut National des Arts (INA-Kinshasa-RD-Congo), Sa Majesté le Roi Tchiffi Zié, S.G. du Forum International des Souverains et Leaders Traditionnels Africains

Annex ll

Carte blanche : Le dialogue sur les trésors coloniaux doit l’emporter sur le paternalisme

https://www.lesoir.be/185112/article/2018-10-17/carte-blanche-le-dialogue-sur-les-tresors-coloniaux-doit-lemp

Dans l’espoir d’apporter une contribution positive au débat sur les collections du Congo, nous voudrions faire les remarques suivantes :

1. Dans ce débat, aucun dialogue significatif n’est possible aujourd’hui sur la base d’arguments juridiques. De nombreuses collections de musées ont été « rassemblées » bien avant l’émergence d’une législation relative aux conflits internationaux, aux droits de l’homme et à la protection du patrimoine culturel. Le fait que nous n’ayons pas de législation rétroactive aujourd’hui témoigne des relations de pouvoir encore très inégales entre nord et sud.

2. Un argument moral indéniable en faveur de la restitution découle du fait que la grande majorité du patrimoine d’art congolais se trouve dans des musées occidentaux et des collections privées. Cela signifie que la plupart des Congolais n’y ont pas accès aujourd’hui. Etant donné que l’art, le patrimoine, et l’histoire sont des repères importants pour l’émancipation et le développement, un statu quo éternel devient de ce point de vue moralement indéfendable.

3. De plus, il existe un argument historique de poids. Déjà pendant la période coloniale, il y avait des demandes congolaises pour un retour d’objets et au moment de l’indépendance, des voix se sont élevées en faveur d’une restitution du patrimoine culturel. Du côté congolais on a insisté sur la double nécessité d’avoir la maîtrise des richesses naturelles aussi bien que des richesses culturelles. Bien que l’on aime dire que le colonialisme est derrière nous depuis longtemps, le dépositaire de la grande majorité du patrimoine d’art congolais montre le contraire, en dépit de nombreuses demandes de restitution depuis l’indépendance.

4. Nous appelons à un dialogue ouvert où les demandes de restitution sont reçues avec respect et sérieux. Il faut que l’on admette que ‘restitution’ concerne principalement la restitution physique d’objets de musée. La numérisation, les prêts et les expositions itinérantes sont également importants, mais ne doivent pas détourner l’attention du cœur du débat. Des incertitudes ou des préoccupations concernant les aspects pratiques des restitutions (choix des collections, destinataires, comment faire, etc.) ne doivent pas entraver ce dialogue. Si nécessaire, le cadre législatif doit être ajusté. Écouter avec respect doit prendre le pas sur le paternalisme.

5. Les musées doivent offrir plus de transparence concernant les données sur la provenance d’objets dont ils disposent eux-mêmes. Cette information doit être rendue accessible aussi aux chercheurs non-professionnels, en particulier aux Africains et à la diaspora africaine.

6. En Belgique, des directives générales doivent être adoptées pour le secteur des musées concernant la gestion des collections coloniales. Nous pouvons suivre l’exemple de l’association allemande des musées et des spécialistes désignés en France. Ces directives devraient être adoptées dans un délai d’un an.

7. Au sein des musées et universités belges, il existe un besoin de recherche plus approfondie sur la provenance exacte d’objets de musée. A l’instar des unités de recherche dans nos pays voisins, les autorités belges devraient libérer de nouveaux moyens pour des programmes de recherche ambitieux relatifs à la provenance des collections et des stratégies possibles pour des restitutions. Cette recherche doit être menée en Belgique mais également et surtout en Afrique. De telles unités de recherche devraient être opérationnelles dans un délai de deux ans et développer des plans concrets pour des véritables restitutions.

8. Les musées doivent développer une politique de restitution active relative aux restes humains provenant du Congo et d’autres anciennes colonies. Il faut une politique proactive : les musées doivent prendre eux-mêmes des initiatives pour trouver des solutions appropriées par la voie de la concertation. Cette repatriation doit aboutir dans un délai de cinq ans.

*Ces propositions sont appuyées par les personnes suivantes qui s’expriment à titre personnel : Bénédicte Ledent, Université de Liège ; Benedikte Zitouni, CES/Université Saint-Louis, Bruxelles ; Berber Bevernage, UGent ; Charlotte Pezeril, Université Saint-Louis, Bruxelles ; Daniël Biltereyst, UGent ; Eline Mestdagh, UGent ; Elke Mahieu, UGent ; Elke Selter, School of Oriental and African Studies (Londres) ; Els De Palmenaer, MAS Antwerpen ; Filip De Boeck, IARA/KULeuven ; Gillian Mathys, UGent ;Hannelore Vandenbergen, AfricaMuseum, Tervuren ; Hein Vanhee, AfricaMuseum Tervuren & UGent ; Hugo DeBlock, UGent & KASK Gent ; Ilke Adam, VUB ; Jacinthe Mazzocchetti, UCLouvain ; Jean-Luc Nsengiyumva, CES/Université Saint-Louis, Bruxelles ; Johan Lagae, UGent ; Jos van Beurden, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam ; Joséphine Vandekerckhove, UGent ; Julie Lambrechts, FARO ; Karel Arnaut, IMMRC, KU Leuven ; Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse, KULeuven ; Katrijn D’hamers, FARO ; Laura De Becker, University of Michigan ; Leen Beyers, MAS Antwerpen ; Maarten Couttenier, AfricaMuseum Tervuren ; Marc Jacobs,FARO & Vrije Universiteit Brussel ; Margot Luyckfasseel, UGent ; Marnix Beyen, UAntwerpen ; Martin Vander Elst, UCL, signataire de la carte blanche « Restitution des trésors coloniaux : la Belgique est à la traîne » dans Le Soir du 25/09/2018 ; Mathieu Zana Etambala, AfricaMuseum Tervuren ; Michael Meeuwis, UGent ; Nicole Gesché-Koning, Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles ; Nicole Grégoire, ULB ; Olga Van Oost, FARO ; Olivia U. Rutazibwa, University of Portsmouth ; Pauline van der Zee,UGent ; Paul Catteeuw, FARO – Histories ; Pedro Monaville, NYU Abu Dhabi ; Philippe Van Cauteren, S.M.A.K. Gent ; Rik Pinxten,UGent ; Roel Daenen, FARO ; Marco Martiniello, Université de Liège ; Sandrine Colard-De Bock, Rutgers University ; Sarah Van Beurden, Ohio State University & UGent ; Saskia Willaert, Muziekinstrumentenmuseum Brussel – KMKG ; Sarah Demart,Université Saint-Louis, Bruxelles, signataire de la carte blanche « Restitution des trésors coloniaux : la Belgique est à la traîne » dans Le Soir du 25/09/2018 ; Sofie Van Bauwel, UGent ; Sophie Withaeckx, VUB ; Steven Van Wolputte, IARA/KULeuven ; Stijn Joye, UGent ; Véronique Clette-Gakuba, ULB, signataire de la carte blanche « Restitution des trésors coloniaux : la Belgique est à la traîne » dans Le Soir du 25/09/2018 ; Vicky Van Bockhaven, UGent.

Former Kotoko Player George Asare elected SRC President at PUG Law Faculty

Former Kotoko Player George Asare elected SRC President at PUG Law Faculty

2024 elections: Consider ‘dumsor’ when casting your votes; NPP deserves less — P...

2024 elections: Consider ‘dumsor’ when casting your votes; NPP deserves less — P...

You have no grounds to call Mahama incompetent; you’ve failed — Prof. Marfo blas...

You have no grounds to call Mahama incompetent; you’ve failed — Prof. Marfo blas...

2024 elections: NPP creates better policies for people like us; we’ll vote for B...

2024 elections: NPP creates better policies for people like us; we’ll vote for B...

Don’t exchange your life for wealth; a sparkle of fire can be your end — Gender ...

Don’t exchange your life for wealth; a sparkle of fire can be your end — Gender ...

Ghana’s newly installed Poland train reportedly involved in accident while on a ...

Ghana’s newly installed Poland train reportedly involved in accident while on a ...

Chieftaincy disputes: Government imposes 4pm to 7am curfew on Sampa township

Chieftaincy disputes: Government imposes 4pm to 7am curfew on Sampa township

Franklin Cudjoe fumes at unaccountable wasteful executive living large at the ex...

Franklin Cudjoe fumes at unaccountable wasteful executive living large at the ex...

I'll 'stoop too low' for votes; I'm never moved by your propaganda — Oquaye Jnr ...

I'll 'stoop too low' for votes; I'm never moved by your propaganda — Oquaye Jnr ...

Kumasi Thermal Plant commissioning: I pray God opens the eyes of leaders who don...

Kumasi Thermal Plant commissioning: I pray God opens the eyes of leaders who don...